![]()

PART I

Foundations

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Behavioral Approach versus Neoclassical Finance

This chapter confronts the main foundations of the neoclassical theory of finance with allegations of the behavioral approach. Theoretical models of classical financial economics do not take into account the possibility of decision maker irrationality. It is often assumed that irrational investors are not coordinated and therefore their behavior cancels out. And even if irrationality becomes strong and common among a large group of investors, it will be voided by rational actions of arbitrageurs. However, behavioral finance points out limits to arbitrage. It is argued that irrationality of investors may indeed influence asset pricing. This position challenges the main theoretical foundations of the neoclassical paradigm, including the Markowitz’s portfolio theory, traditional asset pricing models, and the Efficient Market Hypothesis. The behavioral approach is of high importance also for the second side of capital market, that is issuers. A discussion on key elements of corporate finance policy in the light of behavioral implications concludes the first chapter.

1. Decision-Maker Rationality and the Expected Utility Theory

One of the key concepts in the neoclassical theory of finance is decision-maker rationality. A rational person correctly interprets the information he receives and knows how to estimate the probability of future events on its basis. He prioritizes various alternatives according to his own utility function and tries to optimize subjective expected utility. It is assumed that rational market participants are so strong and dominant as a group that they are able to quickly and efficiently eliminate any symptoms of irrationality on the part of other traders. As a result, the market will behave as if all participants acted rationally.

Determining decision-maker preferences and the way in which he assesses investment options is a point of departure for any traditional capital asset-pricing model. In the classical approach, these issues were comprehensively described by the expected utility hypothesis commonly believed to have been put forward by John von Neumann and Oscar Morgenstern (1944) although it could be traced as far back as the eighteenth-century writings of Daniel Bernoulli (1954).

According to the neoclassical theory of finance, a rational decision maker follows two general rules. First, he displays so-called risk aversion in that he is willing to take risk only when it may lead to further benefits, that is, only when he stands a chance of being rewarded with a risk premium (Friedman and Savage, 1948). Risk aversion is a general and common phenomenon even though its degree may vary for each individual decision maker. Second, decision makers always make choices in such a way as to maximize total expected utility, given that the marginal utility of each additional benefit unit is positive.

The behavioral approach challenges both these assumptions on the grounds that risk aversion depends primarily on the context in which decisions are made. Moreover, decision makers attach greater importance to changes in the affluence level when measured against a specific reference point rather than its total value. Many behavioral experiments showed that subjects display risk aversion when they make choices between alternatives leading to lower or higher gains. However, when faced with a decision problem in the domain of losses, they are more prone to take risks. All of these observations lay at the foundation of the prospect theory developed by Kahneman and Tversky (1979).

Von Neumann and Morgenstern (1944) formalized the classical theorem on the existence of the utility function on the basis of a series of assumptions determining preferences of rational decision makers. What follows is a discussion of four fundamental axioms that cause the most controversy among representatives of behavioral finance.

1.1. Axiom of Completeness

The axiom of completeness assumes that a rational decision maker knows how to compare different options and has well-defined preferences. Comparing available information and guided by the constant set of preferences, he either prefers variant A to B, or B to A, or is indifferent between A and B.

However, Tversky and Kahneman (1981, 1986) point to results of experimental studies showing that people are often not able to correctly interpret the problems they face. Because of their limited perception of information, they are not always in a position to recognize repeated decision problems even if they are logically the same, but formulated in a different way. Depending on how the information is framed, decisions makers may exhibit different preferences in the same situations. We focus on mistakes in perception and information processing in greater detail in chapter 2.

1.2. Axiom of Transitivity

According to the axiom of transitivity, if a decision maker prefers variant A to B and rates variant B higher than C, then he will also prefer variant A to C. Even though this rule seems obvious, at least at first glance, it is also undermined by representatives of behavioral finance. The argument goes that, under real-life economic conditions, decision makers may make intransitive choices because they are motivated by several criteria of variant assessment. For example, depending on the situation in which a decision needs to be made, a decision maker may be motivated by the amount of the reward in one case but the probability of success in another.

Tversky (1969) conducted an experiment where a group of subjects were to choose from several pairs of lotteries, but the expected value of each lottery within a pair was equal. In some games the potential payoff was large but with small probability assigned. In others, the payoff was small, but the probability of winning was very high. Tversky noted that when two lotteries are relatively similar in terms of gain probability (e.g., winning is possible, but very unlikely), decision makers will choose the game offering a higher payoff disregarding the risk criterion. However, when the difference in gain probability between each of the lotteries is considerable (e.g., winning is probable in both cases, but the probability is much higher in one of them), people will choose the lottery that offers higher chances of winning, paying less attention to the actual amount to be won.

So let us imagine three possible investments, I1, I2, I3, each of which has a different expected return, E(R), and different risk level measured by variance V. Let us also assume the following relations between the expected return and risk of individual investments:

and

If the decision maker believes that differences between risk levels V1 and V2 as well as between V2 and V3 are relatively small, he will be motivated by the criterion of higher expected return when comparing investments in such pairs. Consequently, he will prefer investment I1 to I2 and I2 to I3. According to the axiom of transitivity, the investor should also prefer investment I1 to I3. This does not necessarily have to be the case. The difference between risk levels V1 and V3 may be assessed by the investor as much larger than the difference in the level of risk for the two other pairs of investments. In such a case, the investor may make decisions following the criterion of risk reduction instead of trying to maximize the expected return. He will then prefer investment V3 to V1 which is plainly against the rule of transitivity.

