eBook - ePub

The Criminal Act

The Role and Influence of Routine Activity Theory

M. Andresen,G. Farrell

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Criminal Act

The Role and Influence of Routine Activity Theory

M. Andresen,G. Farrell

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume provides a unique collection of essays in honour of the work of Marcus Felson and his notable contribution to routine activity theory, environmental criminology and the discipline more broadly. Chapter 5 of this book is open access under a CC BY license.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Criminal Act an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Criminal Act by M. Andresen,G. Farrell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Criminologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Sciences socialesSubtopic

Criminologie1

Introduction

Martin A. Andresen and Graham Farrell

This book is a Festschrift honouring the work of Marcus Felson. The 14 studies it contains were specially commissioned. That we were able to attract such a fine set of scholars as contributors is a compelling tribute to Marcus Felson’s work and influence, and we apologize to the many scholars who we know would have been willing to contribute had there been further capacity on our part. The prompt and expert manner in which the authors completed their work made our task as editors an easy one. The book pays tribute via its substantive original contribution to knowledge. This means that the audience for this book should extend far beyond those wishing to learn a little about the man himself.

The chapter authors are either close colleagues, often co-authors, or students of Marcus Felson, and in so being represent some of the leading proponents of the routine activities approach. Fittingly, the title of Chapter 2 by John Eck and Tamara Madensen offers the acronym MARCUS to encapsulate the Felsonian approach to theory building. John Eck has, alongside his many other contributions, been responsible for key developments within the routine activities perspective, including place managers, super controllers, and the ubiquitous crime triangle. He has a long-standing collaboration with Madensen, whose work on crowd control leads that field. Combining the wit and insight that characterizes the work of Marcus Felson, they use the analogy of tinker toys to explain the development of Routine Activity Theory and how “playing” with a theory can provide useful insights.

D. Kim Rossmo and Lucia Summers apply Routine Activity Theory in the context of a criminal investigation in Chapter 3. Rossmo is a world leader in the field of geographic profiling, which draws heavily on concepts and theory relating to routine activities, and which marries well with Summers’ work on repeat victimization and other areas. Combining this expertise they show how routine activities can help understand the spatial-temporal patterns of a particular crime in ways that should inform police investigation.

Chapter 4 by Gisela Bichler and Aili Malm is a particularly innovative analysis of transnational crime from a routine activities perspective. They show how legal, marginal, and illicit markets are connected on a global scale. These authors are at the cutting edge of work on network analysis and the identification of its practical, useful, implications by integrating it with the routine activities approach.

Chapters 5 and 6 both relate to the major drops in crime that have been experienced in many advanced countries over the last two decades. There is symmetry here with the fact that the routine activities perspective was originally developed by Marcus Felson to explain why crime had previously been increasing for several decades. In Chapter 5, Nick Tilley, Graham Farrell, and Ronald V. Clarke argue that target suitability, a cornerstone of Routine Activity Theory, has been critical. They suggest that improved security which reduced target suitability has underpinned much of the crime decline and provides evidence relating to household burglary. Tilley is an internationally renowned expert in policing and evaluation among other areas. Clarke is probably Felson’s most frequent co-author, and they have published many influential studies combining elements of routine activities, situational crime prevention, and rational choice.

The routine activities perspective has always been influential in work on repeat victimization, which has been pioneered by Ken Pease. In Chapter 6, Dainis Ignatans and Ken Pease further establish the important role of repeat victimization in the crime drop. They show how a relatively small percentage of victims account for the greatest declines in crime since the 1990s, but that, perhaps more importantly for crime policy, crime remains heavily skewed against those people and places that are most victimized.

The author of Chapter 7 is “Marcus’ little brother,” Richard Felson. Richie does not need reflected familiar glory as he is a renowned scholar and recently appointed Fellow of the American Society of Criminology. So we are immensely grateful that he provides a compelling chapter examining the overlap between his own work on social psychology and the routine activities perspective as they relate to violence. He has some particularly dry comments on sibling violence, and for those who do not know the Felson brothers, Richie’s humour is less indirect in his letter in the final chapter.

Rachel Santos, a leading light in crime analysis and co-author with Felson of the fourth edition of Crime and Everyday Life, is the author of Chapter 8. She makes a compelling case that Felson could claim to be one of the most important influences upon the field of crime analysis.

