eBook - ePub

Current and Emerging Trends in Cyber Operations

Policy, Strategy and Practice

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book explores current and emerging trends in policy, strategy, and practice related to cyber operations conducted by states and non-state actors. The book examines in depth the nature and dynamics of conflicts in the cyberspace, the geopolitics of cyber conflicts, defence strategy and practice, cyber intelligence and information security.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Current and Emerging Trends in Cyber Operations by Frederic Lemieux in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cyber Security. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Trends in Cyber Operations: An Introduction

Introduction

In the wake of several historical data breaches in the United States, in early 2015, the White House announced a new series of legislative proposals aimed at securing cyberspace and issued cybersecurity guidance to government agencies and the private sector (The White House 2015). Through this legislative exercise, the federal government wanted to address three priorities: (1) enable cybersecurity information sharing across private organizations and government agencies; (2) modernize law enforcement capabilities to conduct cyber investigations; and (3) establish a nation data breach reporting protocol for businesses that have experienced an intrusion during which personal information has been exposed. Through their implementation, these legislative measures will result in the deployment of both defensive and offensive strategic cyber operations by the government and private industry.

The concept of cyber operation is primarily used in the military field and refers to offensive and defensive activities related to a cyber warfare strategy. According to the US Joint Chief of Staff (2014), cyber operations include, but are not limited to, computer network attack, computer network defense, and computer network exploitation. In reality, cyber operations are conducted across multiple sectors of our society (Lin, Allhof and Abney 2014). For instance, the private-sector finance, telecommunication, and retail industries conduct defensive cyber operations on a daily basis to prevent data breaches or denial of service attacks. Several organizations in the private sector may also perform offensive cyber operations in the form of industrial espionage and competitive intelligence activities (Lin, Allhof and Abney 2014). In the public sector, government agencies including law enforcement, intelligence, and other critical departments conduct both of the aforementioned types of cyber operations by spying on domestic or foreign targets (Schmidt 2014) as well as investigate cyber offenders or provide assistance in protecting critical infrastructure by implementing the Computer Emergency Readiness Team (CERT), for example (Bada, Creese, Goldsmith and Phillips 2014).

In academia, cyber operation is considered a multidisciplinary concept intersecting mostly with the social sciences, behavioral sciences, political sciences, engineering, and law (Shakarian, Shakarian and Ruef 2013). For instance, social scientists study cyber operations from the criminology perspective, conducting cyber criminal investigation and examining illegal activities that occur in cyberspace, such as fraud and identity theft (Stephenson and Gilbert 2013). Behavioral scientists are working to find solutions to network vulnerability by studying human behaviors and developing adaptive cyber operations through biomimetics, for example (Pino, Kott and Shevenell 2014). Political scientists scrutinize current and emerging policy related to cyber operations and examine how state and non-state actors conduct cyber operations and exercise influence on international relations (Erickson and Giacomello 2007). Engineers research and develop new technologies and enhance existing tools that enable the conduct of defensive and offensive cyber operations (Bodeau and Grobart 2011). Lawyers study the evolution of laws related to cyber security and advise lawmakers on new legislation that will regulate cyber operations (Schmitt 2013). Indeed, these academic disciplines interact with each other and shape the way cyber operations are conducted.

Another critical characteristic of the cyber operation concept is its nature, which is both strategic and tactical (Andress and Winterfeld 2011). Tactical cyber operations involve techniques and practices used by information technology professionals to secure or penetrate a computer network. Tactical cyber operations can also be performed by offenders who crack, hack, and breach an information system. Strategic cyber operations build on the approaches that align with the defensive and offensive dimensions. For instance, defensive strategic cyber operations are planned and carried out based on the goals of prevention and deterrence. Offensive strategic operations are usually developed based on more hostile goals. For the purpose of this book, a cyber operation is defined as having a set of comprehensive cyber operational goals that are carefully designed and planned to serve a long-term offensive or defensive purpose. Strategic cyber operations can take the form of policy, strategy, and best practices related to computer network attack, computer network defense, and cyber security incident management.

This introductory chapter is divided into four sections. The first section examines global trends of cyber operations and focuses on current as well as emerging threats in cyberspace. The second section offers an analytical perspective on the intensity of cyber operations and the type of actors evolving in cyberspace. The third section outlines the emerging and most pressing challenges in cyberspace. Finally, the fourth section introduces the structure of the book.

