eBook - ePub

Immigration and Citizenship in an Enlarged European Union

The Political Dynamics of Intra-EU Mobility

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Immigration and Citizenship in an Enlarged European Union

The Political Dynamics of Intra-EU Mobility

About this book

A distinctive contribution to the politics of citizenship and immigration in an expanding European Union, this book explains how and why differences arise in responses to immigration by examining local, national and transnational dimensions of public debates on Romanian migrants and the Roma minority in Italy and Spain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Immigration and Citizenship in an Enlarged European Union by Simon McMahon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: The Politics of Immigration and Citizenship in an Enlarging European Union

In October 2007, the body of Giovanna Reggiani was found in a ditch in a northern suburb of the city of Rome, Italy. The police, politicians and press immediately initiated a hunt for her killer, who would be revealed as the Romanian Romulus Nicolae Mailat. Perceptions of Romanian immigrants as a violent, criminal threat to Italy burst out in spectacular fashion. Walter Veltroni, the Mayor of Rome from the centre-left Democratic Party (Partito Democratico, PD), declared that the accession of Romania to the European Union (EU) earlier that year had opened the doors to the arrival of particularly aggressive criminals, and that there were ‘too many Romanians [ ... ] who do inacceptable things’ (Il Sole 24 Ore, L’opposizione contro Governo e Veltroni: interventi tardive, 1 November 2007, Barbagli 2008). Romanians in Italy were defined as ‘crime-tourists’ (Il Giornale, I turisti del crimine, 4 November 2007), and the areas of their settlement as dangerous places ‘where women are killed and raped in front of everybody’ (Il Sole 24 Ore, L’opposizione contro Governo e Veltroni: interventi tardive, 1 November 2007). Mass deportations were suggested as the answer, with the Rome Prefecture rapidly announcing that 5,000 Romanians could be expelled in order to ‘clean the water of infected fish’ (La Repubblica, Romeni, scattano le espulsioni. “Via i primi cinquemila”, 2 November 2007). When the Romanian government suggested that the treatment being directed at this population was disproportionate, the response from the right wing MP Paolo Grimoldi was to ask why they had not shown ‘the same concern when their citizens invaded our cities, stole from our aged citizens and raped our women?’ (Movimento Giovani Padani, La Romania non ci faccia ramanzine e si riprenda i suoi delinquenti, 6 November 2007). Across the political spectrum, from those in power to those in opposition, the consensus dictated that Italian citizens were the victims of a dangerous, criminal Romanian immigrant population. Romanians were unwanted.

In the Spanish town of Badalona, on the outskirts of Barcelona, tensions also arose in 2010 when electoral pamphlets were published stating ‘we do not want Romanians’. The pamphleteer, the conservative candidate Xavier García Albiol, argued that a group of Romanian gypsies had committed too many crimes and lowered the security of the area. Yet, the pamphlet was met with a barrage of criticism; Albiol’s party disassociated itself from him, and the president of the regional wing of the party publicly apologised for causing any offence. A manifesto from 74 trade unions, NGOs, charities and immigrant associations warned of ‘the increase of racism and xenophobia in Catalan politics’, and the right wing politician Felip Puig stated that ‘the discourse of Mr Albiol brings together all that I fully reject and that Convergence and Union [his party formation] wants to eject from political debate’ (CDC Noticies, Felip Puig reclama al PP no utilitzar la immigració com a moneda de canvi partidista, 12 November 2010). In April 2010, a case was presented against Albiol under Spanish penal law on offensive material (Organic Law 10/1995, Art. 510) and racial discrimination (art. 607bis), brought by a group of organisations led by the human rights organisation SOS Racismo (El Pais, El PP juega con la xenophobia, 27 April 2010). These responses reflect how in Badalona and across Spain, there was wide consensus on Romanian immigrants being considered at risk of being unfairly stigmatised.

These two examples are illustrative of a more general distinction in responses to the presence of Romanian immigrants in Italy and Spain: in the former, this nationality has been negatively represented, and there has been an escalation of inflammatory rhetoric, while in the latter, such a critical, aggressive approach has not been common, and in fact quite the opposite has been found. This raises two sets of significant questions, which will be the focus of this book.

Firstly, following the accession of Romania to the EU in 2007, the immigrants referred to in such different ways in Italy and Spain have enjoyed the same status of citizens of the EU in both countries. What has been the impact of this changing status on the status of Romanian immigrants? Why does this impact vary from one place to another?

Secondly, as is evident, tension, discrimination, exclusion or stigmatisation may or may not arise with the presence of immigrants. But why do distinct responses arise in different places? And what, in the specific cases of Italy and Spain, has brought about such distinct responses to Romanian immigration in particular?

However, these questions should also be understood in the light of two further sets of secondary questions. The first is that from 2007 onward, the countries examined here have been subject to dramatic situations of economic decline and uncertainty, with rising unemployment rates and declining wealth for many. They therefore provide an important opportunity to examine the impact of a period of economic crisis on the politicisation of immigration, asking whether economic conditions and the politics of immigration and citizenship are connected. The second examines the way that public debate on Romanian immigration in Italy and Spain has been the source of concerns regarding the ethnic Roma populations. Indeed, Romanian nationality and Roma ethnicity have often been conflated and assumed to be equal and the same, with significant implications for the way that political debate about them is shaped. The study of the politics of Romanian immigration in the recent period thus provides a vital lens through which to examine some of the most salient political issues of contemporary Europe: the relationship between crisis and politicisation of immigration, and the living conditions and status of the Roma.

