- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Violent Women in Contemporary Cinema

About this book

Violent women in cinema pose an exciting challenge to spectators, overturning ideas of 'typical' feminine subjectivity. This book explores the representation of homicidal women in contemporary art and independent cinema. Examining narrative, style and spectatorship, Loreck investigates the power of art cinema to depict transgressive femininity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Violent Women in Contemporary Cinema by Janice Loreck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Horror, Hysteria and Female Malaise: Antichrist

One of the key films to emerge in recent years about women’s violence is Lars von Trier’s controversial tale of marital discord, Antichrist (2009). Premiering at the 62nd Cannes International Film Festival, the film follows an unnamed couple, the Man (Willem Dafoe) and the Woman (Charlotte Gainsbourg), whose infant son, Nic, dies after falling from the high window of his nursery.1 The Woman is so overwhelmed with grief and guilt following the accident that she suffers a nervous breakdown and eventually attacks her husband. Underpinned by the story of a woman’s destabilising emotional malaise, Antichrist recalls several horror films that link women’s violence with madness and maternity, particularly The Brood (David Cronenberg, 1979), À l’intérieur (Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury, 2008), and more recent texts Proxy (Zack Parker, 2013) and The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, 2014).

Antichrist occupies a provocative position in contemporary filmic taste cultures. On one hand, the film contains graphic scenes of violence, mutilation and torture reminiscent of the horror genre: the Woman, for instance, bludgeons her husband’s genitals and mutilates her own with a pair of shears. Combined with the film’s supernatural moments, such sequences reportedly caused Cannes audiences to jeer, laugh and faint during the film’s screening (Badley 2010: 141–2). On the other, however, Antichrist also circulates in ways that characterise it as an art film. The film premiered in competition at the prestigious Cannes Festival, where von Trier had already forged a reputation as an accomplished (albeit polarising) auteur. In 1991, von Trier received three Cannes prizes for his film Europa (1991) and was awarded the Palme d’Or for Dancer in the Dark in 2000. Moreover, due to its combination of ‘low’ culture iconography with a ‘high’ cultural setting (or, more accurately, what is constructed in the discourses of film criticism as ‘high’ and ‘low’), scholars have identified Antichrist as part of the ‘new extremity’: a much-discussed category of art cinema that emerged on the European festival circuit in the late 1990s. In a widely cited article for Artforum, James Quandt coined the term ‘New French Extremity’ to describe ‘a growing vogue for shock tactics in French cinema’ (2004: 127). Quandt pointed in particular to the explicit sexual content and violence in films such as Romance (Catherine Breillat, 1999), Baise-moi (Coralie Trinh Thi and Virginie Despentes, 2000) and Twentynine Palms (Bruno Dumont, 2003) as evidence of a filmmaking trend towards aesthetics borrowed from ‘lower’ cultural forms, particularly pornography and exploitation cinema. Commentators like Tanya Horeck and Tina Kendall have since identified films from outside France, including the works of Ulrich Seidl, Lukas Moodysson, Michael Haneke and Lars von Trier, as also part of the new extremity (2011: 1). Nevertheless, Antichrist was received by many as a text that was incompatible with the Cannes Festival. Shortly after the film’s premiere, for instance, critic Baz Bamigboye confronted von Trier, demanding that he ‘explain and justify’ his work.

Given its art-cinema cachet and its confronting representation of female aggression, Antichrist is an ideal case study with which to begin this book’s investigation of the violent woman in critically distinguished film forms. The depiction of a violent, psychologically disturbed woman in Antichrist recalls the diagnosis of hysteria, a predominantly feminine disease of both the mind and body (although men have been diagnosed as hysterics at various points in medical history). The term originates from the Greek ‘hystera’ meaning ‘uterus’, and one of the earliest accounts of a hysteria-like illness is found in Plato’s Timaeus, in which he describes the disorder as the consequence of a distressed, ‘unfruitful’ uterus that moves around the body, obstructing respiration (2014: 132). Antichrist similarly links the female protagonist’s aggression to her reproductive capacity insofar as her symptoms arise after the death of her only child. With reference to the film’s combined art-horror modality, this chapter therefore examines how the female protagonist is produced as a violent hysteric who turns against her therapist husband.

