In March 1806, the Court of Common Council met in London’s Guildhall to discuss one of the latest events in the ongoing war with Napoleonic France. At the end of the meeting, the assembled councilmen and aldermen resolved to award the freedom of the city to Admiral John Thomas Duckworth, together with a sword valued at 200 guineas, ‘as testimony of the high sense the City of London entertains of his gallant conduct’.

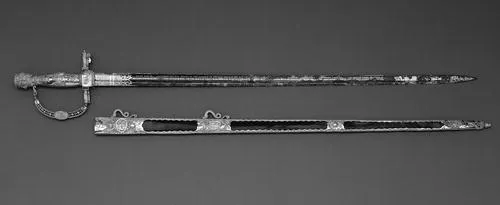

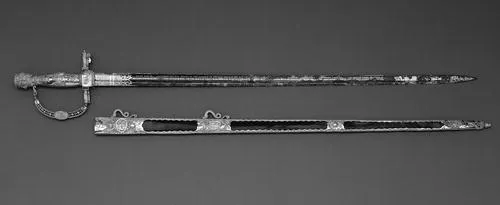

1 The presentation sword—now in the collection of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich—was made by Richard Teed, the leading sword manufacturer of the day (Fig.

1.1).

2 Duckworth’s actions, which inspired such appreciation in London, took place on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. The inscription on the beautifully damascened, straight steel blade of the sword acknowledged Duckworth’s ‘zeal and alacrity’ in pursuing a French fleet to the Caribbean and ‘more especially for the skilful and gallant attack made by him on that fleet on the 6 Feb[ruary] … off St Domingo’.

3 The incident recorded in the inscription, and recognised in the award of the sword, demonstrates the crucial role played by the Royal Navy in defending and extending Britain’s Atlantic empire. Learning that a large French raiding squadron had mobilised in Caribbean waters a single day’s sail from Jamaica, Britain’s most valuable colonial possession, Duckworth took the powerful enemy force by surprise. His successful actions during the ensuing Battle of Saint Domingo ultimately secured the British Caribbean islands and paved the way for the capture of Curaçao, Martinique, Cayenne and Guadeloupe later in the war. 4 The gift of the sword marked this out as a remarkable achievement. But Duckworth’s behaviour and its sparkling rewards were in keeping with British naval priorities during the wars with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, and the preceding century. Throughout the eighteenth century, the Royal Navy defended British interests overseas as well as at home: it ranged far and wide in Atlantic waters, defending British commercial and colonial concerns and attacking those of the enemy in times of war.

The men who made up the Common Council at the Guildhall might never have seen Jamaica, but they understood the defence of Britain’s empire in the Caribbean to be of profound importance to them in London. For British merchants and politicians alike, the coasts, islands and ports of the Atlantic—with its trading enclaves in Africa and settler colonies in the Americas—constituted an extended community with commonalities of interest and of experience, all linked together by the British (and other) ships that criss-crossed the ocean. The transatlantic colonial commerce of this British Atlantic world included the Newfoundland fisheries and export markets for British manufactures around the Atlantic littoral. But it was imports of American produce, and particularly of slave-grown plantation staples like tobacco and sugar, that made up its most important element. This activity brought luxury items to British consumers and provided tax revenues that helped to bankroll the war effort against France, including the naval protection of the British Isles themselves. Moreover, colonial trade underpinned economic activity and employment in Britain, not to mention the creation of some of the huge fortunes amassed by merchants in port cities like Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow, as well as London. Therefore, the loss of key colonial assets had the potential to cause economic hardship and financial loss throughout the British Atlantic empire, and it fell to naval officers like Duckworth and the seamen who served under them to risk or give their lives to secure, protect (and sometimes expand) these British webs of production and exchange.

However, the integration of the navy into this world of colonisation, commerce and migration went far deeper than its military responsibilities. Between 1802 and 1805, Duckworth lived in Jamaica as the admiral in charge of the naval station and dockyard at Port Royal, across the harbour from the large port town of Kingston on the island’s south coast. His main duty was to protect the colony from foreign invasion. But, as in all Caribbean plantation colonies, where the enslaved population vastly outnumbered white colonists, the force Duckworth commanded also stood poised to assist the army and local militia in case of slave uprisings. In all of these matters, the admiral on station liaised closely with the governor of the colony and was involved in a continual round of socialising: hosting fellow officers of both services on his flagship or at his country residence on the outskirts of Kingston, visiting the plantations of the powerful local slaveholders and attending balls organised by members of the local legislative assembly. When he left, in 1805, the assembly offered Duckworth their profuse thanks for his work, along with a ceremonial sword, and the merchants of Kingston presented him with a silver tea kettle, inscribed to express their respect and regard for his protection of Jamaican trade. 5 It was therefore not just London’s elite who ostentatiously demonstrated its approval of the sea officers of the British Atlantic. Whilst confronting the enemy and fighting battles in wartime were important parts of the navy’s role, this mobile and pan-imperial arm of the British state cannot be understood outside of the complicated social, cultural and political contexts in which it worked throughout the oceans and settlements of a far-flung empire.

