- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Global Automobile Demand is a two-volume work analysing the impact of the Great Recession and the structural factors which shape automobile demand in developed and emerging countries. The first volume of Global Automobile Demand examines the automobile demand in mature economies: the USA, the UK, France, Germany, Spain, Japan and Korea.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The US Automobile Market after the “Great Recession”: Back to Business as Usual or Birth of a New Industry?

Bruno Jetin

1 Introduction

Between December 2007 and June 2009, the US economy was hit by the “Great Recession”, the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. As a consequence, the US automobile industry has gone through a crisis of unrivalled magnitude: during the recession, light-vehicle sales lost 6 million units and two of the “Big Three” automakers – GM and Chrysler – went bankrupt. Since then, the US economy has recovered progressively and the automobile market is bouncing back to its pre-recession level. In fact, the automobile industry has better recovered than the rest of the economy, the growth of which is weak and uncertain. GM and Chrysler emerged from bankruptcy as new slimmed-down companies with fewer brands, plants and workers, and less debt and market share. The rejuvenated Big Three returned to profit in 2009 (Ford) or 2010 (GM and Chrysler) when the US market was still below 12 million vehicles sales a year. These companies are making bigger profits now that the market is expanding again and are on the way to reaching 16 million units in the near future. GM and Chrysler have repaid their loans and have gone public again, a move that has given the US government a way to sell part of its stake in the companies’ stock.

These events may suggest that the crisis is over and that the US automobile industry is back to the pattern that prevailed before the Great Recession. This chapter will show that there is more to this situation than meets the eye. There are short-term factors that are indeed acting positively for the automobile market. But in the medium- to long-term, the structural problems that have led the US economy to the crisis have not been resolved and will weigh heavily again. First, although the US economy is recovering slowly, unemployment levels are still high, unlike after previous recessions. A new jobless recovery seems to be underway, as after the dotcom bubble burst in 2001. Family income has dropped, poverty has risen and inequality has worsened. Second, structural factors such as the slower growth of the number of licensed drivers and a change in consumer expenditures due to growing costs of education, health and accommodation is negatively affecting car demand. In this context, the rebound of the automobile market is no doubt fragile. The temptation is strong to go back to the traditional recipe of household indebtedness to stimulate car demand. Banks, captive finance automobile companies and independent finance companies have loosened their credit standards and are originating loans actively. The subprime automobile credit market is back, thanks to the revival of asset-backed securities market that played such a critical role in the build-up of the Great Recession. The danger is the return of the dependency of the automobile market on bad loans to increase sales.

This chapter will analyse these contradictory tendencies. The first part comes back to the analysis of the Great Recession to see how much it was the consequence of an unsustainable growth regime, whereby a decreasing labour income share, coupled with growing social inequalities, have led US households to take on even more debt to maintain their consumption pattern. This growth regime has modelled car demand and car financing in a way that parallels the housing market. In a second part, we analyse the rebound of the automobile market to see why there are many reasons to think that it will be short-lived. The fundamental reason is that the US growth regime has not changed. Other important reasons are more structural: the changing demographics, consumption pattern, gas prices, and the absence of breakthrough innovation in alternative fuel cars likely to reduce dramatically the cost of motoring when it is most needed.

2 A debt-driven growth regime paved the way to the Great Recession

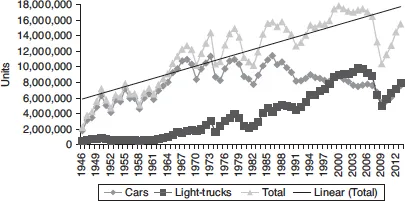

The automobile industry usually follows the fluctuations of growth cycles. In the United States new vehicle sales have been especially buoyant during the growth cycles 1961–1969, 1982–1990 and most particularly in the cycle of the so-called new economy 1992–2000 (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 New cars and light-trucks sales in the United States (1946–2013)

Source: Computed by M. Freyssenet with data from WMVD, Automotive News 100Y, GERPISA & CCFA, (1946–2007) updated by B. Jetin with data from BEA.