As I signalled in the Introduction to this book, a focal point for this chapter (and the chapters that follow) is how Antichrist engages with the violent woman’s cultural construction as an enigma. Filmic narratives frequently betray a specifically epistemological anxiety about the violent woman’s subjectivity, positioning her as a ‘problem’ that must be solved: by foregrounding the Woman’s debilitating grief and anxiety, Antichrist certainly constructs a scenario that positions her as a mysterious entity. The commentary around Antichrist at the time of its release, however, shows that critics expected the film to demonstrate some kind of artistic insightfulness into the two protagonists’ lives; instead, many commentators deemed Antichrist confused, even misogynistic, in its representation of the two protagonists.2 This being the case, my analysis of the violent woman in Antichrist focuses on the interaction of the film’s art-horror modality with its gender representations. I consider how the film deploys horror aesthetics and tropes to frustrate the spectator’s desire for knowledge of the Woman: an epistemophilia elicited in the film’s construction of her as an hysteric.

A mutual misunderstanding

The story of Antichrist is told in several parts. In the first section, the ‘Prologue’, the Man and Woman have sex together in their urban apartment. Caught in the passion of the moment, they fail to notice as their young son, Nic, escapes from his crib, crawls up to the windowsill of his nursery and falls to his death through the high window. In the film’s first chapter – which an intertitle refers to as ‘Chapter One: Grief’ – the Woman is so disabled by heartache following Nic’s death that she is admitted to hospital, where she stays for several weeks. Once she returns home, she suffers from panic attacks, intense sexual urges and bouts of crying. The intensity of her emotion compromises her relationship with her husband who, to complicate matters further, takes charge of her psychotherapy. The chapter therefore consists of several lengthy scenes in which the pair bicker over long-harboured resentments while ostensibly engaged in therapy. Angered by her husband’s attention, the Woman declares: ‘I never interested you until now that I’m your patient.’ The Man responds by maintaining his cool professional demeanour, an act that only further irritates his wife.

In the second part – entitled ‘Chapter Two: Pain (Chaos Reigns)’ – the pair relocate to their woodlands cabin, suggestively called ‘Eden’, to undertake intensive counselling sessions. When they get there, however, a number of bizarre and supernatural events take place in the woods. Oak trees drop acorns from their branches in bizarre quantities; the woodland animals begin to speak; and human limbs emerge mysteriously from the soil. In ‘Chapter Three: Despair (Gynocide)’, the Man and Woman’s arguments intensify as therapy progresses. Referring to her scholarly research on witchcraft, misogyny and ‘gynocide’ in medieval Europe, the Woman declares that the natural world is Satanic and evil. By extension, she reasons, so, too, is womankind. Shortly after making this statement, the Woman attacks her husband. Although the Man initially attempts to flee, the Woman tearfully pursues him, bludgeons his genitals and attaches a large millstone to his leg to prevent his escape; she also castrates herself with a pair of scissors. The events reach their climax in ‘Chapter Four: The Three Beggars’. After a prolonged struggle, and believing that there is no other way to escape, the Man strangles the Woman to death in rage and despair.

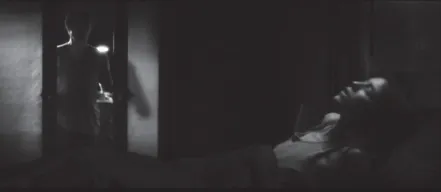

On one hand, this story of female psychological disturbance reinscribes a set of well-established – and problematic – ideas about violent femininity. As it is explained and performed in the film, the Woman’s symptomatology strongly recalls the defunct medical diagnosis of hysteria. Rather than adhering to one single proponent’s view of the malaise, however, the Woman performs a repertoire of symptoms that have, at various times, been associated with the illness in Western medical discourse. For example, her physical afflictions recall those described by Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud in their analysis of ‘Anna O.’, a patient featured in their book Studies on Hysteria; like Anna O., the Woman in Antichrist suffers from neuralgia, hallucinations and mood swings (1974: 74–81). The Woman’s performance of these symptoms is also reminiscent of Jean-Martin Charcot’s photographs of hysterics at the Sâlpetrière Hospital published in 1878–81, Iconographie photographique de la Sâlpetrière. In a scene shortly after the Woman returns home from hospital, for example, she experiences a nightmare and panic attack while lying in bed (a location where many of Charcot’s hysterics were photographed). As she arches her body, her chest rises and falls rapidly, mimicking the ‘hysterical seizure’ or ‘grande hystérie’, a full-body episode that supposedly resembles both childbirth and orgasm (Showalter 1993: 287) (Figure 1.1). During the sequence, a montage of her symptoms appears onscreen: a dilated pupil, a palpitating chest and twitching fingers. Dark and blurred at the peripheries with an ominous drone rumbling over the soundtrack, this montage not only directly presents the symptoms of the Woman’s hysteria for the viewer’s attention, but also adopts a hysterical aesthetic, simulating the ‘disturbances of vision’ and aural hallucinations that Breuer and Freud describe (1974: 74).

