eBook - ePub

The Millennial Generation and National Defense

Attitudes of Future Military and Civilian Leaders

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Millennial Generation and National Defense

Attitudes of Future Military and Civilian Leaders

About this book

This study captures the attitudes and values of the youth generation of college students in the USA toward the military, war, national defence, and foreign policy matters. Providing a unique insight into civilian and military Millenials, the authors explore the impact of 9/11 and the level of tolerance within the military.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Millennial Generation and National Defense by Morten G. Ender,David E. Rohall,Michael D. Matthews in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Millennials on the Rise?

Abstract: Who are the Millennials? This chapter provides a review of the literature on this cohort born in the late 1970s up through 2000. Their characteristics are described and the significant events that have shaped the Millennial generation are highlighted with an eye toward connections to national defense. Second, the chapter provides a description of the backgrounds and histories of military academies and the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) system in the United States. Next, the three eras of civil-military relations in the United States dating back to the end of World War II are discussed and the authors put forth that American society has entered a new, fourth phase of civil-military relations. Finally, the chapter is rounded out with an introduction to the BASS study sample.

Keywords: attitudes; civil-military relations; generations; military academy; Millennials; ROTC

Ender, Morten G., David E. Rohall, and Michael D. Matthews. The Millennial Generation and National Defense: Attitudes of Future Military and Civilian Leaders. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137392329.

I am most concerned. I am entering the Army soon. Why do some civilian people have so much hatred of the military and not a lot of respect? We are the people risking our lives for the freedoms they enjoy each day.

20-year-old, female, bi-ethnic, ROTC cadet, and Marketing major

The aim of this book is to examine a generation of youth and their attitudes toward the role of the military in American society and other issues of national defense. We deliver a batch of numbers in this book. The numbers require us to bring together strands of social research ranging from the study of the Millennials generation and who they are to the study of the military-civilian gap hypothesis, essentially that there is an ongoing expansion and contraction of fissures in the cultures that exist between the types of people who serve in the military and the larger civilian society in which it is embedded. In this chapter we first discuss who the Millennials are and compare them to peer cohorts of previous generations. Next, we highlight characteristics of Millennials. We then turn to the post-9/11 military. Specifically, the Millennials and the military and civilian-military relations in the period after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York City, Washington, DC, and Pennsylvania. We conclude the chapter with a description of the BASS data as the major sources of information for the findings discussed in the remaining chapters of the book.

The US relies on cohorts of Millennials to self-select into the military for America’s defense future (Drago 2006). They will comprise the organization and carry out the orders handed down by the civilian and military leadership. But this generation is often portrayed as both selfish and weak. Can this generation meet the challenge of defending the country? The short answer is “yes.” That is, they are already doing it and given their performance in Iraq and Afghanistan, it is clear that they are up to the task. The issue is about the future: will there be enough of them willing to serve and lead? Can we rely upon them to continue joining the American armed forces in sufficient numbers to maintain a large enough force to meet the missions of the future? Once in, will they remain in the ranks long enough to maintain the leadership structure? Of great interest, what are their views on national defense and related matters? What is their opinion regarding the structure of the military? What are their attitudes toward the role of the military in the democracy and a global world? What about those who do not volunteer, how do they view the military? Who should serve when not everyone does? And, finally, how and in what capacity should people serve?

Who are the Millennials?

Before answering who are the Millennials, it is necessary to answer the bigger question: what is a generation? In sociology and demography, the fields that define and study generations, a birth cohort refers to a group of people born within the same time period. People sometimes use the word “generation” to refer to a birth cohort. Popular discussions of the influence of birth cohorts have focused mostly on the influence of the Baby Boomer generation. Boomers are people conceived after the end of WWII and born beginning in 1946. Their reign as a birth cohort ends somewhere between 1960 and 1964 (Howe and Strauss 1992). The Boomer Generation is one of the largest birth cohorts in American history. Hence a baby boom that began with the return of millions of American service members back into the US after WWII. They quickly married and started families as they concomitantly prospered in an economic boom that followed in the 1950s.

