eBook - ePub

Development Cooperation

Challenges of the New Aid Architecture

S. Klingebiel

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Development Cooperation

Challenges of the New Aid Architecture

S. Klingebiel

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The aims of and motives for development cooperation have changed significantly in recent times. Besides pursuing short- and longer-term objectives in their own economic, foreign policy and other interests, donors usually have a recognisable and genuine interest in assisting countries in their processes of development.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Development Cooperation an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Development Cooperation by S. Klingebiel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Studi sullo sviluppo globale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Scienze socialiSubtopic

Studi sullo sviluppo globale1

What Is Development Cooperation?

Abstract: Development cooperation is a comparatively new concept in international relations, having risen in importance only after the Second World War. The aims of and motives for development cooperation have since changed significantly. Besides pursuing short- and longer-term objectives in their own economic, foreign policy and other interests, donors usually have a recognisable and genuine interest in assisting countries in their processes of development. In the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the international community has an acknowledged frame of reference for global objectives, which play a major role not least in development cooperation.

Klingebiel, Stephan. Development Cooperation: Challenges of the New Aid Architecture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137397881.0007.

1.1 Definitions, distinctions and scale

1.1.1 Definition

Development cooperation is generally understood to serve the purpose of assisting countries in their efforts to make social and economic progress. But is every form of cooperation with developing countries to be regarded as development cooperation? Who, in fact, determines whether a country is a developing country in the first place? What forms of cooperation should be seen as aid? Does military aid not help the recipient country too? What about commercial forms of cooperation; are they also to be seen as development cooperation? Should new forms of cooperation – as between China and African countries – also be regarded as forms of development cooperation?

Donors of development aid have agreed to lay down rules, especially within the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which has its own development committee, the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), mandated with tasks associated with development cooperation, known internationally as Official Development Assistance (ODA). The OECD considers not only appropriate standards for development cooperation, but also what distinguishes it from other areas. It is examining, for example, standards concerning forms of export subsidisation that may distort and obstruct competition. The interface between “development cooperation” on the one hand and, say, “unwanted distortion of competition” (due to export subsidies, for instance) on the other thus forms part of the debates on development cooperation arrangements.

The OECD’s Development Assistance Committee has agreed that the following criteria1 must be met if international assistance is to be recognised as development cooperation:

Although it is relatively clear to which category most countries belong, there are always doubtful cases. Qatar, Singapore (both until 1996), Hong Kong (until 1997) and Saudi Arabia (until 2008), for example, stayed on the list of developing countries for a long time. Some of today’s “donors”, such as Portugal, Greece and South Korea, were formerly on the “list of recipients”. In all, far more countries have been removed from the “list of recipients” (35) since 1970 than have been added to it (15; partly because of the collapse of the Soviet Union) (see, OECD/DAC 2011b).

Definitions are often difficult and politically sensitive in the development cooperation context. Time and again there are, for example, debates on why participation in UN peace-keeping missions in developing countries does not come under the heading of development cooperation (the costs have not hitherto been attributable to ODA) or why certain expenditure on accommodation for refugees in a donor country can sometimes be regarded as development cooperation.

Donors are very interested in there being a uniform definition of development cooperation because it will enable them to compare the various forms of assistance provided. International agreements reached under the United Nations’ auspices and political commitments by the eight leading industrialised countries (G8) have again and again helped to bring political pressure on the wealthy states to provide more development aid. As early as 1970 agreement was reached on the still controversial (non-binding) target set for the industrialised countries of devoting 0.7 per cent of their gross national income to development cooperation. Donors therefore have an interest in seeing as much as possible of their assistance recorded in international development cooperation statistics.

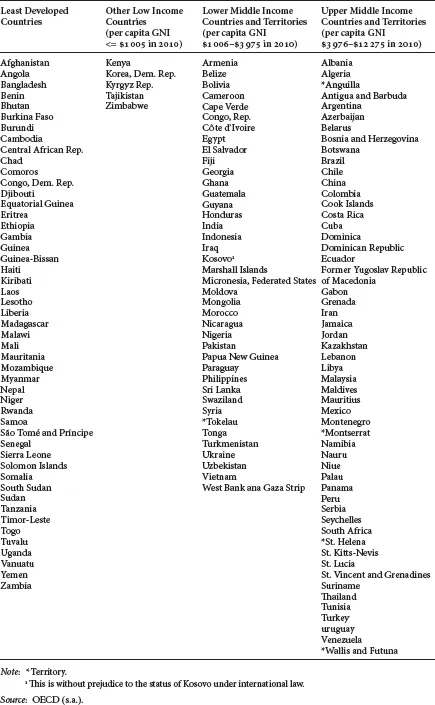

TABLE 1.1 DAC list of ODA recipients

1.1.2 Scale of development cooperation2

There are various ways of determining, describing and assessing the scale of development cooperation. These various perspectives are important when it comes to appraising donors’ contributions and the significance of those resources to developing countries. However, the question of “input” is only one relevant facet, since it does not initially say much about the effects achieved.