Precisely by referencing hysteria so strongly in the plot and mise-en-scène, however, Antichrist in fact engages in a critique of the subjectifying medical power that the Man wields over the Woman. Although the film rearticulates a ‘mad’ or ‘bad’ cultural narrative of female violence – a formulation that imagines women’s aggression as a product of either her intrinsic evil or insanity (Morrissey 2003: 33) – it is also highly concerned with problematising masculine authority. As Larry Gross suggests, ‘von Trier doesn’t have a problem with women. He has, on the other hand, a serious problem with men’ (2009: 42). Through the Woman’s fate, the film dramatises the precise point made by psychiatrist Eliot Slater in his essay on hysteria’s therapeutic deficiencies. Far from being a true medical condition, Slater writes, hysteria has always indicated an analyst’s lack of medical knowledge. ‘In the main,’ Slater writes, ‘the diagnosis of “hysteria” applies to a disorder of the doctor-patient relationship. It is evidence of non-communication, of a mutual misunderstanding’ (1982: 40). Such misunderstanding is a central theme in the plot of Antichrist. The narrative insistently focuses on the Man’s inability to comprehend his wife’s experience, an incompetence that the film expresses on a narrative level. In spite of his initial belief to the contrary, the Man is never able to determine the true cause of the Woman’s affliction. First the Woman tells him that she is afraid of the forest; hence, the Man surmises that his wife’s fear is caused by ‘nature’. Then, when the Woman declares that ‘nature is Satan’s church’, the Man revises his initial hypothesis, deciding that it is Satan, not nature, which terrifies her. Finally, the Man concludes that the Woman’s greatest fear is herself, although the Woman attacks him before he can explore the implications of this revelation. These events certainly suggest a disorder of the doctor-patient relationship. Confused and enraged, the Man strangles the Woman to death, thereby permanently eliminating the threat she poses to his life and his authority as an analyst.

Figure 1.1 The Woman experiences a panic attack; Antichrist (2009)

By so strongly emphasising the ‘disordered’ doctor-patient relationship, Antichrist uses the figure of the feminine hysteric to foreground the oppressiveness, and limits, of masculine knowledge (rather than, for example, femininity’s horror). This strategy is not unproblematic, however. In ending so violently and with few conclusions about the ‘true’ cause of the woman’s illness, Antichrist could be accused of ultimately representing the violent, hysterical woman as an unsolvable enigma – an unresolved conundrum with which to undermine masculine authority. The short ‘Epilogue’, for example, seems to construct femininity as a mysterious phenomenon. As the Man walks alone and injured through the forest at Eden, dozens of women appear suddenly from behind the grassy foothills. Their faces are blurred, leaving the Man to watch confusedly as the group marches deeper into the forest. Thus stripped of their individuality, these women seem to symbolise a supernatural or possibly even malevolent force of femininity, just as the Woman claimed. However, the image of the Man standing mystified as the women swarm around him foregrounds his ignorance. Male misunderstanding, rather than the horror of femininity, is the point that concludes Antichrist.

