- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In politics, business and society, 'better' leadership and dialogue are seen as antidotes to the paradoxical issues of the modern world. This book illustrates how the compulsion for 'busyness', the assumptions about who leaders are and the adherence to implicitly-held cultural norms threaten the possibility of effective dialogue in organizations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dialogue in Organizations by M. Reitz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Relational Leadership and Dialogue: A Gap in Knowledge

Introduction

The objective of this chapter is to examine the relational leadership literature and the literature on dialogue together in order to explore how the between space of dynamic leadership relation has been conceptualized to date.

In order to do this an overview of the body of literature examining relational leadership theory (RLT) will be presented positioning it within the wider leadership literature. It will be explained how, very recently in RLT, the leader–follower relation has been conceptualized as ‘dialogic’. This leads on to an exploration of the term ‘dialogue’ through an overview of the literature. This will show how multi-faceted understanding of the term is. The concept of I–Thou dialogue identified by Martin Buber (1958) is detailed with an explanation as to why his work might be particularly well suited for responding to various calls within RLT to expand our understanding of the leader–follower dynamic. Then follows a summary of the limited occasions in which the two fields of dialogue and leadership and the specific areas of relational leadership and I–Thou dialogue have been brought together to date.

Relational leadership

Overview of the leadership literature: positioning relational leadership

This section provides a brief overview of the vast leadership field illustrating how the focus of attention within it has changed over time and thereby situating relational leadership theory which this book focuses on. By illuminating the historical context in which this book has been developed I recognize one aspect of why I may have been driven to ask the questions that I am asking at this point in time, situated at this place in history and in this place socio-culturally.

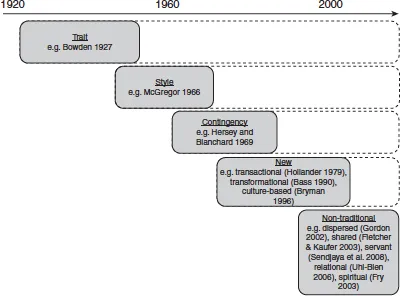

Figure 1.1 Historical evolution of leadership theories

Source: Based on Gordon (2002) and modified by author.

There have been many attempts to classify and summarize the leadership field (see, e.g., Grint 2005, Jackson and Parry 2008 and Yukl 2002), all of which aim to make the immense field of leadership more manageable. They illustrate how diverse perspectives are, from theories which explore the leader’s unique and special attributes, to those which argue that more emphasis should be placed on the process of leadership and how individuals recognize and create leadership with those around them. Broadly speaking if one examines the field historically one can see how the emphasis from the former to the latter has evolved.

Using a classification provided by Gordon (2002), modified to include other very recent interests in the leadership field, Figure 1.1 illustrates the historical development of the literature from the early twentieth century when mainstream management theorists began to take a significant interest in organizational leadership.

This is a simplification of the field of course; for example, it is of note that today there are still significant numbers of trait leadership theories being posited and published (e.g., Judge et al. 2009 and Kant et al. 2013). Nevertheless the diagram does indicate the main time periods in which various theories have been generated and when they remained most popular.

Gordon (2002:159), writing as a supporter of dispersed leadership theories, asserts that those theories in the first four categories in the figure and referred to as ‘traditional’ by him are generally founded on ‘concepts of differentiation (clear boundaries of identity between leaders and followers) and domination (the “natural” superiority of the leader and the giving over of will by followers)’. However dispersed theories, he claims (and I have added also the recent interest in relational, shared, servant and spiritual leadership to term these theories ‘non-traditional’), are generally founded upon ‘concepts of dedifferentiation (blurred boundaries of identity between leaders and followers) and collaboration (sharing of power between leaders and followers)’ (159).

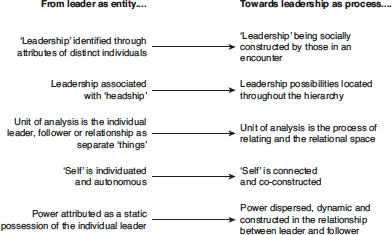

However there is a further important movement which Gordon does not refer to, perhaps because it was in relative infancy when he wrote in 2002. That is the growing interest in the process of leadership and how leadership is constructed dynamically in relation rather than on the leader and follower as entities. This movement has been identified by authors such as Cunliffe and Eriksen (2011), Hosking (1988), Ladkin (2010), Uhl-Bien (2006) and Uhl-Bien and Ospina (2012) amongst others. This discernible movement in focus towards the leader–follower relational space has been termed a ‘relational turn’ (Ospina and Uhl-Bien 2012b). Figure 1.2 summarizes my understanding of five important characteristics of this movement.

Whilst this appreciation for the dynamic relational process between leader and follower is growing and might indeed herald a paradigm shift in the field (as argued by Fletcher 2004, Ospina and Uhl-Bien 2012b and Uhl-Bien 2006), it is recognized that the entity perspective in leadership research still predominates in both academic and practitioner publications (Ospina and Uhl-Bien 2012a).