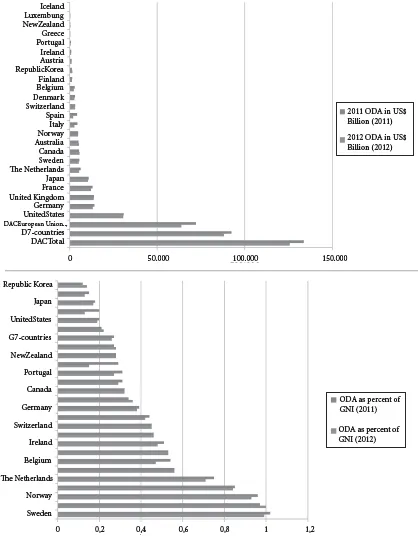

The donors who make up the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee provided a total of US$ 126 billion in 2012, the second year in succession in which the total fell in real terms. Measured against the donors’ economic strength, this was equivalent to 0.29 per cent of gross national income.

The USA continues to be the world’s largest bilateral donor of development assistance (US$ 30.5 billion or 0.19 per cent ODA/GNI in 2012). It is followed by the United Kingdom (US$ 13.7 billion or 0.56 per cent ODA/GNI), Germany (US$ 13.1 billion or 0.38 per cent ODA/GNI), France (US$ 12.0 billion or 0.45 per cent ODA/GNI) and Japan (US$ 10.5 billion or 0.17 per cent ODA/GNI). In relative terms, however, a number of small and medium-sized donors are far more heavily engaged, this being especially true of Luxembourg, Sweden, Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands, some of which contribute more than 0.7 per cent of their GNI. International non-governmental organisations provide a further amount of well over US$ 15 billion each year.

When all external financial inflows are considered, it is found that private flows have gained significantly on development aid in the longer term and exceeded it in most developing regions. Despite this, development aid continues to be important to the group of the poor and especially the poorest countries for the financing and implementation of poverty and reform programmes. In fragile countries it may be a vital means of counteracting signs of state collapse.

Most of the development assistance provided by donors goes to the countries of sub-Saharan Africa (37.9 per cent in 2010/2011);3 the proportion has been increased in the past at Asia’s expense and takes the comparatively strong economic dynamism of many Asian countries into account. Almost 10 per cent of OECD-DAC development assistance (8.4 per cent in 20114) is available in the form of humanitarian assistance, which is used to alleviate short-term emergency situations.

Over 17 per cent (2010) of aid is provided in (partly) tied form and recorded as such; the provision of aid in these cases is subject to the requirement that goods or services are purchased from the donor country. Owing to the absence of international competition, tied aid is more expensive on average and may be of a poorer quality than would result from international calls for tenders. The costs due to the tying of aid are some 15 to 30 per cent or, in the case of food aid, as much as some 40 per cent higher than when aid is not tied (Clay et al. 2009, 1). For the sake of development, the abandonment of aid-tying has therefore been demanded for decades. The officially designated instances of aid-tying (as in the case of goods) are joined by other de facto tied aid, as in the context of technical assistance, when partner countries are not free to put advisory services out to tender. This practice is similarly criticised as being bad for development (for example, Actionaid 2011; Clay / Geddes / Natali 2009, viii).

FIGURE 1.1 Donor performance, 2011–2012

Source: Author’s own compilation, data from: BMZ (2013).

In certain circumstances, the cancellation of debts (primarily export credits) may also be recognised as development aid. In the past two decades this step was often an important means of reducing the heavy burden of amortisation and interest payments on the budgets of many developing countries – a problem that remained serious until the late 1990s. Where debt cancellations came in for criticism, it was because they do not make any additional resources available to countries for development purposes, but rather reduce the outflow of resources (for example, Actionaid 2011).

1.1.3 Importance of development cooperation from the developing countries’ viewpoint

Development cooperation varies widely in its importance to developing countries. While a group of poor countries continues to be heavily dependent on it, in some respects it now plays no more than a marginal role for other developing countries. Dependence on development cooperation is usually expressed as the ratio of development assistance to a developing country’s economic strength (aid/GNI) or as aid in absolute terms per inhabitant of the recipient country (aid per capita). In the first method, the importance of deve...

Table of contents

Citation styles for Development Cooperation

APA 6 Citation

Klingebiel, S. (2013). Development Cooperation ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3488995/development-cooperation-challenges-of-the-new-aid-architecture-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Klingebiel, S. (2013) 2013. Development Cooperation. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://www.perlego.com/book/3488995/development-cooperation-challenges-of-the-new-aid-architecture-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Klingebiel, S. (2013) Development Cooperation. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3488995/development-cooperation-challenges-of-the-new-aid-architecture-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Klingebiel, S. Development Cooperation. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2013. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.