- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Baby Boomers and Generational Conflict

About this book

The dominant cultural script is that the Baby Boomers have 'had it all', thereby depriving younger generations of the opportunity to create a life for themselves. Bristow provides a critical account of this discourse by locating the problematisation of the Baby Boomers within a wider ambivalence about the legacy of the Sixties.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Baby Boomers and Generational Conflict by Jennie Bristow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Politique sociale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Sociology of Generations

1

Introduction

In recent years, the Baby Boomer generation has become the subject of numerous articles, books and policy debates. The Boomers of our present-day imagination are personified, not by the earnest players of Trivial Pursuit, who ‘grew up with the Beatles and television’ and ‘could tell you how many series of Monty Python were made, which British folk singer had a guitar labelled “This machine kills”, and Kookie Byrnes’s trademark act of vanity on 77 Sunset Strip’ (Turner, 1986a, Times). They are personified by the degenerate hedonists Patsy and Edina in the cult BBC sitcom Absolutely Fabulous [Ab Fab]; the ‘stroppy, cocky, randy epitome of rebellious Sixties youth’ Mick Jagger who, at 65, was still staging sell-out tours (Morrison, 2008, Times); Tony Blair, the prime minister who, when he was popular, brought us ‘Cool Britannia’ and when he wasn’t, the Iraq war; and Bill Clinton, the US President sandwiched between two generations of George Bushes, who charmed and scandalised in equal measure.

On an everyday level, the Boomers appear to be embodied in a ‘silver tsunami’ (Bone, 2007, Times; Goldenberg, 2007, Guardian) of ‘young olds’ who have just started retiring and threaten to live forever, allegedly sending the country into never-ending debt as it struggles to pay for spiralling costs of pensions, health and social care, and using their considerable voting and purchasing power to skew markets and public policy around their own interests. They are the ‘Sixties generation’ (Edmunds and Turner, 2002a, p. vii) who promised personal liberation, cultural transformation, and eternal youth – until they hit retirement, when everybody realised what a mess they had made of everything, and what an enormous cohort they actually were.

So the story goes. But this story is a one-sided one, at best.

The upsurge of interest in the Baby Boomers in recent years relies on a narrative that holds this generation responsible for an extraordinary range of social problems. The Conservative politician David Willetts, then Minister of State for Universities and Science, in 2010 accused the Baby Boomers of throwing a 50-year-long party for which ‘the bills are coming in; and it is the younger generation who will pay them’ (Willetts, 2010a, p. xv). These ‘future costs’ include ‘the cost of climate change, the cost of investing in the infrastructure our economy will need if we are to prosper, and the cost of paying pensions when the big boomer cohort retires, on top of the cost of servicing the debt the government has built up’. But for Willetts, the Boomers’ failure goes way beyond poor financial management: ‘The charge is that the boomers have been guilty of a monumental failure to protect the interests of future generations’.

At the other end of the political spectrum, the left-leaning writer Francis Beckett, editor of the University of the Third Age’s (U3A) magazine Third Age Matters, accuses the Sixties generation of selling out on the radicalism of that era. ‘What began as the most radical-sounding generation for half a century turned into a random collection of youthful style gurus who thought the revolution was about fashion; sharp-toothed entrepreneurs and management consultants who believed revolution meant new ways of selling things; and Thatcherites, who thought freedom meant free markets, not free people’, he declares bitterly. ‘At last it decayed into New Labour, which had no idea what either revolution or freedom meant, but rather liked the sound of the words’ (Beckett, 2010a, p. ix). While Beckett’s appreciation of Sixties radicalism is clearly very different from that of Willetts, the central charge he levels against the Baby Boomers is the same:

The baby boomers saw themselves as pioneers of a new world – freer, fresher, fairer and infinitely more fun. But they were wrong. The world they made for their children to live in is a far harsher one than the world they inherited. (Beckett, 2010a, p. ix)

I began researching on the question of how the Baby Boomers became constructed as a social problem in Britain in the autumn of 2010. In this year, three high-profile British books were published that, as Machell and Lewy (2010) report in the Times (London), showed that publishers have ‘cashed in’ on the current ‘war between the generations’ (Kaletsky, 2010, Times). These were, listed here in order of their significance to the debate:

- The Pinch: How the baby boomers took their children’s future – and why they should give it back, by David Willetts.

