As everyday performers of cultural and personal identity, names have long been a concern to nation-states, which have, at times, intervened to mandate renaming in a prescribed language. The Republic of Turkey’s Surname Law of 19341 ruled that citizens adopt and register Turkish language surnames. Given two years in which to perform this task, citizens were restricted in their choices by Article Three of the law on existing or newly adopted surnames: Names with reference to foreign nationalities, races, tribes, and morally inappropriate and ugly names were prohibited. Citizens who did not voluntarily come to register a surname, would be assigned a name by the local official.

As a historical ethnography of surname legislation informed by James Scott’s notion of the modern state as an entity that seeks legibility (1998),2 my book explores this law’s genesis in the cultural nationalist imaginary, its drafting in parliamentary debates, its shaping by the Language Reform, and its release and variously mediated popular reception among citizenry. My project uses oral historical narrative, official parliamentary and previously untapped documents from registries, archival documents, and visual and written material from popular media. This book brings narrative methodology and pragmatics to bear on the various contexts in which names and surnames became created or maintained and, more specifically, how names became sites of neutralized or augmented meaning. I argue that surnames circulated in competing, parallel, and overlapping cultural economies absorbing of, opaque to, or paralleling the state-disseminated culture. Oral historical and petition statements show that while much of the reception of the law took place across context-dependent and culturally defined status relationships, there were other situations providing upward or downward mobility. Depending on the perceived and actual relationship of the interlocutors, names were taken, received, created, bestowed, translated, truncated—and even bought. Selected population registry records indicate that while many families maintained surnames that had been registered previous to the law, others came to have new surnames that either erased their background, or paralleled other local names. Petitions by, and oral historical interviews with members of Armenian and Jewish citizens show attempts to neutralize or maintain ethnic markers in names, or directives by the registry to replace ethnically or religiously marked names with a Turkish name, but there are also cases where families were able to maintain original family names. Ultimately, the Surname Law was mediated through agents who often reinforced existing patterns of authority and in circumstances that particularized the nature of the surname adoption. Beyond larger patterns, there was great variation among the experiences of surname adoption, depending on the relationship of the citizen and official to one another and to the particular geographic location.

The Surname Law is one of the last reforms undertaken by the Republican People’s Party (RPP) under Mustafa Kemal, who, under a separate law that year, acquired the surname, Atatürk,3 chief of Turks. As students of modern Turkey are well aware, the elite driven reforms were designed to transform all aspects of life, including costume and language, and to sever Turkey’s ties with an Islamic, Ottoman past. Much has been written about what the reforms intended to accomplish, and recent decades have seen a growing body of work that explores social and cultural history as well as the transnational history of the reform period.

My study enriches an emerging social and cultural history of this period marked by a focus on new sources that both challenge and complement official and political history approaches. Current approaches question previous periodization, draw from sources beyond the urban and political centers, and employ methodologies in oral history, anthropology and cultural studies to uncover and deepen understanding of the broader impact of major events that had been omitted from official historical accounts.

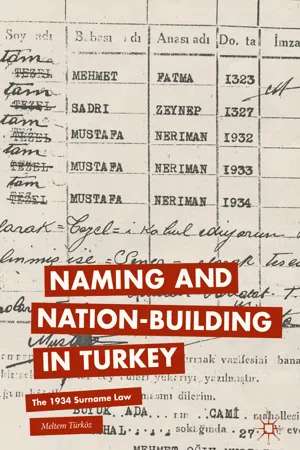

The population registry documents I accessed are typically closed and the petitions, correspondence and name lists opened up an exciting new source base and made it possible to see the “graphic artifacts” (Hull 2003, 290) of surname registration . Though set in the context of the study of modern Turkey, my book is informed by the history of surname legislation in a broader geography and places Turkey’s surname legislation in a historically comparative framework.

The Republic of Turkey, successor to the multi-ethnic Ottoman Empire , was declared in 1923, and immediately thereafter, its government led by Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) launched a series of reforms to sever the new republic’s ties with the imperial past,4 to catch up with Western sociocultural and political standards, and to consolidate a nationalized citizenry. In Turkish official sources, these reforms are known as Atatürk Inkilapları (Atatürk revolutions).5

These reforms began with the abolition of the Caliphate and the exiling of the Ottoman Dynasty in March 1924 and continued with the Hat Law,6 which replaced the fez7 and other traditional headgear with the western style hat. In 1926, the government adopted the Italian Penal Code and the Swiss Civil Code and also the Western clock and calendar.8 With the Alphabet reform in 1928, the Arabic alphabet was replaced by the Roman script,9 and the Language Reform was launched in 1931 to weed out Arabic and Persian loan words in Ottoman Turkish and replace them with rediscovered, or invented, Turkic equivalents.