Global trends in cyber operations

Recently, an article in Time magazine (Rayman 2014) listed five hotspots in the world for cyber crime and cyber operations: Russia, China, Brazil, Nigeria, and Vietnam. According to the magazine, each hotspot has its particular expertise in terms of criminal capabilities. For instance, Russian cyber criminals are known for being highly skilled in hacking and breaching data systems primarily for profit (mostly for organized crime interests). Conversely, in China, most hackers are not working for organized crime but are operating under the guidance of the government. Chinese hackers are often involved in economic and politic espionage operations. Hackers in Brazil seem to follow the path of their Russian counterparts and have been involved in large-scale money theft and fraud through payment systems as well as by targeting individuals. Cyber criminals from Nigeria are well known for email scams and hacking tactics to extort money from their victims. Finally, the situation in Vietnam presents a hybrid form of what can be found in China and Russia. While a vast number of Vietnamese cyber criminals are involved in data breaches and theft of personal information from Europe and United States, they are also deeply involved in spying operations on neighboring countries and their own citizens for the benefit of the Vietnamese government.

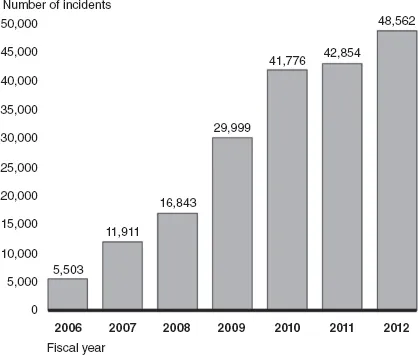

Several countries have experienced an intensification of cyber attacks in recent years. According to the Government Accountability Office (2013), the United States, one of the most targeted countries in the world, has faced a staggering increase of reported attacks on US federal agencies ranging from 5,503 in 2006 to 48,562 in 2012 (see Figure 1.1). Global trends of malicious cyber operations are tracked annually by anti-virus corporations such as McAfee, Symantec, and Kaspersky Lab. Each year, these organizations publish cyber threat assessments and provide statistics related to several types of attacks, targets, and modus operandi. According to Symantec’s Internet Security Threat Assessment Report (Symantec 2014), 2013 was characterized as the worst year on record for large-scale data breaches. The report also describes several additional important trends. Targeted attacks are on the rise, and the odds of government agencies and manufacturing being targeted is high (the odds are 1/3.1 and 1/3.2 respectively). Mobile capabilities are now plagued by social media scams and malware. According to Symantec’s report, cyber criminals have victimized 38 percent of mobile users. Ransomware attacks have increased by 500 percent, and hackers are now moving toward evolved methods called ransomscrypt. Lastly, attackers are now looking at a new field of operation and have started to hack common electronic devices that are part of the ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT), such as baby monitors, security cameras, and routers.

Figure 1.1Numbers of attacks on US federal agencies between 2006 and 2012

Source: GAO analysis of US-CERT data for fiscal years 2006–2012

In its threat prediction for 2014, MacAfee highlights a few more growing trends that posed concerns for governments and industries. The deployment of corporate applications in ‘the cloud’ will generate new attacks and unsuspected entry points. McAfee estimates that 80 percent of business users are operating applications in the cloud without informing their own corporate IT. Attacks through social media platforms will increase and become more sophisticated using features like location to target victims. According to McAfee, the Pony botnet was responsible for stealing millions of passwords from users on Facebook, Google, Yahoo, and others. The high prevalence of false or fake profiles on social media provides an indication of the capacity of social attackers. Facebook admitted that 50–100 million accounts are duplicates, and a recent survey conducted by Stratecast (2013) indicates that 22 percent of social media users have experienced security issues.

Both private sector and government reports on cyber attacks indicate that attacks motivated by cyber criminals (for profit) and hacktivists are at the top of the list. Also, reports from the anti-virus industry reveal that government agencies, manufacturing, and finance sectors are at the most risk of experiencing attacks. In terms of attack types, defacement, distributed denial of services, SQL injections, and account hijacking were the most frequent malicious attacks between 2012 and 2014. Finally, according to Ponemon Institute (2014) the average cost of a data breach occurring in the United States in 2013 was estimated at $5.4 million. In 2014, the average annual cost of cyber attacks was estimated at $12.7 million, according to a survey of 59 large US firms, indicating a 96 percent cost increase compared to the past five years (Ponemon Institute 2014).

However, while the assessments provided by anti-virus corporations are very detailed and based on millions of attack sensors deployed around the world (up to 157 countries), they don’t necessarily expose all malicious cyber operations taking place in cyberspace. For instance, the information leaked by Edward Snowden informed the public about activities conducted by the National Security Agency over several years. None of the anti-virus corporations detected the intrusions committed by the NSA in the US communication system nor the intrusions into foreign government information systems. Despite the fact that the American government can justify these intrusions under national security pretexts, many countries targeted by the NSA’s programs admitted that there were real economic and political costs to these spying activities. The lack of reporting and perhaps the selected reporting of malicious cyber operations raise the question of ethics in cyberspace and will be addressed further in this chapter.