- Jilted Generation: How Britain has bankrupted its youth, by Ed Howker and Shiv Malik.

- What Did the Baby Boomers Ever Do For Us? Why the children of the sixties lived the dream and failed the future, by Francis Beckett.

A further pamphlet – It’s All Their Fault, by Neil Boorman, described by Machell and Lewy as ‘[a]s much a screed as analysis’ – gained some attention by virtue of being published at the same time. All four books ‘seek to explain the political, social and economic factors that have combined to create the unusual (and for many, difficult) situation where parents seem to have had it better than their children. Some try to apportion blame’ (Machell and Lewy, 2010, Times).

At this time, I was struck by a number of elements in the ‘Baby Boomer problem’ as it immediately appeared. First was the range of social problems for which the Boomers were held responsible: from environmental destruction to the financial crisis to sexual licence and rampant materialism, as indicated in the quotes by Willetts (2010a) and Beckett (2010a) above.

Second was the consensus about the extent to which the Boomers were to blame – a consensus stretching across the political spectrum, and also across the generations writing about the Boomers. Thus Willetts and Beckett both situate themselves clearly within the Baby Boomer generation, and offer their critiques as a form of generational mea culpa, while Howker and Malik, who are journalists for national newspapers and periodicals, situate themselves as members of the ‘jilted generation’ whose plight they attempt to articulate: ‘They are both 29 and live in London’ (Howker and Malik, 2010a, front matter). For these authors too, the ‘sheer size’ of the Baby Boomer generation ‘has some wide-ranging implications for our society’: as resource pressures intensify, ‘[t]he generation who will bail Britain out can’t quite get started’ in the labour market or on the property ladder, which in turn indicates a fundamental problem with ‘the mechanism by which our society considers the past and the future – our relationship with time’ (Howker and Malik, 2010a, pp. 6, 15, 14). In the present discourse, the notion that the Boomers somehow ‘took their children’s future’ (Willetts, 2010a) seems to be shared across the generations.

The third element that struck me was the potential consequence of what appeared to be a deliberate strategy to articulate (and indeed, foment) a conflict between generations who are still very much living, related to one another both through kinship relations and wider social ties. ‘If circumstances get worse, people will begin looking for simple shapes’, Howker and Malik (2010a, p. 15) warn. ‘They will start to seek out a narrative, any narrative. And then people will find someone to blame.’

This book attempts to engage with ‘generationalism’, a term used to describe ‘the systematic appeal to the concept of generation in narrating the social and political’ (White, 2013, p. 216), as a way of explaining political and cultural shifts. White draws out some of the tensions within the development of generation as ‘an emergent master-narrative on which actors of quite different persuasions converge as they seek to reshape prevalent conceptions of obligation, collective action and community’ (p. 217).

Through an analysis of how the cultural script of the Baby Boomer problem has developed over the post-war period, and particularly from the mid-1980s to the present day, this book reveals how ‘Boomer blaming’ has been mobilised within the political and cultural elite to explain problems that have their origin, not in generational or demographic shifts, but in wider social and historical factors. The primary impact of ‘generationalism’ is to mystify the causes of social problems, and to set in motion the very thing that Howker and Malik warn against: a simplistic narrative that relies on blaming older people for the myriad problems of the present day.

When a narrative of ‘Boomer blaming’ takes hold within the elite, practical consequences are likely to follow. These include policies designed to penalise the older generations for the alleged benefit of the younger generations, and, more insidiously, encourage people to think at a ‘common sense’ level that their Baby Boomer parents, colleagues, or acquaintances are the cause of their own economic or existential difficulties. The Baby Boomers, after all, are not embodied only in political leaders or cultural caricatures, but in real people with whom we share our everyday lives.