Offender mobility is an enduring theme of the routine activities perspective. In an analysis of offender mobility over the course of the day, Kate Bowers and Shane Johnson, in Chapter 9, show how this can impact the spatial distribution of offending. Their evidence suggests that night-time burglaries are more likely undertaken by “insiders” who live close by, whereas daytime burglaries are more likely undertaken by “outsiders” from outside the immediate neighbourhood. Bowers and Johnson are leaders in the field of Crime Science, which is strongly linked to the routine activities perspective. In Chapter 10, Patricia and Paul Brantingham discuss how changes in our environment, a key component of Routine Activity Theory, may be used to understand crime patterns. They discuss how the concepts of Routine Activity Theory may be used to understand Internet-related crime.

Sharon Chamard, former doctoral student of Felson, shows how Routine Activity Theory can be used to understand the location of homeless encampment in Chapter 11. Johannes Knutsson, professor of police research at the Police University College in Norway, analyses bicycle theft data from Sweden in Chapter 12. He shows how climate affects routine activities that in turn alter criminal opportunities. AM Lemieux, also a former doctoral student of Felson, employs time-use data to calculate time-adjusted rates of violence in Chapter 13. He shows that, relative to time spent in different places, the home is the safest place, whereas the street is the most dangerous, and particularly public transportation areas. Capable guardians are an important aspect of Routine Activity Theory and are investigated by Richard Wortley in Chapter 14. He finds that guardians become capable when they consider safety from retaliation, and less capable as the number of offenders increases. Among Wortley’s many contributions is his pioneering work on situational precipitators and the way that many everyday designs can trigger or generate crimes of different types. The last of the original studies is Chapter 15 by George Rengert, Brian Lockwood, and Elizabeth Groff who originate from Temple University, a key source of much original thinking relating to the routine activities approach. They consider suitable targets and capable guardians in the context of burglary and the race of the offender, finding that the race of the offender has implications for the understanding of notions of suitable targets and capable guardianship, depending on the type of neighbourhood.

The last chapter in this volume, Chapter 16, is a collection of letters addressed to Marcus Felson. Rather than writing about the importance and influence of Marcus here, we thought it would be best for those who know him in the roles of colleague, supervisor, and teacher to say this in their own words. We again draw your attention to the letter from Marcus’ brother Richard, whose account of some of Marcus’ childhood is particularly insightful.

The undertaking of this volume of essays in honour of Marcus Felson was truly a pleasure. And so, lastly, we thank Marcus for his inspirational work and generous nature that made it so easy to bring this collection together.

2

Meaningfully and Artfully Reinterpreting Crime for Useful Science: An Essay on the Value of Building with Simple Theory

John E. Eck and Tamara D. Madensen

Theories and toys

Theories are toys. Both toys and theories are abstractions of a far more complex reality. Just as toy manipulation helps infants, children, and adults learn about the world, theory manipulation serves the same purpose for researchers and practitioners. So, it is no coincidence that we use similar criteria for judging the adequacy of toys and theories.

One criterion is how well a toy, or theory, mimics the real world. Of course, the adequacy of this mimicry depends on the senses being used and the purposes to which the toy or theory is being put to use. There are stuffed animals that look like the actual creatures, but are not pleasurable to cuddle, and barely recognizable stuffed animals that children love to hold. The realistic toy may be useful for educating a child about the characteristics of the real beast, while the pleasurable toy may be better for providing comfort. Similarly, some theories provide practical frameworks that explain a variety of real-world processes, while others offer more abstract depictions that inspire reflective thinking about common observations.

Another attribute is the degree to which the toy or theory provides insight into the world. Construction toys can be useful for teaching how things can be assembled, and puzzle-based toys can teach translatable problem-solving skills. Likewise, theories can suggest new avenues of inquiry and subsequently generate new knowledge. For example, computer simulations based on theories can reveal otherwise hidden processes (for example, emergence of macro phenomena from uncoordinated micro-entity interactions) (Eck & Liu, 2008). Insights, including predictions, gained from playing with toys or theories can be extended to the real world. Failure of these insights suggests that the toy or theory is inadequate. Thus, both toys and theories can be judged by their ability to teach us about the world through falsification: a third criterion for judging toys and theories.

Many types of theories are used to help us understand crime and criminality. They can be arrayed on a continuum from being Furbielike to Tinkertoy-like. Furbies are highly complex toys. They are electronic robots that resemble animal-like creatures. Furbies initially speak “Furbish” – a fake language – but the toys are designed to use more English words and phrases over time. This gives the impression that the Furbie is learning English as it interacts with its user (and with other Furbies through an infrared port located between their eyes). The toy’s design evolved to display even greater complexity, eventually demonstrating intricate facial movements and voice recognition. This was a highly popular toy, particularly at the time of its initial release. “Over 40 million Furbies were sold during the three years of its original production, with 1.8 million sold in 1998, and 14 million in 1999. Its speaking capabilities were translated into 24 languages” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Furby, 2 December 2013).