The automobile industry decoupled from growth at the time of the “feeble recovery” of 2001–2007 (Bivens and John, 2008) which followed the dot.com bubble burst (March 2000–June 2003)1 The gross domestic product (GDP) and employment growth were at the time the weakest since 1949, but new vehicle sales stayed at a high level, above 16 million units (see Figure 1.1). Sport and utility vehicle (SUV) sales topped at almost 10 million units while they are usually more expensive than passenger cars. With 17.4 million units in 2005, vehicle sales were not far from the historical record of 17.8 million of 2000, when the “new economy” reached its apex. There was obviously something wrong in the boom of the automobile market during the growth cycle 2001–2007 that cannot only be explained by the fall of the interest rate to zero after the 11 September 2001 attacks, which revived the economy. Nor can the Great Recession, which was triggered by the “subprime crisis”, explain the fall of the automobile market. The Great Recession officially began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009, but vehicle sales had started to decrease in 2005.

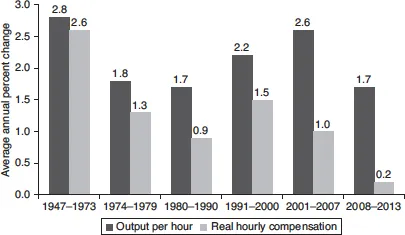

The origin of this disconnection is to be found in the structural changes of the US growth pattern introduced by supply-side economics, launched by Ronald Reagan in 1980. Since then, the percentage gap between labour productivity and real compensation has widened (see Figure 1.2).

The gap was closed to zero between 1947 and 1973 (0.2%). It almost doubled in the 1980s (0.8%) compared to the 1970s (0.5%). It narrowed a little bit during the growth cycle of the 1990s (0.7%). But during the “feeble recovery” of the years 2001–2007, it more than doubled again (1.6%), and after the Great Recession, the gap stayed at the same level. In the long term, this means that American households did not benefit as much as they could have in real compensation. In particular, since the Great Recession, real compensation remained flat, while companies were profiting much more from productivity gains. Besides, the income distribution got more and more unequal.

Figure 1.2 Labour productivity and real compensation gap in the US (1947–2013) non-farm sector

Source: Author’s calculation with data from the Bureau of Labor statistics, extracted on 2 October 2014.

Data on income concentration going back to 1913 show that the top 1% of wage earners now hold 23% of total income, the highest inequality level in any year on record, bar one: 1928. In the last few years alone, $400 billion of pre-tax income flowed from the bottom 95% of earners to the top 5%, a loss of $3,660 per household on average in the bottom 95% (Lawrence et al., 2008).

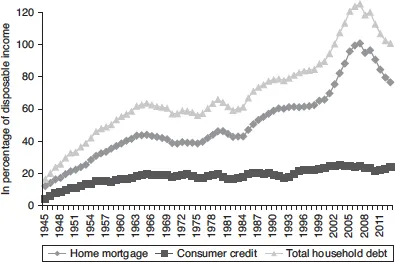

This phenomenon has not immediately affected households’ consumption for two reasons. First, households have swapped income increase with debt increase to maintain their standard of living and acquire their homes. This was made possible by the strong support of the State and the adoption of various laws by Congress. The standardisation of mortgages and the introduction of mortgage-backed securities took shape in the 1960s. Later, a decisive step was taken with the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which phased out the deductibility of most non-mortgage interest for instance interest on consumer loans. “This led to a shift of consumer debt towards mortgages and home equity lines” (Stango, 1999). Homeownership became the foundation of a stable middle class, and house mortgages became the cornerstone of household debt.2 As a consequence, household debt as a percentage of disposal income, which was stable at around 60% since 1965, started to grow rapidly to almost 100% in 2000 at the end of the new economy bubble growth (see Figure 1.3).