Regardless of whether or not this movement in the leadership literature represents a paradigm shift, the debate between opposing ontological and epistemological views, and its consequences, is clearly brought into focus through the on-going ‘dialogue’ (see Day and Drath 2012 and Ospina and Uhl-Bein 2012b) between relational leadership theorists of widely varying perspectives to whom I now turn.

Figure 1.2 The relational turn in the leadership literature

Source: Author’s own with reference to Ospina and Foldy 2010, Ospina and Uhl-Bien 2012b and Uhl-Bien 2006.

Relational leadership theory

As described earlier, a development which has occurred primarily in the past 20 years is the growing field of relational leadership. Relational leadership could be seen to encompass a rather expansive array of claims regarding the nature of the relationship between leader and follower. Uhl-Bien fortunately however paved the way for clarification in her 2006 Leadership Quarterly article which outlines two main perspectives of relational leadership which are reflected in Figure 1.2. The first is an entity approach ‘that focuses on identifying attributes of individuals as they engage in interpersonal relationships’ (654). The second is a relational perspective ‘that views leadership as a process of social construction through which certain understandings of leadership come about and are given privileged ontology’ (654). Relational leadership theory is then offered by Uhl-Bien as ‘an overarching framework for the study of leadership as a social influence process through which emergent coordination ... and change ... are constructed and produced’ (654).

In other words, according to Uhl-Bien (2006), who builds on the work of Dachler and Hosking (1995, Hosking 1988, 2007), the leadership literature domain can be divided into two. Firstly there are those scholars who perceive leaders as possessing certain qualities with relationship as an exchange between leader and follower. This view focuses on the attributes of the leader, the follower and the relationship as ‘things’ that can be studied and to a certain extent objectified. Well-known examples of this perspective are leader-member exchange (LMX) theory (e.g., Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995) and charismatic leadership theory (e.g., Shamir et al. 1993). These views regard the self as an independent entity to whom agency is ascribed with a clear separation of mind and nature (as explained by Fitzsimons 2012 and Uhl-Bien 2006). The epistemological implications of this entity perspective are profound. Methods such as those found in the natural sciences are seen as being appropriate to discover the objective reality of a leader and leadership.

This is in contrast to a more recent focus in the leadership literature, described earlier, on the process of leadership; examining how, when people are in a relationship, the phenomenon of leadership is dynamically constructed and how each person in that relationship is changed as a result of that meeting. Writers such as Mead (1934) and James (1890) are seen as the forefathers of this perspective which is referred to as social constructionism (see Berger and Luckman 1966). In this view, the spotlight falls on how individuals make meaning from the interaction, how they understand leadership and how this understanding forms as a result of socio-historical factors. In this sense leadership and indeed followership are clearly phenomena of interpretation and subjective assessment, in constant flow, as opposed to labels accorded statically and permanently to individuals. The notion of self is regarded as problematic; the focus rather is on how we come to construe separation and how the concept of self derives from relational processes. Barrett et al. (1995), Bligh et al. (2007), Fairhurst and Grant (2010), Gergen and Gergen (2008), Hosking (2007, 2011) and Ladkin (2010, 2013), amongst many others, are examples of authors currently writing from this point of view.

Reiterating some of the points in Figure 1.2 Uhl-Bien argues that the relational perspective (which she later termed ‘constructionist’ in order to provide clarity; see Uhl-Bien and Ospina 2012) initiates possibilities for leaders and leadership which are fundamentally different from the previous entity view. Firstly it ‘recognizes leadership wherever it occurs’ (Hunt and Dodge cited in Uhl-Bien 2006:654). In other words it does not restrict leadership to those in hierarchical positions; leadership does not only happen in a manager-subordinate situation, where leadership is equated to ‘headship’.

Secondly it shifts focus onto processes rather than persons. Constructionist perspectives therefore ‘identify the basic unit of analysis in leadership research as relationships, not individuals’ (Uhl-Bien 2006:662) and as such ‘processes such as dialogue and multilogue become the focus’ (663). This in turn implies a focus on different methodologies in order to access such processes which will be considered further in this chapter.

Thirdly knowledge in constructionist thinking is rather obviously viewed as socially constructed, in other words, our meaning making is influenced by our socio-historical position and the opinions, thinking and actions of those around us. Uhl-Bien (2006:655) reminds us that ‘meaning can never be finalized ... it is always in the process of making’. Those propounding a relational turn claim our predominant understanding of the term ‘leader’ appears to be undergoing a change in its meaning, away from ‘special and superior’ and towards something which allows more space for dynamic two-way influence.

