In Taxi (2015), the third film Iranian director Jafar Panahi made in defiance of the 20-year ban on filmmaking imposed on him by the Tehran regime, the filmmaker drives a taxi through Tehran, picking up random passengers along the way. The film is shot with a small camera installed on the dashboard. The first passenger mistakes the camera for a car alarm; in the end, two thugs, probably secret police or maybe just ordinary criminals, break into the car and steal it. In the film, the cinema is ubiquitous. One of the passengers is Panahi’s niece. She reads to him the instructions that she was handed by her teacher for a school assignment to make a short film: “Realism, but no sordid realism”. Later, a wedding party uses the taxi to rehearse routines for a wedding video, such as getting in and out of the car. For their wedding video shoot, the couple uses their own digital camera. We know this because the dashboard camera is pointed at the viewfinder of Panahi’s niece’s camera, which records the camera outside of the car, which in turn records the wedding video routines. This mise-en-abyme of observation points simultaneously to a society in which (self-)surveillance and the spectacle of public staging of the self are omnipresent, and to a situation of ubiquitous media saturation.

One passenger recognizes Panahi not only as the well-known filmmaker that he is, but also as his client in a specific form of media exchange. It turns out that the passenger is a video dealer who earns a living delivering illegal copies of otherwise unobtainable international films—Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris (2011) and Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011) are mentioned explicitly—to the homes of wealthy customers, of which Panahi is one. 1 In hopes of bolstering his business credentials, the video dealer cheekily introduces Panahi to one of his customers as a business partner. While he deals in a rich catalogue of “world cinema” and twenty-first-century “quality television”, from Kurosawa and Kim Ki-duk to the fifth season of The Walking Dead (“Zombies are for my family”, he explains), the customer reveals that he is actually a film student in desperate need of a subject for a film. Panahi tries to offer advice, but eventually refers to reality as the only reliable source of inspiration. In a film that highlights the ultimately futile distinction between documentary and fiction, this re-affirmation of reality comes as a sudden twist, highlighting that reality cannot be thought of independently of its mediatization. Throughout the film, all of Panahi’s earlier films are either explicitly mentioned or indirectly referred to, and one passenger claims that he immediately realized that the other guests in the car (an injured victim of a car crash and a wailing woman accompanying him) were, in fact, actors. He remarks that this would also make him an actor in Panahi’s fictional universe: a universe built around a camera in the interior of a mobile car, rather than the apartment and the house of the two earlier films.

As it turns out, almost everyone in Panahi’s carefully crafted universe is concerned with making films in one way or another. The video delivery man in particular, who also offers rushes of films still in production, demonstrates how, even in a country with a comprehensive censorship regime such as Iran, the global circulation of moving images, like water, always finds a way and leaves little terrain uncovered. At the same time, Taxi illustrates how informal film production, which includes all forms of occasional digital filmmaking, has outpaced film production in the restrictive formal industry. In the end credits of Panahi’s film it is revealed that there cannot be proper credits because that would require a government permit. Because of his ban, Panahi cannot obtain a permit. There used to be a clear distinction between producers and consumers which is becoming increasingly fragile and unstable. In fact, the proliferation of “-woods”, from Hollywood and Bollywood to Nollywood and Wellywood, might similarly indicate how former hierarchies are no longer in operation.

Panahi’s production suggests film is ubiquitous, yet its presence is asymmetrically distributed between a variety of social actors and institutions. Who makes films and under what conditions? Who controls the circulation of images and controls censorship? Who watches who, where, when, and under what circumstances? And if moving images, like water, always find a way to spread, how do they affect the spaces that they reach and the interstices they use? These are some of the questions that Panahi’s film raises and that we would like to address in the present volume. The working hypothesis of this volume is that the hierarchically employed dichotomies that have long guided the study of film—for example, center/periphery (that is, the film culture of urban centers such as Paris, Berlin, and New York vs. the rest of the world), first/second and third cinema, theatrical/non-theatrical, auteur cinema/non-artistic forms and uses of cinema, professional/amateur, and also experimental avant-garde/mainstream cinema—no longer apply to the current state of moving-image culture.