The fourth element of the Baby Boomer problem is the contradictory character of claimsmaking with regard to why the Boomers allegedly constitute a social problem in the present day. By analysing how the cultural script of this problem has developed, we can see that, despite the extraordinary level of consensus that the Boomers constitute a social problem, explanations about who, exactly, the Boomers are, and why, exactly, they are a problem, vary widely and change over time. This indicates that the social problem of the Baby Boomer is not an objective fact that has only recently been discovered and articulated, but rather that generational explanations have come to be mapped onto pre-existing social problems, which have their origins somewhere other than within the generations.

Defining the Baby Boomers

Perhaps the starkest illustration of the contradictions within the cultural script is the extent to which claimsmakers – those who make claims about how and why the Baby Boomers are a problem – differ in their definitions of what the Baby Boomer generation actually is.

The very label ‘Baby Boomers’ carries with it a wealth of meaning. At its most basic demographic level, it relates to a phenomenon that took place after the Second World War, where many countries in the Western world experienced a surge in the birth rate. The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘baby boomer’ as ‘a person born during the baby boom following the Second World War’, and dates the use of this term to 1970, with a reference by the Washington Post to ‘[t]he baby boomers of the Eisenhower decade’ (OED Online, 2014). In historical terms, the concept of the ‘baby boomer’ also relates to a time of economic ‘boom’ in the USA and, to a more limited extent, in the UK (Marwick, 2003; Sandbrook, 2005). When members of the Baby Boomer cohort were in their infancy, they were also discussed as ‘the post-second world war “baby bulge”’ (Toynbee, 1998, 2014, Guardian); that ‘Baby Boom’ became the accepted definition reflects the twin historical and demographic characteristic ascribed to this cohort.

Interest in the Baby Boomers is an international phenomenon, reflected in the academic and grey literature of North America, Europe and Australia. This reflects a combination of demographic, social, cultural and political trends. But there is a big gap between the demographic existence of the Baby Boomer cohort, and the way the Baby Boomer generation is described and discussed in Britain through the contemporary cultural script. Thus, in the polemical grey literature recently published on the Baby Boomer problem in the UK, the precise dates ascribed to the Baby Boomer cohort vary according to the date periods preferred by those who are writing about them.

Willetts (2010a, p. xv) defines the ‘boomers’ as ‘roughly those born between 1945 and 1965’. This definition is broadly shared by Boorman (2010, pp. 11–13), who sees his book in even broader terms, as ‘a chance for those born in the Seventies and Eighties to respond to the chaos caused by those born in the Forties and Fifties’. A project launched by the Social Research Institute of the UK polling company Ipsos MORI following the publication of Willetts’s The Pinch defines the Baby Boomers in 2010 as ‘all adults aged 45–65’ (Ipsos MORI, n.d.).

However, this ‘wide’ definition of the Baby Boomers, encompassing a cohort born over a period of 20 years, is challenged by other writers on the Baby Boomer problem. Beckett (2010a, p. vii) argues that there were in fact two baby booms in the post-war period, and that ‘[t]he classic baby boomers, born between 1945 and 1955, were a completely different sort of generation from those born at the start of the sixties.’ Howker and Malik (2010a) distinguish between the ‘“first-wave” baby boom’, which ‘occurred in all Western countries following the end of the Second World War’, and the ‘second-wave baby boom’ in Britain:

In America, that [post-war baby] boom carried on for the next twenty years, but in Britain it slowed down, rising again only between the years 1956 and 1965 in the ‘second-wave baby boom’. Since then some have died and others have migrated, but today in total there are 16.7 million baby boomers in Britain. (Howker and Malik, 2010a, pp. 4–5)

Ian Jack (2011, Guardian) notes that the ‘baby boomer generation’ is ‘a term borrowed from America and quite wrongly applied to the post-war pattern of British birth rates. (Not until 1975 were as few babies born as in 1945; more British babies were born between 1956 and 1966 than in the so-called boomer decade of 1945 to 1955.)’ The US Census Bureau in fact defines the American post-war ‘baby boom’ as including ‘people born from mid-1946 to 1964’ (Werner, 2011).

