1.1 Introduction

The banking crisis from the late 1990s in Japan remains the most memorable incident in Japanese financial history. It was commensurate with the Showa Kin’yu Kyoko, the Showa financial crisis in the 1930s, following the global Great Depression that began in 1929. The banking crisis led to a restructuring of the banking industry, which had not changed for 50 years after World War II. In this chapter, first the banking crisis that occurred mainly during 2000–04 is specifically examined. Secondly, causes, bank behaviours, political reactions including monetary policy, and the results are reviewed. In this book, the financial crisis is defined as a financial turmoil that includes all financial institutions from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s. The banking crisis is defined particularly as bank failures during 1998–2004. In that sense, the banking crisis is included in the financial crisis in terms of both substance and period.

1.2 Outline of the Banking Structure in Japan

The banking structure in Japan is a hierarchical one similar to those in other nations. It was established during the Meiji period (1868–1912). The banks in Japan are classified fundamentally by their origin and business area. The city banks are in the top tier. The regional banks are in the second one. The second regional banks are in the third tier. Finally, the cooperative financial institutions are in the fourth tier. Their numbers and the deposits controlled by organizations of each classification are presented in Table

1.1. In the late 1980s city banks numbered 13, reducing to 11 by April 1996 because of mergers. These have agglomerated into five in the four financial groups after the restructuring that occurred at the beginning of the 2000s. The regional banks numbered 64 in the 1980s, the same as in 2015. The second regional banks

1 numbered 68 in the late 1980s; there were 41 in 2015. The cooperative financial institutions mainly consist of entities in four categories: the

Shin’yo Kinko (Shinkin), the

Shin’yo Kumiai (Shinkumi),

2 the

Rodo Kinko (Rokin),

3 and the

Nogyo Kyodo Kumiai (Nokyo),

4 and others. The cooperative financial institutions have been aggregated since the early half of the 1990s.

5 Table 1.1Outline of the Japanese banking industry (trillion yen)

Domestic banking account | 147 | 513.9 | 110 | 717.1 |

City banks | 12 | 227.7 | 5 | 327.0 |

Regional banks | 64 | 155.0 | 64 | 252.9 |

Second regional banks | 68 | 59.0 | 41 | 64.8 |

Long-term credit banks | 3 | 55.9 | 0 | 0 |

Shinkin | 451 | 82.6 | 267 | 132.0 |

Shinkumi | 407 | 22.4 | 154 | 19.2 |

Norinchukin banks | 1 | 25.2 | 1 | 56.8 |

Agricultural cooperatives | 3574 | 56.1 | 679 | 93.7 |

Japan Post Bank | 1 | 136.2 | 1 | 177.2 |

In addition to the private financial institutions, a few financial institutions exist under the control of the government. Japan Post Bank Co. Ltd. (Japan Post Bank) which used to be part of the public agency, the Japan Post, is undergoing privatization. Japan Finance Corporation (JFC) is an institution wholly owned by the government and providing financial support to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and individuals. Development Bank of Japan Inc. (DBJ) is in charge of supporting industries financially based on the industrial policies of the government. Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) is responsible for supporting government policies in terms of internationally financial support, mainly to enterprises.

In terms of the deposit amount, it is readily apparent that the city banks are much larger than regional banks. For example, the deposit size of the city banks, on average at present is 20 times that of the regional banks. The average size of Shinkin is much smaller than that of the regional banks, reflecting their inherent histories.

Business functions of the financial institutions have been similar in terms of financial intermediaries, but the sizes of clients and scope of operations in addition to business areas have differed depending on their place in the financial hierarchy. The three megabanks have some background as a financial centre of a particular business concern such as the Mitsui Group, the Mitsubishi Group, the Sumitomo Group, and the Fuyo Group.6 The business areas of the megabanks extend not only throughout Japan but also all over the world. Their clients vary from individuals to large listed firms including transnational firms. However, the regional banks and the cooperative financial institutions originated as local financial institutions operating in one particular district. Therefore their clients are fundamentally limited to individuals and business entities in each district.

1.3 The Bubble Economy and Its Collapse

1.3.1 The Three Causes of the Bubble Economy

The Japanese economy was highly boosted and rapidly growing in the late 1980s. It was known as ‘the bubble economy’. The causes had originated in the 1970s during the two oil shocks. In the 1970s, demands for fixed investment of private firms in Japan decreased markedly and the annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate in real terms declined from about 10 per cent in the 1960s and the early 1970s to less than half that. Then large firms had surplus funds for undefined uses. However, the government adopted an expansionary fiscal policy to inspire the economy. The bond market became larger and larger through large issues of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs). As a result, high demand for financial investments was amplified. The result resembled the disintermediation phenomenon prevailing in the US financial market in the early 1970s.

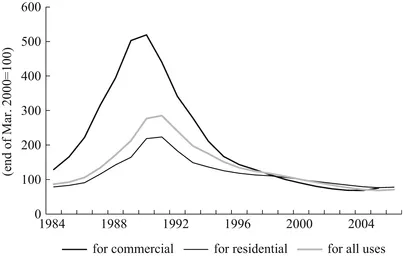

The US government under the presidency of Ronald Reagan strongly requested in the early 1980s that Japanese financial markets be deregulated and opened up to foreign financial institutions and investors. Under these circumstances, multinational firms and other large firms switched their funding sources from commercial banks to capital markets. As a result, the large banks rushed to expand mortgage loans responding to the sharp rise in real estate prices. The movement of land prices in Japan is shown in Fig.

1.1. Banks were trying to win a competition under inexperienced financial deregulation. The financial authority itself inspired them to take risks and mutually compete.

So many discussions have taken place about the causes of the Japanese bubble economy of the late 1980s. The situation can be summarized as follows, in comparison with the Subprime Loan Crisis in the USA and the banking crisis in Europe. The first cause was government economic policy. The Japanese government needed to inspire the domestic economy to increase imports because the trade surplus against the USA had become an important political issue in both countries. The G5 countries had already agreed to an alignment of the foreign exchange rates against the US dollar at the Plaza Hotel in September 1985: the so-called Plaza Accord. The Japanese government intervened in the foreign exchange market by selling the dollar in the market. The Japanese yen to US dollar exchange rate increased by 34.1 per cent from 237.10 yen at the end of August 1985 to 156.05 yen at the end of August 1986, as shown in Fig.

1.2. According to this appreciation, the purchasing power of the Japanese yen had been greatly increased.

7 To prevent the further rise of the yen, the government intervened in the foreign exchange market by buying a huge amount of US dollars by selling Japanese yen. However, the Bank of Japan (BOJ), the central bank of Japan, did not adopt a sterilization policy. As a result, a huge amount of yen remained in the money market. The liquidity held by the banks increased considerably and led to the funding of speculative investments. However, the government tax revenues increased along with asset inflation in terms of a fixed property tax and a tax on income from real estate transfers. This functioned as an incentive for the government to continue with the existing conditions.

Th...