Horror, drama and generic provocation

Antichrist also undertakes several formal manoeuvres that position violent femininity as an expressive tool for critiquing male power. The first of these is its combination of ‘art’ cinema themes with horror-film tropes. In an article written shortly after the premiere of Antichrist at Cannes in May 2009, Larry Gross describes von Trier’s film as a confused text that poses an uncertain depiction of female subjectivity. According to Gross, this is due to the film’s inability to conform to either the tenets of dramatic realism or horror film:

Antichrist is both inspired and disabled by von Trier’s ambition to link a psychodramatic art film to a horror movie. And this boils down to the film’s evasive uncertainty about whether to represent [the female protagonist] as a case of psychological trauma or an incarnation of mythic evil. (2009: 44)

Like Gross, many other reviewers saw the film’s turn to supernatural events, and the violence that accompanied it, as having problematic implications for the film’s depiction of femininity. Mette Hjort argued that the film’s enactment, at its conclusion, of ‘extreme misogyny’ – such as the gruesome female castration and scenes of spousal violence – was not adequately justified by von Trier’s artistic ‘prerogative’ to challenge his audience (2011: n.p.). Other reviewers criticised the film’s apparent lack of a clear meaning or message. Catherine Wheatley claims that Antichrist is ‘littered with opaque symbolism’ (2009: n.p.); Scott Foundas states that it is a ‘juvenile, knee-jerk provocation’; whereas Todd McCarthy found it unsophisticated, describing Antichrist as ‘a big fat art-film fart’ (2009a: 16). Foundas and Wheatley also interpreted the generic twist as a sign that von Trier intended to ridicule his audience. Foundas declared that the director was ‘taking the piss’ and Wheatley argued that Antichrist amounted to ‘a supremely intelligent act of bad faith, directed with deliberate vitriol at the middle-class audiences whose relationship with the director and his films has always been so bitterly wrought with conflict’ (2009: n.p.). According to Wheatley’s hypothesis, Antichrist is a hoax designed to mock the pretensions of its art cinema audience.

Whether the film’s generic duality is due to directorial overreach or ‘juvenile’ provocation, the shift in narrative logic in Antichrist has implications for its representation of the Woman’s violent hysteria. As I indicated in the Introduction to this book, prevailing constructions of contemporary ‘art’ cinema encourage specific modes of appreciation; critical emphasis on characterisation and la condition humaine frequently turns the spectator’s enquiring gaze upon the human subject. Antichrist invites precisely this kind of engagement; provocatively, however, it reneges on the viewing pleasure that it promises in its early chapters. After Nic falls to his death, the Woman’s deep depression becomes a plot event that requires resolution; it is the puzzle that organises the narrative. The spectacle and narrative fact of her grief encourage spectators to scrutinise her symptoms for clues regarding the nature of her malaise and to participate in her diagnosis, casting the Woman in the role of hysteric and the onlooker as analyst. A series of intense physical spectacles in the early parts of Antichrist reinforce this positioning: the Woman suffers panic attacks, hyperventilates, and, in one scene, beats her head against the edge of a porcelain toilet bowl. The Woman – her emotions and her subjectivity – becomes the enigma that initiates the narrative and positions the viewers in a state of non-knowledge about the woman onscreen. Moreover, the dialogue in these scenes invokes the discourse of psychology as a basis for understanding her behaviour. The Man insists that the Woman’s grief is ‘not a disease’ but ‘a natural, healthy reaction’ and encourages her to explore her emotions. The Man is clearly overconfident in his approach; he superciliously brandishes his wife’s medication and insists that she return home from hospital. Yet his words signal that the Woman’s malady can be made intelligible according to the principles of psychological motivation and causality. In keeping with David Bordwell’s description of the art-film text, Antichrist is initially established as a film interested in the human condition, a film ‘of psychological effects in search of their causes’ (1979: 58). The exposition thus suggests that Antichrist will provide some resolution to the Woman’s affect. It creates the desire for insight about her overwhelming grief and, at the same time, about her fraught relationship with her husband.

The film’s conclusion spectacularly disappoints these expectations. Rather than maintaining a characterisation of the Woman’s violence as having its aetiology solely in psychological distress, the plot events of Antichrist pose a second possibility: that her behaviour is attributable to her inherent and supernatural feminine evil. The mysterious events that occur midway through Antichrist enact a generic shift away from psychological realism towards a regime of verisimilitude more appropriate to horror cinema. Once the Man and Woman arrive at their cabin in woods, for example, ominous events begin t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Horror, Hysteria and Female Malaise: Antichrist

- 2. Science, Sensation and the Female Monster: Trouble Every Day

- 3. Sex and Self-Expression: Fatal Women in Baise-moi

- 4. Romance and the Lesbian Couple: Heavenly Creatures

- 5. Film Biography and the Female Killer: Monster

- 6. Evincing the Interior: Violent Femininity in The Reader

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Selected Filmography

- Index