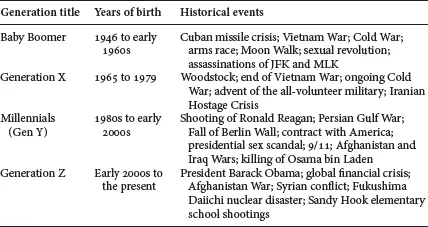

The Baby Boomers experienced some of the greatest cultural and technological changes in American society: the space race, Woodstock, and the sexual revolution, for example. They also witnessed momentous national tragedies such as the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The generations, years, and historical events listed in Table 1.1 highlight some of the watershed moments for Boomers and the three subsequent generations. Notable Boomers are George W. Bush (born July 6, 1946), Oprah Winfrey (January 29, 1954), and Barack H. Obama (August 4, 1961). Early Boomers came of age during the Vietnam War. The earliest came of age in 1968, the year of the Tet Offensive, a major battle in Vietnam involving the Americans and North Vietnamese forces and considered the tipping point in the war resulting in the eventual American withdrawal. Younger Boomers came of age at the time of the Iranian Hostage Crisis, when Iranians overtook the American embassy in Tehran, Iran and held 52 Americans hostage. They were held captive for 444 days and released immediately after President Ronald Reagan took office in January 1980.

TABLE 1.1 Generations, years, and significant historical events

The “Greatest Generation” moniker (popularized and somewhat romanticized by Tom Brokaw, the former NBC News anchor, in 1998) refers to a cohort of Americans who fought in WWII (and those who maintained the home front). Social researchers, however, refer to this group as the “G.I. Generation.” They are a cohort born between 1901 and 1924 (Howe and Strauss 1992). Many of these people became the parents of the Baby Boomer generation.1 Their grandchildren are of another generational cohort, Generation X.

The generation following the Baby Boomer generation became popularly known as Generation X, Gen X or Xers, for shorthand. The next generation, the one we and most social researchers refer to as Millennials, has at times been called Generation Y or Gen Y. In fact, to stay with the letter trend, so far, one journalist has referred to the generation born after the Millennials (2000s to present) as Generation Z (Horovitz 2012). Millennials have also been referred to as Generation Me; Echo Boomers; Baby Boom Echoers; Generation Next; and Nexters. There are even popular subgroup labels within different generations such as the Beat Generation among Boomers and the MTV Generation among Xers. Regardless of the label, it is less than precise to pinpoint the year when one generation ends and another one begins but the US Census Bureau formally uses Baby Boomers to describe the group born between 1946 and 1964. Hence, we can safely say that Gen X (sometimes called the Hip Hop Generation) begin to be born sometime after the early to mid-1960s. One notable book, Millennials Rising, defines Millennials as those people born after 1982 (Howe and Strauss 2000). Alternatively, Pamela Paul (2001) defines them as being born between 1977 and 1994. Jean Twenge (2006) combines some of the Gen X group with the Gen Y by using birth dates between the 1970s through the 1990s. Therefore, there is no definitive year upon which to define Millennials in the literature. We will rely on 1982 as a compromise date. It is the average year among the researchers and places it as the beginning birth date for Millennials. This places the first cohort emerging as adult Millennials and most importantly, the legal eligible age for military service, around 2000, the beginning of the new millennium.

Research shows that when we are born can impact our personality and our life in general. Research that scientifically links the effects of large-scale historical forces on our personal lives is called life course sociology (Elder 1994). Several studies show that people from different generational cohorts appear to experience varied social psychological outcomes. John Mirowsky and Catherine Ross (2007) found that the positive effect of education on one’s sense of mastery (sense of control over one’s life) is greatest among younger cohorts: education has a stronger effect on younger people today than it did for the same-aged group in previous generations. They argue that this finding is a result of the increased need for mastery among younger cohorts to help them manage more complex economic and technological conditions in a postindustrial world. Another study found African Americans born before the classic and groundbreaking Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education (before 1957) to be socialized about race differently than younger cohorts (Brown and Brown 2006). According to the authors of this study, youths born in older cohorts received more messages conveying deference to and fear of whites than African Americans born during or after the race protests of the mid-1900s. The study also showed that current racial attitudes are linked with socialization experiences one has as a child.

Life course sociology provides a key in this book because it helps to think about the parameters for studying generations.2 First, according to life course sociology, not all historical events impact all people in a culture. In his classic study of the effects of the Great Depression, Glen Elder (1999, originally 1974) found that most of the effects of this momentous and emotional social event were felt only among children who had firsthand experience with economic hardship. Children who lived in families that lost no income did not change as result of the Depression. The implications of such a finding are that some collectives of people experience major social events more acutely. Others might move along relatively untouched by public events. Today, while some people are immensely touched by one event, say the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii by the Japanese and marking the US entry into WWII (Tuttle 1993) or the 9/11 terrorist attacks setting the stage for invading Afghanistan and later Iraq (Ender, Rohall, and Matthews 2009b), others are concomitantly less fazed by an event in any significant way. Certainly being away from military experiences during these events fazes one less than those with military experience (Ender, Rohall, and Matthews 2009a).

