Crowdfunding is a new phenomenon which gives people (the crowd) the opportunity to fund a project or a business idea they share an interest in using online platforms. Crowdfunding can take several forms and the aim of the book is deepening the understanding of a specific category of crowdfunding, namely financial return crowdfunding, which includes both peer-to-peer (P2P) lending and equity crowdfunding and that reveals itself as an extant, interesting and challenging topic. The theory to which financial return crowdfunding is most closely related is that of asymmetric information, which helps explain the existence of financial institutions because they reduce market imperfections (market failures), consequently avoiding defaults and enabling the transfer of money within the financial system, which is of critical importance to economic development and growth. The theory of asymmetric information also relates to another topic dealt with in the book, that of the financing gap faced by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

We believe that financial return crowdfunding may play an important role in backing firms and projects that would not be funded or only partially financed in traditional ways, that is, through the banking channel or financial markets, particularly in the case of SMEs. This book thus investigates whether financial return crowdfunding is capable of either reducing the funding gap of SMEs and becoming an alternative or a complementary funding channel to traditional sources of capital for those firms. In this context, policymakers play an important role by introducing adequate rules to favour financing for SMEs on one hand and protect investors on the other. Crowdfunding was born in the US and differs from the European approach in many aspects, the most evident being the advance in regulation on the part of the US. It is recognised that crowdfunding, and financial return crowdfunding in particular, should be a regulated activity because of the potential risks it carries. Focusing on the European level, regulation should be homogeneous across all European countries, to avoid regulatory arbitrage and differences in investor protection across countries. Because of the variety of business models, and the novelty of crowdfunding, it is indeed not clear which EU legislation is applicable, or potentially applicable, and how it should be applied.

Given these premises, it is clear that the analysis must involve experts in different disciplines, specifically management, finance and law, to deal with the main aspects related to crowdfunding.

The first two chapters form a basis for the analysis of financial return crowdfunding. Chap. 2 by Flavio Pichler and Ilaria Tezza introduces, defines and conceptualises the phenomenon that is named “crowdfunding.” It also presents a classification of the types of crowdfunding and explores their main features. Further, it investigates the academic literature on crowdfunding that, although rapidly growing, is still in its infancy, to explore the streams of research on this particular funding model and the methodology that is typically used to assess the phenomenon. Chap. 3 by Federico Brunetti depicts the role played by the Web 2.0 technology in fostering the development of crowdfunding. The general features of Web 2.0 as a communication and interaction environment, both at an individual and a collective level, along with the features that are most relevant to crowdfunding will be considered.

The next two chapters concern P2P lending, which is one of the two categories that make up financial return crowdfunding. Chap. 4 by Roberto Bottiglia highlights the competitive frontiers of crowdfunding in terms of both potential clients and likely competitors. The former consists mainly of SMEs and other public and/or private entities performing an economic activity; the latter relates to retail banks and other non-bank financial institutions that provide firms with funding. It is also important to determine which factors foster the success of P2P lending crowdfunding the most.

Chap. 5 by Giuliana Borello investigates the business model of a sample of European P2P lending platforms. The analysis aims at identifying the specific characteristics of this form of crowdfunding that enables it to become an alternative or complementary source of capital for SMEs.

The two chapters that follow deal with the other category of financial return crowdfunding, that of equity crowdfunding. Chap. 6 is by Vincenzo Capizzi and Emanuele Maria Carluccio explores the role of seed financing from venture capital and private equity as equity crowdfunding becomes more important. Platforms will indeed have to cope with collective-action problems, since crowd-investors have neither the ability nor the incentive to devote substantial resources to the sort of due diligence undertaken by venture capital and private equity funds. Chap. 7 by Veronica De Crescenzo takes on the business models of equity crowdfunding platforms with a twofold objective. It first aims at identifying the main features of platforms, target companies and investors. Second, it attempts to point out the key success factors of funding rounds posted on a sample of European equity crowdfunding platforms.

Finally, given the risks that pledgers/investors to a crowdfunding campaign face, the role of regulation should be considered. Chap. 8 by Paolo Butturini gives an insight into the regulation of crowdfunding in Europe, both at a domestic and a supranational level. Indeed, some European countries have already set up specific rules relating to financial return crowdfunding; however, the definition and implementation of a set of agreed, common rules at the European level are still in their infancy.

2.1 Introduction

Crowdfunding is a relatively new funding practice through which people, often living in different geographical areas, provide (small) amounts of money to a project they are interested in. Money is raised either directly or through online platforms using Web 2.0 technologies. The precise factors that lead to the boom in crowdfunding remain unclear. However, two driving features can be identified: the structural and the contingent. The former is represented by the availability of web technology and the latter by ‘the credit crunch’ that occurred after the 2007–2008 global financial crisis (Kirby and Worner 2014, p. 12).

