eBook - ePub

Developing Online Language Teaching

Research-Based Pedagogies and Reflective Practices

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Developing Online Language Teaching

Research-Based Pedagogies and Reflective Practices

About this book

When moving towards teaching online, teachers are confronted every day with issues such as online moderation, establishing social presence online, transitioning learners to online environments, giving feedback online. This book supports language teaching professionals and researchers who are keen to engage in online teaching and learning.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction: From Teacher Training to Self-Reflective Practice

Regine Hampel and Ursula Stickler

Focus of the book

This book has been written to meet the need of language teachers who are keen to engage in online teaching and learning contexts, teacher trainers in search of resources that they can use with their trainees to develop their online teaching skills, and researchers in language pedagogy looking for well-founded studies and recommendations in this area. It integrates technology and pedagogy as well as theory and practice, and will help teachers in formal, non-formal and informal settings to become confident users of online tools and to relate their pedagogical practice to online learning situations as well as giving them a basic understanding of selected theories. Readers will be able to use this volume in the context of independent self-training and pre-service teacher training courses, for in-service staff development and also for establishing their own research projects. As befits the content, the book is modular rather than linear, and certain elements can be taken out of context and used independently for self-training or institutional training events.

When moving towards teaching online, teachers are confronted every day with challenges such as online moderation, establishing social presence online, transitioning learners to online environments and giving feedback online. This book, without explicitly focusing on specific issues, is designed to help teachers consider the skills they have and how they can develop these further. The authors are taking a broad perspective, looking at the need to self-train and the challenges around it, the skills that are required to use information and communication technology (ICT) in language teaching contexts, the online communities that teachers can tap into for support, other resources available for initial training as well as continuing professional development on the internet, and the role of open educational resources. The book also tries to inspire teaching practitioners to do their own research, helping them to position themselves theoretically and methodologically and to find out if what they do online with their students works and how it can be improved. Teacher trainers will find this book helpful for pre-service and in-service training of teachers. All elements of the book acknowledge the need for reflective practice, encouraging readers throughout to place their own experience in context and reflect on developmental options.

Hubbard and Levy (2006a, p. ix) identified a number of themes that recurred in their edited book on teacher education in CALL (computer-assisted language learning):

• the need for both technical and pedagogical training in CALL, ideally integrated with one another;

• the recognition of the limits of formal teaching [in the context of CALL training] because the technology changes too rapidly;

• the need to connect CALL education to authentic teaching settings, especially ones where software, hardware, and technical support differ from the ideal;

• the idea of using CALL to learn about CALL – experiencing educational applications of technology first-hand as a student to learn how to use technology as a teacher;

• the value of having CALL permeate the language teacher education curriculum rather than appear solely in a standalone course.

These themes, on the whole, are still valid today and also guide the approach to CALL that the authors in this book have been following. Almost ten years later some of Hubbard and Levy’s (2006a) recommendations still remain to be implemented. In many contexts, there is still insufficient training in CALL, and often the technical and the pedagogical elements are not integrated (see Chapters 2 and 3). Many teachers feel that while they may receive training for using ICT in the classroom, the resources on the ground are still inadequate for them to use computers in their daily practice (see Chapter 11).

In their own teaching, teacher training and research, the authors in this book believe in giving teachers hands-on experience of using ICT and share a learner-focused perspective that helps students to use the computer to connect with others, thus developing their own knowledge. An example of how CALL can help teachers learn about CALL is the DOTS (Developing Online Teaching Skills) project, funded by the European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML). Seven of the book’s authors have been involved in this project – which is also at the centre of Chapter 10.

Acknowledging the seminal influence of Hubbard and Levy (2006a), this book adds to their agenda in several ways. Expanding on work done previously (Hampel & Stickler, 2005), it focuses specifically on the skills that teachers have to develop to teach successfully online. It also deals with current issues of sharing and learning together, thus pointing to one way of dealing with the consequences of Hubbard and Levy’s second point above. Collaboration has become crucial in the way teachers gather information and develop expertise, work together in communities of practice, and develop and use open educational resources and practices. In addition, the book emphasizes the need for teachers to carry out their own research. Accordingly, it calls for teaching professionals to become aware of the theoretical and pedagogical models that underlie online teaching and learning and to research their own practice.

