eBook - ePub

XVA Desks - A New Era for Risk Management

Understanding, Building and Managing Counterparty, Funding and Capital Risk

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

XVA Desks - A New Era for Risk Management

Understanding, Building and Managing Counterparty, Funding and Capital Risk

About this book

Written by a practitioner with years working in CVA, FVA and DVA this is a thorough, practical guide to a topic at the very core of the derivatives industry. It takes readers through all aspects of counterparty credit risk management and the business cycle of CVA, DVA and FVA, focusing on risk management, pricing considerations and implementation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access XVA Desks - A New Era for Risk Management by I. Ruiz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Context

1 | The Banking Industry, OTC Derivatives and the New XVA Challenge |

Before going into the details of the XVA world, we want to understand where it fits in the whole financial and banking system. In this chapter, we are going to see the basics of how banks work and operate, where the world of derivatives fits in and what is XVA to that world.

Financial institutions are extremely complicated entities these days. Because of that, the overview that is given in this chapter is, purposely, somehow over-simplistic. Otherwise the reader may get lost with details not well understood while missing the broad picture.

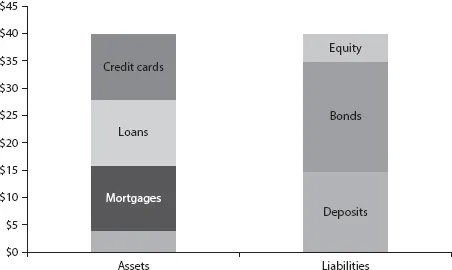

1.1A simple bank’s balance sheet

Balance sheets are the accounting tool used to produce a snap shot of a bank’s financial position. Let’s have a look at them. In order to do this, we are going to build a balance sheet from the ground up. It is going to be a very simplified picture, to ensure that the key points are not missed out.

1.1.1The banking book

In order to understand how banks operate, let’s create a “toy” bank model.

Let’s say that a collection of ten investors decide to create a bank from scratch. To do this, each of them provides, say, $1, and so the starting bank funds are $10, and ten equal shares are given to those investors. In accounting terms, this translates into the balance sheet of the bank so that it has assets of $10 (the money given by the investors) and equity of $10 too (the shares).

As a first line of business, the bank can take deposits from customers and keep their money safe in a vault. It can then provide some useful basic financial services like paying bills directly, debit and credit cards, cheque books, transfer money to another account in another bank on the client’s behalf, etc., for which the bank will charge a fee. Let’s say that the bank has received another $15 in deposits. Now the bank’s balance sheet has $25 in assets (the money it has in its vaults), $15 in money owed to customers (the money deposited by clients), and $10 in equity.

Now, here comes a second and most important line of business: the bank realises that from the $15 it has from depositors, it only needs to have readily available, say, $4; the other $11 are always sitting in its vaults and nobody ever claims them in practice. So it decides to lend money out and charge for it. It can lend out the $10 that it had originally from the bank owners, and the $11 that are never used. In this way, it can lend out to other customers $21. For the sake of argument, let’s say that the rate at which the bank is lending out that money is 10% per year.

Going further, the managers of this toy bank realise that there are lots of potential clients wanting to borrow money at a 10% rate, so it decides to go to other financial institutions and borrow money at, say 4%, and then lend it out at 10%, hence making 6% per year on these operations. Let’s say it borrowed $20, and let’s refer to these loans as “bonds”.

We are going to illustrate this graphically, but before doing so let’s go one step further. In practice, our toy bank faces different sorts of borrowing requirements from clients. For example, some clients want to buy a house with a loan and are happy to secure it with the house itself (a mortgage), so the bank is happy to lend at a lower rate of, say, 6%, as the potential losses it faces in mortgages is lower than in unsecured loans.1 Also, other customers want to be able to do instantaneous purchases of small items (e.g., buy a TV set) and so they are happy to pay a high interest if the bank can help them buy those purchases whenever they want and pay back to the bank in a few months, without asking any questions, without any fuss. These are credit cards. Our toy bank decides to charge a 20% interest rate on them as the potential losses (i.e., customers not paying back the loan) from those credit card loans are greater than those from common loans.

So, to summarise, the bank is taking money from different sources. It is keeping part of it as cash, to cover the demand for money from the depositors, and it is also lending the rest of the money out to different customers in various forms. The taking of money constitute the bank liabilities (equity from bank owners, deposits, bonds) and what it has and gets with that money are the assets (cash, loans, mortgages, credit cards).

Figure 1.1 illustrates how the balance sheet of our toy bank looks. Readers should note that, always, assets are equal to liabilities.

Figure 1.1Example of a simplified banking book

So far, the picture of our toy bank has been static. That is, we are considering the assets and liabilities of the bank at a given point in time. However, the value of the assets in a bank changes over time. Let’s suppose that the bank holds some cash in a foreign currency. In this case the value of that cash will change over time following the exchange rate (FX Risk). Another source of change in value can come from changes in the present value of future money2 (Interest Rate Risk). Another source of change in value can come from the fact that, for example, we realise that the default rate of a number of loans that we have in the past is higher than originally expected and, so, the balance sheet should reflect this and decrease the present value of those loans3 (Credit Risk). In general, a bank can have on its balance sheet other assets, like equity for example, that will change in value over time.4

Right now, the main point is to realise that the Asset side of the balance sheet of a bank fluctuates in value with time. The statement that reflects the changes in that value is the “Profit and Loss” statement of the bank for the period under consideration. As said, a fundamental law of accounting is that assets must be equal to liabilities. However, the liabilities that the bank has to its creditors (via deposits and bonds in this toy bank) do not change, so any profit or loss on the Asset side of the balance sheet is absorbed by the Equity: keeping the non-equity liabilities constant, when the bank balance sheet increases in value, the equity increases in value with it, and vice versa.