By and large, the field of cinema studies has responded to the recent shifts in moving-image culture and technology by declaring that we have entered the age of “post-cinema”. The concept of post-cinema evolves around issues of medium specificity and ontology. It focuses on the two classical markers of cinema’s specificity, namely the photographic index and the dispositive of cinema, and designates a condition in which both the index and the dispositive are in crisis. While the most productive accounts of post-cinema rarely trace this filiation in an explicit fashion (Shaviro, Denson, Casetti), the label is closely related to the concept of post-media as developed by Félix Guattari in the early 1990s and later adapted for art and media theory by Rosalind Krauss, who speaks of a “post-medium condition”, by Lev Manovich, who postulates a “postmedia aesthetics”, and by Peter Weibel, who diagnoses the emergence of a “postmedia” condition. What unites these concepts and approaches, from philosophy to art history and film theory, is a tendency not just to diagnose but to mourn the loss of medium specificity, as well as to closely tie the issue to medium ontology.

However, in the debate over post-cinema, we are now rapidly approaching a point where mourning turns into melancholia. In the world of theory, cinema—the paradigmatic art form of the twentieth century and once, according to an earlier incarnation of dominant film theory, the site upon which the fate of the subject in late modern society was decided—is now living the “haunted un-life” (McCrea), like animated characters who step over the abyss, hang in the air, and fall, only to be revived and condemned to repeat the exercise in the next shot.

Taking a cue from Wittgenstein’s idea of philosophy as therapy for concepts, this volume proposes that the current state of post-cinema requires us to move on and develop new heuristic frameworks and epistemological tools that account not just for cinema as an art form and as index and dispositive, but for a multitude of (re-)configurations of film, without awarding a historical or epistemological privilege to one specific, contingent configuration known as “cinema”.

A History of Terms and Concepts

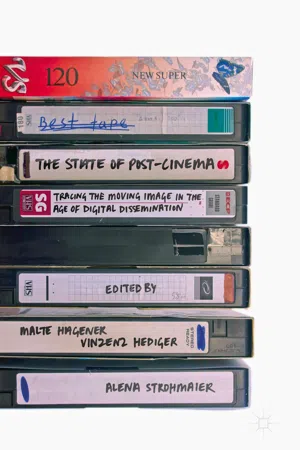

Accordingly, this book simultaneously addresses the state of post-cinema and the history of film and media studies. It proposes to extend and project this history into the future. In addressing the shared past—the canon, the established methods, the known facts and figures, but also the dead ends and forgotten objects that new methods such as media archaeology unearth—in new ways, we have to start transforming and adapting our approaches for the future. In this process, we have to grasp the present as the moment when the past’s certainties are opened up to the future’s possibilities. While this book is mostly concerned with the present, it insists on an elucidation of current transformations in light of film culture in the twentieth century. In other words, this book insists on re-framing our understanding of what film was in light of what it is now becoming. In addition to a focus on issues of historiography and epistemology, the book also takes stock of new methodologies, particularly of digital research methods, from “search as research” to digital criticism, 2 and reflects on the transformation of the film as an object of knowledge through these new methodologies.

This anthology contains a series of case studies and methodological probes that map the field for further and more differentiated research. It offers not a wholly developed research program or a coherent critique of the current state of the field; rather, the book should be read as an archipelago of interconnected operations aimed at opening up future developments and a proposed re-structuring of our discipline. Most of the essays found in this book come from the margins in one sense or another. The essays treat marginal subjects or use approaches developed at the margins of the field. One of the points of this volume is to question the validity of the hierarchies of value implied by dichotomies such as center/margin or periphery, and to question the very notion of marginality itself. In order to do so, it is necessary to revisit some of the terms and ideas that have been influential in shaping this field.