In contrast, Tinkertoys are distinctly simple-looking toys. Initially made of wood, Tinkertoy sets include just a few types of pieces, including small wooden spools with holes drilled into the centre and perimeter, and short pointed sticks that fit into these holes. The spool hole placements are based on the Pythagorean theorem and allow users to create 45–45–90 right triangles. As such, Tinkertoys can be used to build simple shapes, such as a triangle or square. However, these basic construction pieces can also be used to build highly complex construction projects. “Tinkertoys have been used to create surprisingly complex machines, including Danny Hillis’s tic-tac-toe-playing computer (now in the collection of the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California) and a robot at Cornell University in 1998” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinkertoy, 2 December 2013).

Furbie theories, like their toy’s namesake, tend to have outward characteristics that make them highly appealing. Furbies are furry, have large eyes, and look cute. They are also internally complex, comprising many interconnected components. And they promise a great deal, just as the advertisements for Furbies suggested that children would find them engrossing. However, as one of us found, when his daughter was given a Furbie at Christmas, the toy became uninteresting quickly. In short, it failed at its main task.

Tinkertoy theories are outwardly simple. At first blush, one might dismiss them as being trivial and obvious, or, in the case of a theory, tautological. They have few parts and simple connections. Tinkertoy theories, however, can be manipulated in numerous ways to gain understanding of a very diverse and complex set of human behaviours. Tinkertoys and other toys with similar characteristics encourage years of exploration. Further, as the above-mentioned Wikipedia quote points out, the few simple components can be used to create incredibly complex phenomena. The same is true with Tinkertoy theories.

In this chapter, we will take a particular Tinkertoy theory, Routine Activity Theory, and illustrate why it is so useful. Using the Tinkertoy analogy, we will illustrate its evolution. We will then speculate on future elaborations that may further expand its utility. We conclude by advocating for a specific use of theory we refer to as “marcusing.”

Evolving Routine Activity Theory

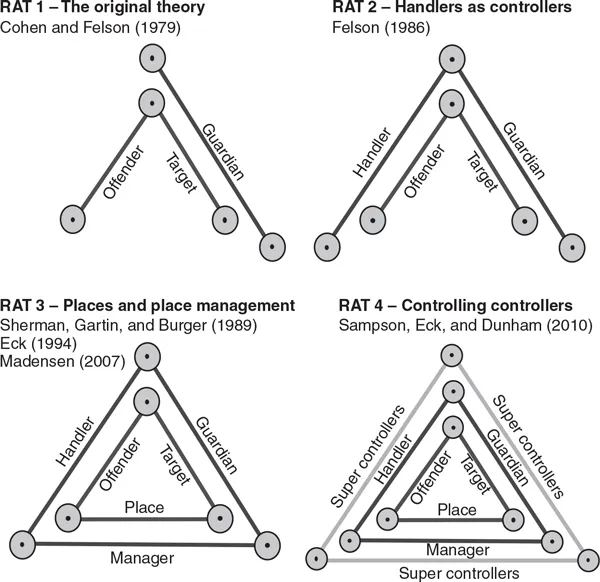

Routine Activity Theory is a Tinkertoy theory. The original version of Routine Activity Theory (RAT 1) contained four elements: the offender, who is motivated to commit the crime; the target (a human victim, animal, or thing), which is the focus of the offender’s predation; a guardian, who tries to protect the target from the offender; and a spatio-temporal routine that brings the first three elements together or causes them to diverge. When common routines bring offenders into contact with targets, while taking guardians elsewhere, crime is likely (Cohen & Felson, 1979). The top left panel in Figure 2.1 illustrates the first three components, that is, the offender, target, and guardian. It shows these elements at the point in their routines where all converge. Despite the presence of an offender, crime is unlikely due to the presence of a controller: the guardian.

In 1986, Felson elaborated on this basic theory (RAT 2 in Figure 2.1). Drawing on earlier work by Travis Hirschi (1969), Felson added another controller: the handler. Handlers are not particularly concerned about targets. They are concerned about keeping potential offenders from getting into trouble. They use social and emotional bonds for this purpose. Consequently, when an effective handler is present, the potential offender will not commit a crime for fear of losing respect, emotional support, or other related personal connections.

Figure 2.1 The...

Table of contents

Citation styles for The Criminal Act

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2015). The Criminal Act ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3489315/the-criminal-act-the-role-and-influence-of-routine-activity-theory-pdf (Original work published 2015)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2015) 2015. The Criminal Act. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://www.perlego.com/book/3489315/the-criminal-act-the-role-and-influence-of-routine-activity-theory-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2015) The Criminal Act. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3489315/the-criminal-act-the-role-and-influence-of-routine-activity-theory-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. The Criminal Act. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.