The historian Jean-François Sirinelli (2003, title page, p. 9), meanwhile, defines the French Baby Boomers in both historical and demographic terms as encompassing 24 years (‘Une génération, 1945–1969’), and suggests that an important factor in their significance was the ‘coup de jeune’ effected by the existence of a relatively large proportion of young people at a particular historical moment.

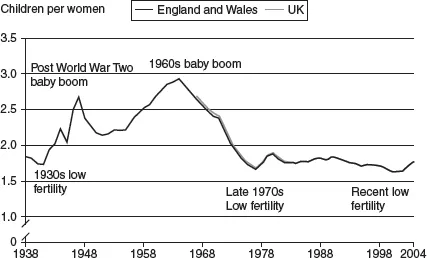

Figure 1.1 illustrates the character of the two British ‘Baby Booms’, where a distinction is made between the ‘Post World War Two baby boom’ and the more sustained ‘1960s baby boom’. Here, the fall in the fertility rate between 1950 and 1955 is very apparent, confirming the arguments put forward by Howker and Malik (2010a) and Jack (2011).

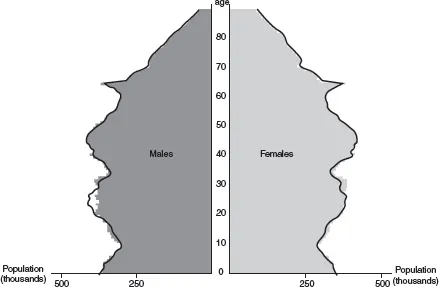

Figure 1.2 illustrates the effect of these peaks and troughs in the birth rate on the demographic situation in England and Wales today, where the Baby Boomers now form a ‘spike’ in the proportion of people aged around 65, and a ‘bulge’ in the proportion of people between the ages of about 40 and 50. It is this age distribution, between the proportion of the population of working age and those of retirement age, which forms the basis of current anxieties about ‘ageing societies’, discussed in Part II of this book. However, for the purpose of defining the Baby Boomer cohort, it is worth indicating that ‘[t]he classic baby boomers, born between 1945 and 1955’ (Beckett, 2010a, p. vii) form a relatively small proportion of the retired population overall.

Figure 1.1 Total fertility rate, 1938–2004

Source: Office for National Statistics, General Register Office for Scotland, Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, in Chamberlain and Gill, 2005, p. 76. Licensed under the Open Government Licence v.2.0.

Figure 1.2 Population pyramid for England and Wales, mid-2011

Note: Census-based estimates (bars) and mid-2011 rolled-forward estimates (line).

Source: Office for National Statistics, 2013. Licensed under the Open Government Licence v.2.0.

The disagreements over defining the British Baby Boomers as a demographic cohort, and the disparities between the demographic situation in Britain and that in North America, reflect a wider conversation about the significance of this cohort, and the way ideas about its significance have changed over time. A useful discussion of this point is provided by Falkingham (1997), who notes that there were two ‘baby booms’ in Britain, in comparison to the more ‘pronounced’ rises in the crude birth rate that took place in the Australia, Canada, France and USA. Furthermore, Falkingham explains that the actual numbers of babies born in these peaks in the birth rate were relatively smaller:

For example, for the first 50 years of this century Canada averaged around 250,000 births per annum, with only slight variation from year to year. However, from 1952 to 1965 between 400,000 and 500,000 children were born every year – nearly twice the previous rate. For every two children born previously there were now at least three. According to the 1966 Census, one-third of the entire population of Canada had been born in the preceding 15 years.

In contrast, whilst the number of babies born in the UK in the years 1947 and 1964 excee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Part I The Sociology of Generations

- Part II The Construction of the Baby Boomers as a Social Problem in Britain

- Appendix: Study Design

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index