eBook - ePub

Marketing Big Oil: Brand Lessons from the World's Largest Companies

Brand Lessons from the World's Largest Companies

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marketing Big Oil: Brand Lessons from the World's Largest Companies

Brand Lessons from the World's Largest Companies

About this book

Marketing Big Oil begins with an historical perspective looking at how Big Oil came to be and then analyzes the marketing and corporate branding programs of these oil titans to demonstrate what does and doesn't work, showing us how even the largest companies sometimes fail to get their message across.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marketing Big Oil: Brand Lessons from the World's Largest Companies by M. Robinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

From Standard Oil to Big Oil

1

Big Oil and the Love-Hate Relationship

Abstract: Big Oil is the popular name given to represent the four largest western oil companies, Exxon Mobil, BP, Chevron, and Royal Dutch Shell. These companies have had to endure a poor image with the general public for well over 100 years. They also remain popular targets for investors. This relationship is polarizing. People either love them or hate them. While Big Oil historically sits atop most annual company rankings based on revenues, these companies are ranked towards the middle or end of the pack when ranked on brand value.

Robinson, Mark L. Marketing Big Oil: Brand Lessons from the World’s Largest Companies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137388070.0006.

As far back as most Baby Boomers can remember the oil industry has had a poor brand image. As teenagers, we were exposed to the harsh reality of price shocks while learning to drive a car for the first time during the Arab oil embargo (October 1973 to March 1974). “Gasoline rationing” became part of the lexicon as motorists waited in long lines for a chance to fill up their cars with gasoline. And in December 1978, due to the political and economic upheaval in Iran, motorists around the world once again faced shortages of fuel and rising prices. In the eyes of the public, oil companies were responsible for these shortages and high oil prices. In short, Big Oil owns a poor corporate brand from which it is beginning to recover.

In a recent Gallup organization public opinion survey titled “Americans Rate Computer Industry Best, Oil and Gas Worst,” the oil industry, which includes the largest of the vertically integrated oil companies—Exxon Mobil, BP, Royal Dutch Shell/Shell Oil (U.S.) and Chevron—ranked last out of 25 industries in terms of consumer popularity.1

Why is Big Oil so demonized? The reasons are many. First, motorists pay a price for a product where the economics of oil and gasoline supply and demand aren’t well understood. When gasoline prices rise, typically in tandem with an increase in the price of oil, motorists can’t miss seeing the daily reminder of high retail prices plastered on roadside signage along with the company’s logo at their corner station. High gasoline prices act like a tax on motorists, taking away disposable income that might otherwise be spent on other goods and services. Second, environmental disasters such as BP’s oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010 and the Exxon Valdez grounding and spill in Alaska during March 1989 continue to portray the industry as owning a poor corporate image. Based on the research conducted for this book, this poor image is not entirely due to these actual events—although they do play a role—but rather how poorly the events were handled from a public relations and crisis communications perspective. The inability to strategically manage these events demonstrates that Big Oil is woefully ill-prepared to deal with environmental disasters. Third, Big Oil continues to be a money-making machine which makes these companies attractive to investors, but serves as a painful reminder for consumers of the discrepancy between large company profits and high retail prices.

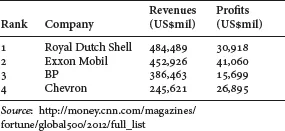

Each year, Fortune magazine issues its Fortune Global 500 annual company rankings. For 2012, Big Oil was ranked as seen in Table 1.1.

TABLE 1.1 Big oil company rankings by revenue

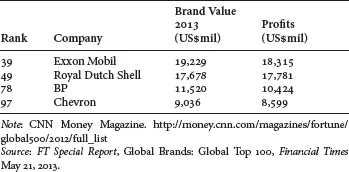

TABLE 1.2 BrandZ’s top 100 global brands (Big Oil)

Contrast the Fortune ranking with that of BrandZ’s Top 100 Global Brands as ranked by brand value and Big Oil is seen in a different perspective as seen in Table 1.2.

In the annual Fortune ranking, Big Oil has continuously ranked at or near the top in terms of revenues and profits; in the BrandZ ranking, oil companies tend to be placed in the middle or towards the end of the pack, while companies like Apple, Google, and Microsoft ranked the highest in brand value. Fourth, consider a recent trip to the gasoline or petrol station. In terms of attractiveness, Big Oil’s retail stations have been an afterthought. The stations can make for an unpleasant customer engagement experience in terms of overall appearance, lighting, and restroom facilities. At times, the benzene fumes coming from the gasoline hose can be overwhelming. The major oil companies need to place more emphasis on their retail operations as they are often the only opportunity the companies have to directly engage with their customers.

Perhaps the most important reason why oil companies operate under an umbrella of negativity is that the industry has failed to educate and connect with the public as to what value they provide to the society. That could change if Big Oil adopted many of the brand building processes and consumer engagement tools being used by today’s innovative companies.