Theoretical rationale

The chapters in this book are united by sociocultural and socio-constructivist approaches to teaching online, approaches that go back to the work of the developmental psychologist Lev Vygotsky in Russia in the 1920s. Vygotsky (1978) stressed the importance of the social in learning – an idea that was taken up by Wertsch in his work on sociocultural theory more than half a century later. ‘The basic goal of a sociocultural approach to mind is to create an account of human mental processes that recognizes the essential relationship between these processes and the cultural, historical, and institutional settings’ (Wertsch, 1991b, p. 6).

Similarly, socio-constructivism brings in the social element to build on constructivism, a theory of knowledge that assumes that humans construct their own knowledge and make sense of the world based on their own experiences in a complex and non-linear process. ‘Incorporating influences traditionally associated with sociology and anthropology, this perspective emphasizes the impact of collaboration, social context, and negotiation on thinking and learning’ (Hinckey, 1997, p. 175).

In the area of language learning research, in 1997 Firth and Wagner called for an epistemological and methodological broadening of second language acquisition (SLA) that included ‘a significantly enhanced awareness of the contextual and interactional dimensions of language use’ (Firth & Wagner, 2007, p. 801; see Firth & Wagner, 1997). This formed part of the ‘social turn in second language acquisition’ as Block (2003) has called it:

a broader, socially informed and more sociolinguistically oriented SLA that does not exclude the more mainstream psycholinguistic one, but instead takes on board the complexity of context, the multi-layered nature of language and an expanded view of what acquisition entails. (p. 4)

Sociocultural and socio-constructivist ideas can be seen to inform this book in various ways. Chapter 2 focuses on language teachers’ needs in terms of training, and Chapter 3 takes account of teachers’ institutional contexts as part-time or freelance staff. Chapter 4 shows the relationship between the teacher and the learner in terms of expectations, and in Chapter 5 the importance of the social in the context of language teaching skills is highlighted. Chapters 6 and 7 focus on the impact of sharing resources and practices; an idea that is developed further in Chapter 8 which argues for the central role of peer support through communities of practice. Chapter 9 examines theoretical and pedagogical approaches to online language teaching from a sociocultural perspective, and Chapter 10 shows the importance of shaping training to teachers’ needs and of learning collaboratively. Last but not least, Chapter 11 highlights some of the issues that language teachers and learners face within their institutional settings in Turkey.

A model for online teaching skills

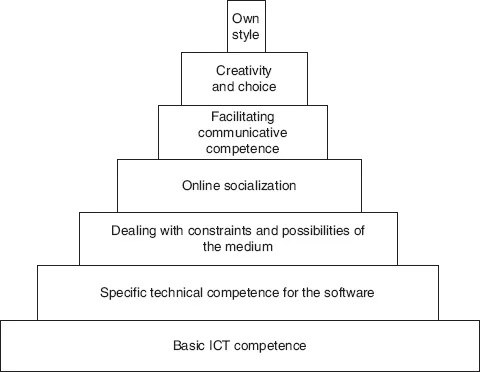

When we were working with teachers in the early 2000s to introduce web conferencing in language courses at the Open University, it became clear to us that teachers had to develop new skills to be able to successfully use the new online tools with which they were expected to teach. Although there were pockets of development in terms of websites, courses and other resources (for example, Graham Davies’ ICT4U, the EU-funded Medienpass project, or the Webheads who freely provided in-depth training in the use of web communication tools for EFL/ESL teachers from 2004, see Almeida d’Eça & Gonzáles, 2006), training was not widely integrated into colleagues’ practice and the perception was that what worked well in face-to-face settings could easily be transferred to online environments. This, however, had been disproved in some of the early trials that had been carried out at the Open University with various online communication tools (see Hampel & de los Arcos, 2013). So we set about developing a model specifically for online language teaching that tried to bring together the various skills that this form of teaching requires of teachers and integrated pedagogy with technology. This resulted in the skills pyramid in Figure 1.11 which will be elaborated in Chapter 5.