Historiography

Historians interested in the British Atlantic world, and Britain’s eighteenth-century empire more generally, have yet to integrate a detailed view of the Royal Navy and its various roles into their work. The British Atlantic was, as Trevor Burnard notes, ‘a remarkably underinstitutionalized world’, in which government played a relatively small role in policing the movements of people and goods or controlling interactions between British colonisers, Native Americans and enslaved Africans. 6 It was, nevertheless, given its shape by Navigation Acts designed to strengthen the Royal Navy, and naval warfare and the raising of government revenues to support its huge costs were ‘at the heart of the historical processes of integrating the Atlantic World’. 7 The navy protected its sea routes of transatlantic trade and migration. Moreover, warships and their personnel were a pervasive presence in the various entrepôts, harbours and port towns that acted as nodes within this extended network, potent as both active representatives and patriotic symbols of the British state and its military power. This defining imperial institution must therefore form a key part of any analysis of the British Atlantic during the long eighteenth century.

The Atlantic world was a complex and shifting constellation of overlapping empires. However, perhaps because they have been keen to eschew approaches focused on the nation-state or on specific imperial histories, Atlantic historians have tended to focus on instances of transregional exchange, connection and creativity in ways that sometimes deemphasise the imperial frameworks that channelled or controlled them. 8 They have also tended to take a curiously land-based approach to their work, studying the ocean’s littoral regions without much direct reference to the sea or to seafarers, adopting what Hester Blum has described as ‘a landlocked critical prospect’. 9 Atlantic histories have, as Alison Games remarks, ‘rarely centred around the ocean’. 10 Historians operating within the Atlantic framework have worked extremely productively on revolutionary, counter-revolutionary, migratory and mercantile transatlantic networks, making visible a vast, variegated but integrated set of relations, which often traversed the boundaries of the European empires and other polities that spanned or bordered the ocean. 11 But few of the defining studies in Atlantic history find much to say about the navy. The most influential single volume on British Atlantic history to date, edited by David Armitage and Michael Braddick, does not contain a chapter on the military or an index reference to the Royal Navy, and subsequent overviews of Atlantic history have done little to address the lack of focus on questions of seapower and the wider roles of Britain’s navy. 12 Nevertheless, Armitage and Braddick do note that ‘warfare’ and Atlantic histories of particular institutions offer other productive avenues into the subject. 13 Jack Greene and Philip Morgan, in their more recent critical appraisal of Atlantic history, suggest that the field could benefit from studies that place ‘traditional subjects in imperial history’ within the ‘broader perspective’ provided by a transatlantic framework. 14 These useful suggestions urge a focus on the Royal Navy, which was far too integral an institution to the British Atlantic for more reasons than just its activities during wartime, for this subject to remain marginalised.

By contrast with the field of Atlantic history, the navy has been a significant point of focus in British imperial history. The Oxford History of the British Empire contains chapters devoted specifically to the themes of seapower and the navy in the period between 1500 and 1800, when the empire cohered principally around Atlantic colonies and trade. There is a historiographical chapter on the subject, along with many references to it in the other contributions to the History’s five volumes. 15 N. A. M. Rodger’s synoptic naval history of Britain also contains an analysis of the ways in which British seapower was entwined with overseas trade, including that with the colonies, as well as a discussion of aspects of naval warfare in colonial theatres of conflict during the age of the sailing navy. 16 Naval historians have made important contributions to imperial history, therefore, but until recently the history of the navy has been written ‘mainly as one of operations in wartime’, with some important work on the fiscal-military connections between the Royal Navy and the transatlantic commercial empire. 17 No major study of the Royal Navy has yet taken an Atlantic perspective on the second half of the eighteenth century. 18 Moreover, naval historians have so far been generally reluctant to connect the history of the Royal Navy with the recent work on migrations, slavery, plantation agriculture, colonial rights and trans-imperial politics that has so greatly expanded our understanding of the British empire and the Atlantic world in this period. 19 In a number of ways, therefore, Barry Gough’s observation that a sustained examination of the ‘general linkage of navy to Empire continues to escape historians’ remains valid. 20

There is huge potential to explore the linkages between the navy and the empire, as well as the importance of seapower, in our broader understanding of Atlantic history. Thanks to the work of Atlantic historians, we now have studies of various different transatlantic connections forged by groups of traders and migrants, including some studies that trace the activities of seamen within the radical networks that spanned the Atlantic during the Age of Revolution. 21 Studies of the navy promise to shed new light on such networks as well as on the characteristics of colonial societies and their often fraught relationships with distant centres of authority in the ‘mother country’. In addition, the so-called new imperial history, with its interest in the intimate links between politics, society and culture ‘at home’ in the metropole and the colonies of the wider empire, also offers tantalising possibilities for new forms of n...