The bursting of the dot.com bubble in 2000–2001 had the well-known effect of shifting the focus of speculation from shares to housing. There was a new wave of finance investment (was investment) in housing construction and home mortgages, and house prices soared. Despite the success of the “jobless recovery” (2001–2007), indebtedness skyrocketed to more than 120% in 2007.

As a consequence, with the exception of recession periods, consumption has constantly increased at a higher pace than compensation. Increasing debts filled the gap to the point that the US at the time could be said to have had “a debt-driven growth regime”. Three special features of financial innovation in a context of low-interest rates and rising house prices explain why debt not only financed ordinary consumption but also created a consumption boom. In sum, these innovations contribute to explaining why, during the feeble recovery preceding the Great Recession, vehicles sales boomed, averaging 17.2 million units above the 16-million landmark achieved in the 1980s and 1990s.

Figure 1.3 US households’ debt as share of disposable income (1945–2013)

Source: Author’s calculations with data from US Flow of Funds Accounts (Fed) and NIPA (BEA).

First, the upward trend in housing prices generated a house wealth effect much more significant than the stock market wealth effect.3 An enormous wave of refinancing existing mortgages, during 2000–2006, allowed homeowners to extract some of the built-up equity in their homes. Part was used to pay down more expensive non-tax deductible consumer debt or to make purchases that would otherwise have been financed by more expensive and less tax-favoured credit. In this sense, the refinancing phenomenon was a supportive factor for growth, as long as homeowners were able to make their monthly payments. Daniel Cooper (2010, p. 1) shows that “during the height of the house-priced boom (the years 2003–2005), a one-dollar increase in equity extraction led to 14 cents higher household expenditures”. Overall, the increase was broadly concentrated in transportation-related expenses, food, schooling, and non-major home upkeep.

There is a positive and strong relationship between equity extraction and automobile costs, which include down payments for loans and leases. Equity extraction and health care costs had a smaller positive effect, which is consistent with the idea that households used equity extraction to help fund big-ticket expenditures. The problem with this financial extraction is that when house prices began to decline in 2006, it contributed to higher defaults. According to Mian and Sufi (2009), it accounted for 34% of new defaults from 2006 to 2008. In another paper, these authors show that the rise of households’ debt-to-income ratio, and the growing dependence on credit card borrowing during the years before the recession, explain a large portion of the crisis and its effect on durable consumption. In particular, they show that “counties that experienced the largest increase in their debt-to-income ratio from 2002 to 2006, saw a severe contraction in auto sales very early in the downturn and a higher increase in unemployment” (2010, p. 95). By contrast, in low-leveraged counties, auto sales were up in the first quarter of 2008 and dropped only in the third quarter of 2008 when the crisis affected the whole country.

Second, financial innovations combined with the house price boom allowed households to take more debt secured on the value of their house. A secure loan is a loan for which the lender receives collateral in return. Mortgages and car loans are among the most common secured loans. In these cases, collateral is provided to the lending institution in the form of a lien on the title to the property until the loan is paid off in full. If the borrower defaults on the loan, the lender retains the right to repossess the property (Ruben, 2009). Low-interest rates, appreciation in housing values, and the deductibility of interest payments on mortgage debt have indu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 The US Automobile Market after the Great Recession: Back to Business as Usual or Birth of a New Industry?

- 2 A Model to Follow? The Impact of Neoliberal Policies on the British Automobile Market and Industry

- 3 Excess Capacity Viewed as Excess Quality The Case of French Car Manufacturing

- 4 Income Polarisation, Rising Mobility Costs and Green Transport: Contradictory Developments in Germanys Automotive Market

- 5 The Automobile Demand in Spain

- 6 Japans Automobile Market in Troubled Times

- 7 From Expansion to Mature: Turning Point of the Korean Automotive Market

- Conclusion

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Global Automobile Demand by Bruno Jetin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Automobile Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.