The Turkish Grand National Assembly (GNA) ratified the Soyadı Kanunu (Surname Law) on June 21, 1934. The law enforced the registration of Turkish surnames and reversed traditional name sequence by stating that a surname should follow the personal name in speech and writing. More importantly, it mandated that surnames be in Turkish and be devoid of markers of religion, ethnicity, and Ottoman hierarchy. It forbade names belonging to civil officials, tribes or foreign nations, and names that were morally unsuitable or disgusting.

That fall, the GNA bestowed upon the founder of the nation, Mustafa Kemal, the surname Atatürk (chief of Turks), by which he would henceforth be known. Shortly thereafter, “The Law on the abolition of such appellations and titles as efendi, bey, and pasha” would ban all religious, military, tribal, and other honorific titles.10 The following month, the Resmi Gazete (Official Gazette) would publish the Soy Adı Nizamnamesi 11 (Surname Regulation), providing detailed guidelines for state registrars and other local officials on enforcing the law. Citizens were notified of the law via daily newspapers, the religious directorate, and through educational institutions. Newspapers, books, and registry offices made available lists of acceptable names to guide the populace in their search for a new family name.

The Surname Law is routinely included in the history of modern Turkey but has not received the same attention as the preceding reforms, even in the official perspective. In university textbooks that reflect the official history perspective, the Surname Law has received a scant description and is often presented without any comment (Ertan 2000, 256). It is likely that this is because it was received with relatively less controversy compared to other reforms of the time. With a rising interest in identity, nation-building and sociocultural history, since the 1990s it has come under increasing scrutiny. Nevertheless, it was a law which citizens complied with by lining up outside civil registries to adopt surnames, and each family’s story is unique, though patterned by proximity to urban centers, or level of geographic or social mobility, and positioning in the evolving nation-state.

Kemalist Reforms and Critical Perspectives

Scholars today do not dispute that the reforms undertaken under the new republic were top-down measures designed to transform a population from above. Reşat Kasaba and other scholars of modern Turkey compare the political elites of the early republic to the Jacobin movement, whose top down reforms from 1793 to 1794 encompassed all aspects of life, including the calendar, names, and clothing (Kasaba 1997, 30). Critiques of this period have focused on the fact that it was top-heavy, driven by a modernizing elite that imposed institutions, beliefs, and behavior on Turkey’s people (Kasaba 1997; Keyder 1987; Mardin 1997). The critical and social history12 of Turkey is informed by a broad social science base, and challenges previously held assumptions. By questioning issues such as the periodization of modern Turkey, the singularity of Mustafa Kemal as an agent of the nation, by looking beyond the political center to the provinces, by focusing on methodologies of oral history to uncover intersections of gender, ethnicity, and class, by seeking out sources beyond the center, and finally by bringing a comparative lens to Turkey’s modernization, these studies offer both correctives to, and a deep expansion on earlier studies.

Earlier approaches to the Kemalist years, informed by a unilinear model of modernization, have been criticized for minimizing social ambiguities that did not fit into narrow schemas of progress.

Most such authors regarded the breaking of traditional ties as so urgent a task that it mattered little what methods were used to achieve that end. So long as those methods were directed against institutions and practices portrayed as intrinsically antithetical to progress and modernization (meaning, in most cases, Islamic), they could be justified. (Kasaba 1997, 30)

Since the late 1980s, there has been more of an interest in the “less tangible effects of processes of social transformation … the emergence of new identities and forms of subjectivity, and…the specificities of the ‘modern’ in the Turkish context” (Kandiyoti 1997, 113).

The social historical works are united in their insistence on looking beyond the “phoenix rising” story of modern Turkey with the periodization, attributions of agency, and narrative direction that entails. Historians and historical studies of modern Turkey have moved away from previous narratives13 that saw the emergence of modern Turkey as a stark rupture and also from “the image of Turkey arising from the ashes like a phoenix” (Zürcher 1992, 237). They have focused increasingly on the continuity between the Tanzimat reforms, the Young Turk Era, and the early years of modern Turkey (Meeker 2002; Deringil 1993; Zürcher 1992; Georgeon 2000).

In discussions of the state’s control over the dissemination of Kemalism , scholars have described the population as indifferent, passive, unlike populations that participated in upholding authoritarian regimes, elsewhere in that period. In arguing that the regime of the 1930s could not be considered technically fascist, because it did not have a mass social base, Keyder maintained that it was a “regime established over a society which had not yet become a ‘people’, let alone citizens” (Keyder, 109). This description of passivity may have also been used in comparative ways, as Keyder, for instance, compares the participation of the masses in Turkey to Italy. Yet Turkish citizens of different geographic origins, of different classes were cognizant of ways they could or could not act upon their world, as more recent studies have shown.

Gavin Brockett’s work, based on provincial newspapers, focuses on “popular identification with the ‘nation’—as distinct from the articulation of nationalism as an ideology” in the first decades of the republic. Provincial newspapers were important aspects of the process of nation-building in that “they allowed people to actually participate in the ‘theater of the nation’” (Brockett 2011, 125).

A notable example of a study that examines the various ways that citizens mediated and acted in response to the major reforms is Hale Yılmaz’s Bec...