So, why do many people hate the largest oil companies? As former Shell Oil executive John Hofmeister wrote, the primary reason is a fundamentally wrong approach to corporate communication:

Instead of being accessible to the media, many energy companies choose to buy advertising space to tell a guarded version of the truth. Instead of educating consumers on the real risks and real cost of energy, they choose to sponsor cultural and educational television programs. Instead of being on-site to respond to a crisis, they send the lawyers.2

So how did this love-hate relationship with Big Oil get started? It all began with one person and the company he founded: John D. Rockefeller, Sr. and the Standard Oil Company.

Notes

1Gallup organization poll. “Americans Rate Computer Industry Best, Oil and Gas Worst.” (August 16, 2012). Accessed April 11, 2014, http://www.gallup.com/poll/156713/americans-rate-computer-industry-best-oil-gas-worst.aspx

2John Hofmeister. Why We Hate the Oil Companies (Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2006), p. 7.

2

The Oil Refining Era: 1863–1869

Abstract: The Oil Refining era began in Cleveland, Ohio where Standard Oil founder John D. Rockefeller, Sr. formed his company, not to refine gasoline or petrol as it is referred to in other parts of the world, but kerosene. Motor vehicles requiring gasoline would not appear until well into the 20th century. Refining crude oil into kerosene required access to crude oil supplies and access to a transportation method. In these early years of the oil industry, refining companies had to rely on railroads which were continually expanding throughout the United States. Rockefeller made secret deals with the railroads forming what today we would call a cartel between oil refiners and railroads.

Robinson, Mark L. Marketing Big Oil: Brand Lessons from the World’s Largest Companies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137388070.0007.

The history of the oil industry is rife with conflicts, embargoes, economically devastating price swings, and the introduction of “ ‘big business” into the lexicon. It also provides examples of competitive intimidation, secret business arrangements, industrial espionage, and monopolistic activities. These negative images of the oil industry were based on the corporate culture of one entrepreneur and the company he founded in 1870: John D. Rockefeller, Sr. and the Standard Oil Company. As a by-product of industrial consolidation, antitrust legislation, and corporate spinoffs, the siblings of Standard Oil—now known as Big Oil—have unknowingly perpetuated the negative image of their former corporate parent some 140 years later.

The first oil strike

Within a few months following Edwin Drake’s oil strike in Pennsylvania on August 28, 1859, local media began reporting on the infatuation with discoveries of black gold. On November 18, 1859, the Cleveland Dealer newspaper reported “the oil springs of Northern Pennsylvania were attracting considerable speculation” and that there was “quite a rush to the oleaginous locations.”1

Every amateur geologist and prospector descended on these Pennsylvania oil fields in hopes of striking it rich. One of those individuals seeking to make his fortune in oil was John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

Rockefeller was born in Richford, in upstate New York on July 8, 1839. After spending his formative years in New York, the Rockefeller family moved to Strongsville, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland. He entered a professional school where he perfected the practice of single- and double entry bookkeeping along with other skills that would ultimately serve him well in his future businesses. At age 16, Rockefeller landed his first job, working for Hewitt & Tuttle, commission merchants and produce shippers. From there, Rockefeller would quickly learn how to buy and sell commodities giving him valuable insight into his future business: selling refined oil products.

Rockefeller and the beginnings of oil refining

In 1863, Rockefeller, along with business partners Maurice Clark and Samuel Andrews, gained entry into the industry not by exploring, drilling, and producing oil—known as upstream—but by refining it into kerosene (gasoline refining would come many years later). Today, the refining division of large oil companies is called downstream and includes transporting finished gasoline to local area storage tanks, tanker trucks which transport gasoline from storage tanks to underground gasoline holding tanks at the local retail station, and the final sale of gasoline to consumers.

At the time he began his foray into refining, Rockefeller was a commission agent far removed from the producing oil wells. As a middleman, Rockefeller exemplified a new breed of the American entrepreneur, destined to innovate and carve out his or her own niche in the new industrial economy. These entrepreneurs were people who spent their days trading and distributing all types of commodities, mostly food products. Following several years of financial success, the team of Rockefeller, Andrews and Clark formed a new corporate entity: Andrews, Clark & Company and built the first kerosene refinery called the Excelsior Works in The Flats, Cleveland’s emerging industrial area. This previously isolated and unused area would soon become an important hub in local and domestic commerce due to its proximity to the U.S. East Coast via the railroad. Locating the refinery close to the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad gave Rockefeller and his partners an undisputed competitive advantage over other refiners due to their lower transportation costs.

In those early days of the burgeoning oil industry, US$1,000 was the initial financial investment for owning a refinery and the employees to manage and run it. Anyone that could raise the money could soon own their very own refinery even though few business people of the day knew how to run a business much less the basic economic principles of supply and demand. Coupled with large discoveries of oil and undisciplined production levels, the ind...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I From Standard Oil to Big Oil

- Part II Managing the Brand Crisis

- Part III Marketing Strategies and Brand Building

- Part IV Big Oil and the Era of Consumer Engagement

- Part V Concluding Remarks

- Index