1.3. Axiom of Continuity

The axiom of continuity says that the choice between two variants should only depend upon differences between them or conditions under which the two variants lead to different results. If both options are changed in the same way, decision maker’s preferences should remain as they were. Hence, in accordance with the axiom, the investor should not change his mind if, for example, the risk level is changed for both variants in the same way (i.e., when the probability of each variant taking place will equally increase or decrease). However, psychological experiments have shown that people do modify their behavior in response to the level of risk. This has to do with the so-called certainty effect—decision makers tend to overestimate the value of a lottery where the reward is certain compared to a lottery with a higher expected reward but involving even a marginal level of risk (Allais, 1953; Kahneman and Tversky, 1979, 1984; Tversky and Kahneman, 1986).

Let us consider the following example. A decision maker is faced with a choice between the following investment strategies: strategy A offers certain income in the amount X, strategy B offers a possibility to earn a much higher income Y with the probability determined in such a way that the expected value of the strategy exceeds the value of income X, albeit only slightly. It turns out that in such situations decision makers usually choose strategy A, even though its value of expected reward is slightly lower. Let us now imagine that both strategies are changed in the same way, that is, they are burdened with identical additional risk, for instance, by reducing the probability of profit in each of them fourfold. Following the change, none of the strategies offers a 100 percent certainty of income. Faced with this choice, the decision maker will change his preferences choosing strategy B as the one that offers higher expected value. Naturally, the change in investor preferences contradicts the axiom of continuity.

Another aspect putting the axiom into question is the issue of sensitivity to the way in which a decision problem is presented. In other words, dependence on information framing. Kahneman and Tversky (1984) give the example of choosing a strategy to fight an epidemic involving the total of 600 people infected. The choice to be made is between two alternative treatment programs:

• program A that gives a 100 percent certainty of saving 200 of the infected, and

• program B that gives a one-third probability of saving all 600 infected people and a two-thirds probability of failing to save a single person.

Most respondents (72%) decided to opt for program A. Then, the same respondents had to choose between “other” possible programs:

• program C that will cause the death of 400 of the infected, and

• program D that gives a one-third probability that no one will die, but a two-thirds probability that all 600 people will perish.

In the second task, most of the respondents (78%) preferred program D. However, logically speaking, programs A and C as well as B and D are identical, the only difference being that the results of each of them are presented first in the context of the number of people saved, and then in the context of people who will have to die.

1.4. Axiom of Independence

According to the axiom of independence, if the decision maker treats two options X and Y indifferently, he should also be indifferent about the following two variants for any option Z:

(a) option X with probability p and option Z with probability (1 – p),

(b) option Y with probability p and option Z with probability (1 – p).

It is enough to take the example of complementary goods to show that this assumption will not always work in reality. The reason is that if any option Z turns out to be complementary in relation to X but not Y, the decision maker may be more inclined to prefer the simultaneous occurrence of X and Z to Y and Z, even though he would be indifferent toward X and Y if he considered them separately.

Considering the axiom of independence in the context of the stock market, let us imagine two assets X and Y with exactly the same amount of risk and the same expected return. Theoretically, when assessed individually, they will be perceived by the investor as equally good investment opportunities if he adopts the criterion of risk premium only. It may, however, happen that the return for asset Y will be strongly correlated with the return for asset Z while fluctuations in the value of asset X will be relatively independent of changes in the value of Z. According to classical portfolio theory, in such a case, the investor will prefer to simultaneously invest in X and Z rather than Y and Z because the first option leads to more benefits from diversification. Thus, the axiom of independence falls before it is even necessary to remove the assumption of decision-maker rationality.

1.5. Probability Assessment

According to the traditional theory of finance, before decision makers can rationally apply the criterion of maximizing expected utility when making decisions under risk, they must first estimate the probability of different scenarios and then correctly modify their beliefs in the light of new information. Theoretically, such verification of probability should be done according to Bayes’s rule.1

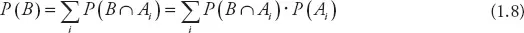

Probability of event A given the occurrence of observation B may be defined in the following way:

where:

P(A | B) is conditional probability of event A given B,

P(A ∩ B) is joint probability of events A and B,

P(B) is probability of event B.

As the probability of the product of events A and B is hard to estimate, we need to make several transformations. Conditional probability of event B given A, that is, P(B | A) amounts to:

Transforming equation (1.4) we arrive at:

Let us note that P(A∩B) = P(B∩A) and so

Plugging in equation (1.6) to equation (1.3), we arrive at the best-known, so-called simplified version of Bayes’s rule

The most important advantage of this transformation is that, unlike equation (1.3), equation (1.7) refers directly to information that is theoretically either available to the decision maker or pose no problems when it comes to assessing it.

Extended Bayes’s rule shows how to calculate the value of P(B). The denominator in equation (1.7) is a normalizing constant that can be derived from the total probability formula with the use of the marginalization principle:

We can now write Bayes’s rule in its full version, that is:

Bayes’s rule is a mathematical tool describing how rational investors should modify their opinions in the light of new facts.

Proponents of behavioral finance provide many arguments proving that investors struggle to correctly estimate probability, finding it especially difficult to apply Bayes’s rule properly. People overreact to powerful information of a descriptive nature downplaying the importance of underlying statistical data.

Kahneman and Tversky (1982) devised the following task: A taxicab was involved in a hit-and-run accident in a certain city. There are two cab companies operating in the city—one has on...