The aim of this chapter is to shed light on this phenomenon from several perspectives. We will first recount a short history of crowdfunding, from its origins to its most recent campaigns. We will also provide a detailed definition and classification of crowdfunding types, examine the motivations for participation of both the funders and the fundraisers, and highlight the risks associated with this source of funding. In addition, we will review studies that have attempted to identify the features of a successful crowdfunding campaign and the presence of herding by funders. This will provide us the opportunity to highlight further research streams.

The chapter is organised as follows: the next section presents a short history of crowdfunding and provides a definition and a classification of crowdfunding models. This section also presents reflections on the benefits and risks posed by crowdfunding, and discusses data on the phenomenon. Sect. 2.3 presents the literature review, and Sect. 2.4 suggests future directions for research.

2.2 What Is Crowdfunding?

Although crowdfunding may appear to be a new phenomenon, in fact, it is not. Artists such as Beethoven and Mozart financed concerts and the publication of manuscripts using individual donations (Hemer et al. 2011). In 1876, the Statue of Liberty was financed through crowdfunding, with citizens of France and the United States conducting initiatives to raise money—France for the statue and the US for the pedestal (Best and Neiss 2014). More recently, one of the most well-known successful crowdfunding campaigns was that of the UK rock band Marillion. In 1997, this band raised $60,000 in donations from their fans to finance their North American tour (Vassallo 2014). Other examples of successful campaigns are those of the Pebble Smartwatch and the movie Veronica Mars, both of which were funded on Kickstarter. In 2012, the Pebble campaign raised $10,266,845 from 68,929 people1; in 2013, the Veronica Mars campaign raised $5,702,153 from 91,585 investors.2 In November 2014, the Caterham Formula One racing team financed its participation in the last Grand Prix in Abu Dhabi through the crowdfunding platform Crowdcube, raising £2,354,389 from 6467 investors.3 What distinguishes old from modern crowdfunding campaigns is the presence of the web: nowadays, money is given to ideas and projects through online platforms.

The recent exponential growth of crowdfunding is mainly due to the technological innovation of Web 2.0 and the 2007–2008 global financial crisis. In the wake of O’Reilly’s (

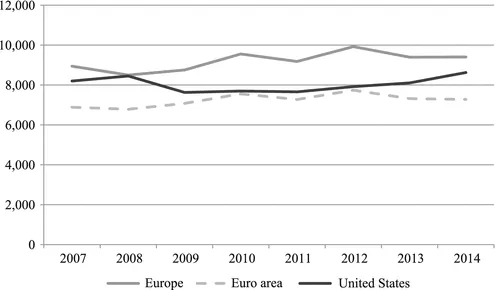

2007) seminal paper, we define Web 2.0 as all the websites and applications that allow internet users to create and share online any type of information or material, that is, through social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, as well as blogs and sites such as Wikipedia. The role of the financial crisis is also important. It is commonly recognised that since the financial crisis broke out in 2007 (and even more seriously, in 2008 after the collapse of the US bank Lehman Brothers), bank credit has almost ceased, primarily in Europe and North America (see Fig.

2.1). As such, financing for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and individuals decreased significantly during the crisis, thus creating a gap for crowdfunding as an alternative method for raising money (Dapp

2013, p. 2; Hagedorn and Pinkwart

2013,

2016). Nevertheless, as Fig.

2.1 demonstrates, bank credit has begun to recover, creating the opportunity for crowdfunding to become a complementary source of capital for SMEs and individuals, rather than being an alternative to bank credit.

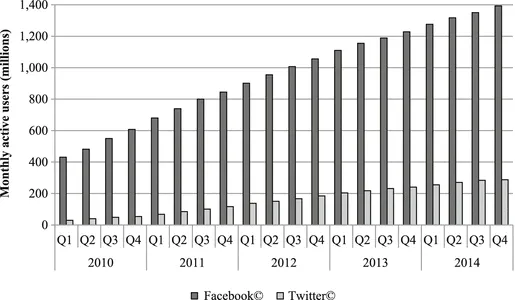

4 The importance of the Web 2.0 can be demonstrated by examining the number of worldwide monthly active users on Facebook and Twitter between 2010 and 2014. We selected these two social networks as a proxy of the importance of the Web 2.0 because they are the two most well-known social networks (Fig.

2.2).

5 The number of Facebook and Twitter monthly active users increased by 223 % and 860 % respectively in the 2010–2014 period.

The term ‘crowdfunding’ originates from the term ‘crowdsourcing’, which is defined as ‘the act of a company or institution taking a function once performed by employees and outsourcing it to an undefined (and generally large) network of people in the form of an open call’ (Howe 2006a). Kleemann et al. (2008, p. 6) extend this initial definition by introducing the role of the internet (given that the ‘open call’ is now made over the internet), and explicitly state that the contribution of the crowd should be made to produce or sell the product (‘Crowdsourcing […] takes place when a […] firm outsources specific tasks essential for the making or sale of its product to the general public (the crowd) in the form of an open call over the internet, with the intention of animating individuals to make a contribution to the firm’s production process’). Thus, in general terms, ...