Since the mid-2000s the sophistication and choice of ICT for language teachers has proliferated, and teachers (as well as students) are increasingly becoming more familiar with the use of new technologies in the classroom. However, our work with the European Centre for Modern Languages (part of the Council of Europe) and the European Commission has shown that there is still a need for teacher training in CALL. An initial needs analysis carried out in 2008 in the context of the DOTS project showed that while teachers rate ICT highly (for example, in terms of authentic communication, collaboration, access to up-to-date information, exam preparation, development of autonomous learning and critical thinking, and flexibility), only half of the respondents had received formal training. Subsequent evaluation with teaching professionals who attended DOTS workshops has confirmed this initial finding and other reports that have been published (see Chapter 2).

Figure 1.1 Skills pyramid

Source: Hampel & Stickler (2005, p. 317).

Chapter overview

In terms of its structure, the book can be compared to a travel handbook, guiding novice online language teachers on a journey towards successful integration of ICT elements into their online or blended teaching. For some readers the first stages will not be necessary, as they are already well aware of their own needs and skills levels. Those readers can explore the more specific suggestions provided later or read the first chapters for information and to compare their own teaching context with those of fellow teachers across Europe and beyond. For others, having a structured approach – from needs to expectations, skills, training suggestions, towards peer support and action research – will provide a valuable means of supporting their progress.

In line with our socio-constructivist approach to learning, every chapter has a reflective task at the end. This should help the reader to engage more deeply with the content matter of the chapter, allow evaluation of progress and depth of understanding, and bring the relevance of the chapter within the reader’s own frame of experience.

The book starts with the needs of language teachers who are integrating ICT into their teaching. Rather than taking the expert view from outside (or above), the authors start by inquiring about language teachers’ situation with respect to ICT integration, their actual teaching practice and the best practices they are aspiring to and, most crucially, their perceived training needs. Considering a variety of teaching situations, from formal teaching of languages in compulsory and post-compulsory education institutions to informal language mediation in voluntary and migration contexts, and taking into account a scale of different employment contexts (i.e. full-time, part-time, casually employed, or volunteering), the next two chapters present our attempt to understand the emic perspective on the changing situation of language professionals in an increasingly digital world. We hope that in Chapters 2 and 3 every language educator, teacher trainer or trainee teacher will find their dilemmas and challenges reflected to some extent.

Leading on from establishing the needs and challenges of teachers, Chapter 4 then takes the mirroring perspective of language students and asks what learners expect from their online teacher. This perspective helps not only to give the learner a voice in shaping a successful online teaching/ learning environment, it also allows teachers to mould their training and preparation to adapt to or adjust the expectations of their learners.

Teaching skills, as they have to be developed and adapted for online language teaching, are the central focus of Chapter 5. That language teachers need to prepare specifically for an environment that, to the novice, may offer little in non-explicit non-verbal communicative cues, has been an established tenet of online language teacher training for more than a decade. Based on our skills pyramid for online teaching (Hampel & Stickler, 2005), we consider the changes in the online world of learning and teaching over the past ten years and how these have influenced the development of online teaching skills. Changes are not only occurring in the form of technical advances and in terms of accessibility and use of online communication tools, but there are also shifts in pedagogic emphasis and the mindset of users, digital natives, immigrants, residents and sojourners. Skills such as basic ICT competence, still a necessary consideration in 2005, are now taken for granted by almost all employers, national agencies for education and by learners themselves (as shown in the changing expectations of students, see Chapter 4). There is, however, now an increased need for the negotiation of online spaces as learning spaces, which will be discussed in Chapter 5.

Having established training needs and necessary skills, Chapter 6 provides some much needed practical guidance on utilising free online resources for self-training and integrating online resources into language classes. The overview of online training resources for l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 Introduction: From Teacher Training to Self-Reflective Practice

- 2 European Language Teachers and ICT: Experiences, Expectations and Training Needs

- 3 Part-time and Freelance Language Teachers and their ICT Training Needs

- 4 Online Language Teaching: The Learner’s Perspective

- 5 Transforming Teaching: New Skills for Online Language Learning Spaces

- 6 Free Online Training Spaces for Language Teachers

- 7 Sharing: Open Educational Resources for Language Teachers

- 8 Online Communities of Practice: A Professional Development Tool for Language Educators

- 9 Theoretical Approaches and Research-Based Pedagogies for Online Teaching

- 10 Developing Online Teaching Skills: The DOTS Project

- 11 Using DOTS Materials for the Professional Development of English Teachers in Turkey: Teachers’ Views

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Developing Online Language Teaching by Regine Hampel, U. Stickler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Teacher Training. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.