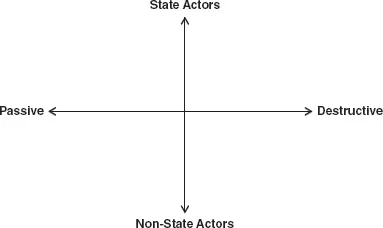

Cyber operations: intensity spectrum and actors involved

This section places an emphasis on offensive cyber operations and provides a theoretical approach to categorize the level of intensity of the operations as well as the type of actors that engineer them. Four levels of intensity can be identified, ranging from the least to the most aggressive action against actors. The first level, passive, is the least hostile type of cyber operation and can be associated with cyber espionage or reconnaissance activities aimed at gathering information for competitive purposes, for example between state actors or corporations (Hunker 2010a). In this scenario, states and non-state actors will spy or stalk their target in order to collect critical information that can benefit them. In this particular case, the spy or stalker does not want to be discovered, and its activity will exclusively remain stealth to avoid any potential exposure.

The second level, provocative, is more hostile than the previous one in the sense that state and non-state actors will use cyberspace to communicate a message or disclose embarrassing information in order to influence or polarize public opinion. On the one hand, individuals such as Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning, and Edward Snowden leaked a tremendous amount of government information with the objective of publicly embarrassing a state on actions they judged unacceptable. On the other hand, violent groups like the Islamic State (ISIS) will use cyberspace to deliver threatening messages or communicate appeals to recruit new members (propaganda). Finally the case of Sony appears to fall under this category due to the leaking of embarrassing emails and information about its employees and artists in order to intimidate the company regarding the non-release of a satirical movie about the assassination of the North Korean leader (blackmailing). In this category, provocative operations use information or messaging against their target in a public manner in order to provoke a reaction.

The third level, disruptive, refers to the perpetration of hostile actions to overwhelm and momentarily paralyze a target. Well-known examples of such hostile operations are the stealing of mass personal information, distributed denial of services (DDoS) attacks, and denial of services (DoS) attacks (Hunker 2010a). These disruptive actions generally aim at directly impacting the day-to-day activities of a target by paralyzing information systems, supply chains, and communication channels. These attacks often overwhelm the victim in its capacity to respond and mitigate the consequences of the disruption. For example, before employing traditional warfare operations, Russia is accused of using DDoS against servers in Estonia and Georgia, thereby paralyzing critical systems, such as government websites, the financial sector, and telecommunications. These Russian cyber operations disrupted the ability of Estonia and Georgia to foresee and respond to traditional military aggression by overwhelming the respective governments’ major infrastructures, undermining governmental authority prior to the use of kinetic military force (Applegate 2012). In the cases of Home Depot and Target, the stealing of mass credit-card information by hackers led to a prominent slowdown in business, forcing the credit-card issuers to reduce the purchase limit of cardholders and replace all compromised credit cards. In both cases, criminal groups are suspected to have committed the breach and stolen the consumer credit-card information.

Figure 1.2Levels of offensive cyber operations and types of actors involved

Finally, the fourth level, destructive, refers to cyber operations that aim at provoking physical destruction of computer systems or any system operating with coded signals over communication channels. These attacks can potentially cause harm to human beings, especially if targeting critical infrastructures (Lin 2010). The most sophisticated example of a destructive cyber operation is the Stuxnet virus, which was used to physically destroy several centrifuges serving to enrich uranium at Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility. This destructive cyber operation disclosed how vulnerable critical infrastructure can be if a virus or malware enters a supervisory control and data acquisition system (SCADA), causing large-scale damage.

Cyberspace is composed of a myriad of actors conducting offensive and defensive cyber operations. They can be categorized in two major groups: state and non-state actors (Valeriano and Maness 2014). The level of social organization will differ in each group (see Table 1.1). For instance, non-state actors could be a sole individual who can decide to attack a target because of the challenge it represents, for vengeance, or simply because of greed (fraud). Non-state actors can also be composed of more complex social organizations, such as violent groups or a collective of hacktivists that will attack a target for a moral or political cause. Also, non-state actors can be corporations that decide to conduct offensive operations against competitors or a government agency to steal information critical to the conduct of their business.

Table 1.1Types of cyber actors according to their level of social organization

| Non-State Actors | State Actors | |

| Low Social Organization | Individual hackers and crackers | Proxy state actors, such as cyber mercenaries |

| High Social Organization | Corporations, organized crime, terrorist groups | Government agencies and multi-governmental organizations |

The second group, state actors, also varies in its comp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. Trends in Cyber Operations: An Introduction

- Section I: Conflicts in Cyberspace

- Section II: Geopolitics of Conflicts in Cyberspace

- Section III: Defense Strategies and Practices

- Section IV: Cyber Intelligence and Information Security

- References

- Index