Uhl-Bien and Ospina (2012) recently set out to provide more clarity to the field of RLT in their edited volume Advancing Relational Leadership Research. This work attempts to further explain the distinction between entity and constructionist views. For example, the ‘dialogue’ between Hosking and Shamir (Hosking et al. 2012, Hosking and Shamir 2012, Shamir 2012) highlights passionate differences in worldviews and approaches. However the editors and many of the authors acknowledge that the distinction is often not perhaps quite as black and white as Uhl-Bien’s 2006 article and the distinction laid out earlier supposes. On reading the chapters presented I perceive a movement towards a ‘middle ground’ in some of them. The metaphor that keeps coming to my mind is of the two main UK political parties who represent different ideological bases, but on examination of policy it is sometimes difficult to draw much of a distinction between them.

I suggest that some ‘entity’ writers, such as Ashkanasy et al. (2012) and Treadway et al. (2012), clearly come from a post-positivist persuasion and express this through their language. For example, Treadway et al. (2012:382) attempt to ‘depict the mechanisms through which communication processes operate’ and Ashkanasy et al. (2012:352) ‘consider the key affective exchanges between leaders and followers as a key determinant in shaping relational leadership outcomes’. However despite this causal mechanistic outlook the words ‘relation’, ‘relational’ and ‘relationships’ infuse their work. They clearly show that they appreciate that ‘leaders’ are constituted through others perceiving them as such in relation. They see leaders as sitting within a field of relationships, and they firmly state that navigating these relationships is essential to the leader role.

From the other direction, constructionist writers, such as Ospina et al. (2012) and Fletcher (2012), whilst focusing more on leadership process, nevertheless seem keen to study positional leaders and help to articulate ‘what leaders should do’ to be more effective. Ospina et al. (2012:286) present a framework that entails ‘a set of leadership drivers’ and they ‘acknowledge that the entity perspective has informed much of [their] thinking’. Fairhurst (2012:100) considers ‘adding the element of personal agency’, more common to the entity perspective, to constructionist thinking. She seeks to avoid ‘the dangers of focusing on one [perspective] to the exclusion of the other’ whilst realizsing the ‘advantages of holding them together’ (84).

Hence I suggest it is a little more difficult to discern strict chasms in ontological assumptions than perhaps the straightforward distinction between entity and constructionist research that Uhl-Bien’s 2006 article implies. This move to the middle ground could be for a number of reasons. It may have been driven by greater attempts to cross boundaries and appreciate other views and work. Advancing Relational Leadership Research was a specific attempt to counter the ‘fault zone’ (Uhl-Bien and Ospinas 2012:xvi) in leadership studies on the understanding that ‘multi-paradigmatic approaches’ (Uhl-Bien 2012:xv) were needed to advance knowledge of relational leadership. Such attempts may be instrumental in widening knowledge of leadership through real efforts to understand, appreciate and incorporate alternative views.

Perhaps this convergence is because some authors are trying harder to appeal to a wider audience. Entity writers may wish to acknowledge and incorporate aspects of the constructionist agenda, showing that they are appreciative of the implications of the recent relational turn. Constructionists, perhaps in an attempt to be published by journals that continue to privilege a more positivist approach, seek to emphasize how their methods conform to more traditional academic definitions of validity and offer generalized conclusions more characteristic of an entity perspective. This leads me to wonder whether the methodological approaches applied to the leadership field might be narrowed as both ends of the spectrum ‘play it safe’.

The middle ground might have assumed more prominence in response to pragmatic experience. Perhaps it has become less reasonable or ‘sensible’ to assume positions at the far edges of the spectrum. We are cognisant of the inability of well-known leaders to navigate predictably through uncertainty and ambiguity, influencing others to behave in ways that they wish (e.g., Obama, Cameron and other world leaders in relation to the Syrian conflict). Therefore claiming that such leaders are independent and possess agency which can, if it is examined in sufficient detail, mechanistically drive the environment around them simply does not stand up to our experience. Conversely, we understand that some leaders have seemed, through their own attributes in relation to others and through their own agency, to have made a lasting impact on those around them (Mandela’s legacy is an example that is hard to deny).

Finally authors have emerged, such as Fitzsimons (2012), who have approached RLT from different disciplines (in his case systems psychodynamics), which appear to engage less problematically with aspects of both entity and constructionist views. They claim to include both perspectives, for example, Fitzsimons’s accounts for the influence of the collective on the individual and vice versa.

I am presenting this move to the middle ground as neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad’; however one implication might be that the clarity regarding ontological foundations is ‘muddied’. To return to the metaphor of the UK political scen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Relational Leadership and Dialogue: A Gap in Knowledge

- 2 Relational Leadership and Dialogue: Applying an Action Research Approach

- 3 Presence: The Tyranny of Busyness and Its Affect on Relational Leadership and Dialogue

- 4 Rules of the Game and Faade: Being Rather Than Seeming

- 5 Power and Judgements: LeaderFollower Mutuality

- 6 Dialogue: Sensing Relational Encounter Amidst Complexity

- 7 Towards a Theory of LeaderFollower Encounter

- 8 Relational Leadership and Dialogue: A Personal Reflection

- References

- Index