How do we get affected by one historical or cultural event and not others? According to life course sociology, it depends on several factors. First, it depends on our exposure to those events: did we actually experience the event or its effects directly? People who experienced Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and coastal Mississippi in 2005 were more hurt by it than people who simply watched it on television. In addition, we can be affected by such events via linked lives, knowing someone who is going through a divorce is likely to impact us more than if we simply hear about it through someone else. It is also crucial to remember that people have what social scientists call agency, the ability to think and act independently of social environments. Even events that should impact us directly may not. We may simply make decisions to not let them “get to us.” Psychologists refer to such adaptive measures as drawing on resilience or possessing grit (Matthews 2014).

We know that people change. Groups of people growing up during the same time period are somewhat different from their parents and their children. What it means to be a man or woman, an adult or child, a particular race or ethnicity, is partly driven by history and scholars confirm this (Danigelis, Hardy, and Cutler 2007; Davis 2006; Gilleard and Higgs 2005; Johnson, Berg, and Sirotzki 2007; Percheski 2008). Such studies relate to one of the most basic principles of sociology: that social reality is constantly changing over time based on changing social interactions and social structures. However, it also reflects another principle of social psychology: that our social identities, our positions in society, also impact how we react to life events. High-status individuals have more social capital (education, money, and so on) with which to manage a personal crisis when it arises. But they are also more involved in societal events, tracking news more closely. They anticipate public problems and can adjust. Sociologists refer to this as possessing sociological imagination. It is the ability to connect public issues to one’s personal life (Mills 1959). In context of the life course, our social position (for example, race and class) can influence our reaction to historical events (Doyle and Kao 2007; Johnson, Berg, and Sirotzki 2007). People most affected by historical times are likely those people directly and actively involved in them.

What are some of the historical events that are said to impact Millennials’ personality? Pamela Paul’s book, Getting inside Gen Y (2001) examines the 71 million Americans born between 1977 and 1994 (age 15 to 32) when the analysis first appeared in 2001. This group is almost as large as the Baby Boomer generation (1946–64), the post-WWII generation (78 million). Paul interviewed sociologists, demographers, and market researchers to get their take on Gen Y. Did history and culture create a new way of doing things? What historical themes mattered most? Some of the critical factors shaping Gen Y, according to Paul’s research, include MTV, O. J. Simpson, President Clinton, and the Columbine High School massacre. MTV’s The Real World in 1992 ushered in an era in which visual style trumped content. Celebrity scandals such as the O. J. Simpson murder trial from 1994 to 1995 and President Clinton’s possible impeachment from a sex scandal in 1998 led many of this generation to value privacy while dropping the unquestionable admiration of public leaders. The Columbine High School massacre in 1999 caused American kids and their parents to be more wary of safety and mistrustful of the media.3 Baby Boomer and Gen X parents of Gen Y/Millennials became known as “lawnmower” and “helicopter” parents. They adopt a parenting style that metaphorically first grooms the life paths of their children and then hovers above their life-world. Such parents are hyper-parental, overly cautious, and are excessively involved in their children’s lives. The research literature also identified an increasing amount of both racial and cultural diversity in this generation, suggesting they are one of the most tolerant generations in American history. Finally, Paul argues that with the growing numbers of talk shows and reality television, many youths began to believe that they too can become star celebrities; that they are of great consequence, worthy of national, even international attention.

Jean Twenge (2006) extends Paul’s work by looking at survey data examining “Generation Me.” Noted above, Gen Me combines some of the Gen X group with the Millennials. Twenge (2006) finds that this generation is much more individualist than past generations. It is cautionary to note that we are not talking about comparing older and younger people. We know from sociological research that people change their values and beliefs as they age and take on new roles and experiences. Typically this means that people tend to become more conservative as they age. But Twenge points out that younger people today are more individu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Millennials on the Rise?

- 2 Millennials Attitudes toward Military Service

- 3 Millennials Attitudes on the US Armed Forces

- 4 Millennials and Wars: Iraq and Afghanistan

- 5 Millennials and Diversity in the Armed Forces

- Conclusion

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index