For instance, the term “third cinema”, which was first introduced by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in 1969, provided a map of world cinema for close to two decades. It created visibility for modes of filmmaking that did not fit into the categories established and recursively reinforced by Western film industries and institutions of film culture such as the film festival or the cinémathèque. Yet, as the growing prominence of globally operating film industries from Asia made clear as early as the 1970s, there is a lot more to be found in the world of film than was dreamt of in Solanas’ and Getino’s philosophy. Depending, as it was, on the affirmation of the pre-eminence of Hollywood (“first”) and European auteur (“second”) cinema, the notion of “third cinema” ultimately revealed itself to be a thoroughly Eurocentric project, designed to bring to the attention of American and European audiences a cinema that would hardly have been able to sustain itself independently of that attention.

Neither the popular cinemas of India or Southeast Asia nor the informal video film industries of Nigeria, Kenya, and other African countries fit into the taxonomy proposed by Solanas and Getino and propagated by film scholars throughout the Western world for the next three decades. As film studies matured as a discipline, it became increasingly safer to veer away from the study of the canonized masterworks of Western cinema and the works of Indian and Japanese filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujirō Ozu, who fit the European auteur paradigm, and to include other modes and traditions of filmmaking in our understanding of global film culture. As it turned out, while Hollywood films reached most parts of the world and European auteur films dominated the Western art film market, there were large parts of the global landscape where audiences preferred other modes of filmmaking for both cultural and economic reasons. These “third cinema” films spoke more directly to their concerns. Indian films were successful because they highlighted issues of post-colonial masculinity and romantic love in contrast to the traditional matrimony emphasized throughout the Muslim world. Furthermore, American films were, for the most part, only available as degraded pirated copies or in cinemas that charged much higher prices than those screening Indian or Southeast Asian films. This progressive discovery of the actual outlines of the world cinema map necessitated a critique of the established taxonomies and epistemologies of the study of cinema, and set in motion the corrosive conceptual dynamics of which the present volume purports to be a productive continuation.

Concepts such as “transnational cinema” and “world cinema” constitute useful contributions towards a re-ordering of the established taxonomies of the study of film. Yet the concept of transnational cinema, much like the concept of “intermediality” and “transmediality”, re-affirms that which it purports to transcend: “nation” as a pre-existing entity in the case of transnational cinema, and media as distinct, pre-existing entities in the case of intermediality and transmediality. “A nationalist”, writes George Orwell in his 1945 essay “Notes on Nationalism”, “is one who thinks solely, or mainly, in terms of competitive prestige”. As long as films continue to compete for awards in international festivals and success is attributed to the name of the country of origin, cinema continues to be defined in terms of competitive prestige rather than in terms more suited to a world of ever-changing and dynamic exchange processes characterized by asymmetrical and a-hierarchical power relations.

Post-colonial studies have widely engaged with those hierarchical power relations and contributed to the conceptualization of hybridized national and intercultural films, exilic, diasporic and migrant films, and haptic and feminist films. Characters, images, and narratives move across and between contingent histories and geographies, which the temporal and spatial malleability of cinema actualizes in powerfully affective ways. Post-colonial cinema might be characterized by the merging of perspectives and aesthetics and the enhancing of subaltern subjectivities and marginalized identities. The trajectories and applications which enact these overlappings might then be of various natures, charting possible (new) routes in thinking about cinema and film studies (Shohat and Stam; Ponzanesi and Waller; Weaver-Hightower and Hulme). However, as useful as this perspective has proven, it is also in danger of fortifying—and therefore inadvertently reproducing—the very structures it sets out to critique and dismantle. The very act of opposing certain power formations runs the risk of overrating their monolithic and unified nature, a fact well known from feminist film theory of the 1970s. This theory constructed overpowering straw men who were resolutely attacked, and failed to point out the c...