For the sake of completeness, in addition to the balance sheet and the profit & loss statements, a third important piece of information is the cash-flow statement, that states the cash that has gone in and out of the bank. We are not going to use it, but it is good to mention it here for completeness.

Everything seen so far in this section is called the banking book of a bank. We are going to see the different other parts of the balance sheet in the next sections.

1.1.2The trading book

So far, every one of the assets and liabilities we have seen are “physical” in the sense that they require the transmission of relatively large amounts of money at the beginning and at the end. The bank takes deposits today and will give it back when the clients demand them, in a loan the bank gives the cash today and it will received it back in the future, etc. However, a bank can trade also financial derivatives that are less cash intense, but that can be very important for a bank and can carry a high quantity of risk. Let’s give a few examples.

Our toy bank has a car manufacturer in Germany as a client; for example, BMW. BMW sells around 20% of its cars in the US.5 Obviously, the price of the cars it sells in the US is fixed each year in US dollars. So, BMW faces foreign exchange (FX) risk in this department: it does not know how many euros it will receive for a given number of cars that it sells in the US. Companies do not like uncertainty, and even less uncertainty that is outside their core business, which is car manufacturing in this case. As a result, BMW will be happy to hedge out this FX risk: they like to know that for every car they sell, they get a fixed amount of euros; then, they will make sure they sell lots of cars, as that is their core business.

So, our toy bank steps in and offers BMW the following product: let’s say that today’s EURUSD exchange rate is 1.2, and that BMW wants to protect $120 million of sales, that are €100 million today. Our bank is going to sell to BMW a contract that is settled in 1 year, that is going to compensate for any loss in euros coming from changes in the FX rate. Also, they agree that any gain that BMW has in euros, should the FX rate move in its favour, will be delivered to our bank. In other words, if BMW loses euros because the FX rate goes against them, then the bank gives that loss to BMW, but if it gains euros because the FX rate moves in BMW’s favour, then the bank receives that gain from BMW.

In this way, BMW is happy because it knows that if it sells its expected 4,000 cars at an average price of, say, $30,000, it will receive $120 million that, then, will transform into €100 million exactly, regardless of what happens to the EURUSD exchange rate during this year. This is, more or less, a very simple derivative called “FX forward”.

However, the story does not finish here, as our toy bank may have another client in the US that has the same but symmetric problem: it sells, for example, computers in Europe, but makes its accounts in US dollars, so it likes stability in this later currency. So, our toy bank can sell the same but opposite product to that American company (Apple Computers, for example). In this way, everyone is happy: BMW has hedged out its FX risk, Apple Computers has hedged it out too, and the bank is sitting in the middle, making a fee for this risk transfer service.

In practice, financial derivatives can be most complicated; this is a very simple and somewhat idealistic example. Banks have developed a whole range of financial derivatives that range from a simple forward to other very sophisticated contracts customised to customers’ needs. With these derivatives, banks offer a channel to transfer and mitigate risk. Banks can offer these derivatives in all sorts of markets: FX, interest rates, equity, credit, commodities, weather, insurance, etc.

From the bank’s point of view, the part of the balance sheet that deals with the value of these assets is called the trading book. As we will see, the value of the trading book can change very rapidly, as it is very sensitive to market variables, that swing around permanently. For this reason, while the banking book is typically marked (that is, it is valued) from time to time (e.g., monthly), the trading book needs to be marked daily.

A key feature of the trading book is that, ideally, a bank uses this type of trade to offer, only, financial services and so it should be, in theory, market neutral. By this it is meant that, following our example, the changes in the value of the FX forward done with BMW will be the same and opposite to the FX forward done with Apple Computers. As a result, in principle, the value of the trading book should be neutral to swings in the market variables. However, things are usually not like that, for a number of reasons. These include that a bank may choose to not be market neutral and have a directional position in some markets (e.g., to benefit if the EURUSD increases at the risk of losing money if it decreases), perhaps the nature of the market it operates does not let the bank be market neutral, perhaps the systems it has in place do not let the bank see the risks it has taken6 … there could be many reasons.

In practice, banks cannot become market neutral relying only on trades done with clients directly. So, in order to manage these risks, banks have access to a wholesale market of financial products that they can trade with each other to transfer risk between them. This is why this part of the book is call the “trading” book: banks trade these financial derivatives constantly with each other in order to offer the services they are required and to hedge out their risk. As a result, the number and nature of the trades sitting in the trading book is quite unstable, it can change very quickly.

To add some more complexity, the notion of the trading book is usually expanded to some products that can live both on the banking and trading book depending on the bank’s intentions with respect to them. For example, a bank can decide to lend money to the US government for ten years by buying a ten-year treasury bond. If it decides to lend that money and wait for ten years to get the money back, then this bond should sit on the banking book. However, the treasury bond market is very liquid (that is, you can sell and buy these bonds very easily), and the bank may decide to buy this bond today, hold it for ten days and sell it again for whatever reason. If so, then this bond typically goes into the trading book of the balance sheet.

So, in reality, the trading book should comprise those products that are “actively” trade...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Disclaimer

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Part I The Context

- Part II Quantitative Fundamentals

- Part III The XVA Challenge

- Part IV Further to XVA

- Part V Appendices

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index