Addressing these questions, the primary objective of this book is twofold: to understand how and why responses to Romanian immigration have been so divergent in these countries and to explore what it means to become a citizen of an enlarging EU. It examines the way that the public debate and policy on immigration and free movement are driven above all by local, national and transnational political claims making: the boundaries of citizenship are thus negotiated and contested among political and social actors, which are in turn set in and react to specific contexts. Viewed in this way, the politics of immigration often tell us more about political dynamics in the host country than about the immigrants themselves. Indeed, it is shown here that the different responses to Romanian immigration in the political debates in Italy and Spain are due not to the cultural characteristics of Italians, Spaniards or Romanians themselves, they have little to do with ‘real’ cultural similarities or differences between hosts and foreigners, but a great deal to do with the relations of power concerning who can influence and control this process and who cannot. In doing so, this book stands against the prevalent idea in much academia and politics that the presence of immigrants is problematic due to the way that they constitute a culturally diverse and problematic group of outsiders among host society citizens (see, for example, Huntington, 1996, 2004; Kymlicka and Norman, 1994, 2000; Putnam, 2007; Schlesinger, 1992; Walzer, 1983; Wiener, 1995).

Furthermore, by examining how claims making dynamics have influenced the debate on Romanian immigration prior to and immediately after this country’s accession to the EU in 2007, this book also enables us to trace the shifting status of intra-EU migrants in different localities. The contemporary significance of an understanding of these topics is unquestionable in a European context in which international migration has become a fiercely contested political issue, where millions of mobile workers and third country nationals now reside in countries extraneous to their place of birth, and economic crisis continues to afflict countries particularly in Southern Europe. Indeed, Romanians represent the second largest single nationality population of migrants in the EU, totalling over 2.5 million registered individuals (data from Eurostat). The study contributes to an understanding of European political integration and citizenship in the EU by examining what it means for a population of geographical, political and legal ‘outsiders’ of the EU project, as the Romanians were until their country’s accession to formally become citizens ‘inside’ the EU. Much academic literature has expected this supranational citizenship category to cause a shift in individuals’ status to one of equality of rights, loyalty towards shared institutions and a sense of united cultural and political belonging (Eder, 2006; Herrmann and Brewer, 2004; Laffan, 2004; Maas, 2007; Spohn, 2005). However, throughout this book it will be argued that the legal category of EU citizen provides only an opportunity for such a development, the impact of which is dependent on local, national and transnational dynamics of political mobilisation and claims making. The legal category of EU citizenship provides an opportunity for change, but the way in which this occurs is variable across locations.

Why Italy and Spain?

The argument that will be developed in this book states that the politics of immigration cannot simply be explained by looking at the migration experience in Italy and Spain or the nature of the immigrant populations in these countries, but must examine the political contestation that determines how the presence of immigrants is given meaning in debate and policy. Indeed, Italian and Spanish experiences of immigration, and the main case study of the Romanian populations in these countries, are broadly similar.

A wide range of academic research has already suggested that Italy and Spain are comparable in their experiences of immigration, including them within a general ‘Southern European’ model of immigration (for example, Arango et al., 2009; Baldwin-Edwards, 2001; Calavita, 1998, 2005; Castles and Miller, 2003: 82–85; King, 2001; Triandafyllidou, 2009; Schierup et al., 2008: 102–107). Migration flows to the Southern European countries have been described as contrasting the post-war labour migration experience of Northern European ones, which was largely state-regulated (but not entirely, see Huysmans, 2000) and drew migrants from a limited range of geographical origins and was seen as temporary, with return assumed (at least in theory) once their labour was no longer necessary (King and Thomson, 2008: 267). In the Southern European countries, the rapid growth and diversity of migratory flows has been seen as a ‘surprise element’ for policymakers who were not expecting immigration at all (King et al., 1997: 4). In response to insufficient ad hoc, piecemeal and often ambiguous policy approaches to immigration and integration, the key structures for the incorporation of foreigners in these countries have been the labour market and interpersonal networks rather than host society political or social institutions (Triandafyllidou, 2009: 51). Legal residence has been tied to employment, which has itself been shaped by a demand for cheap and flexible precarious workers in secondary and informal or underground labour markets, resulting in a large degree of immigrant residence in Southern Europe being undocumented (King, 2001: 18). The outcome has been a context in which immigrants enjoy little access to rights or representation, as well as the seemingly paradoxical situation of rising immigration rates at a time of rising unemployment (Mendoza, 1997).

Both Italy and Spain have considerable histories of emigration and immigration. Just to consider, from centuries of movement around the Mediterranean to the arrival of tourists and retirees from Northern Europe and workers from North Africa in the twentieth century, foreigners have been moving to both countries before they became net receivers of immigration (Carfagna, 2002; King, 2001). However, since the 1980s, a quantitative shift in the size of migratory flows to these countries has made them two of the principal receivers of immigration to the EU while a qualitative diversification of countries of origin has brought migrants from new places such as Albania (Italy), Latin America (Spain) and Romania (Italy and Spain). Indeed, data from Eurostat signals that in 1988, only 85,791 registered immigrants arrived in Italy and 24,380 in Spain, and that this rate saw little change until the mid-1990s when it began to expand rapidly, reaching 556,714 annual arrivals in Italy and 958,266 in Spain in 2007. This produced an increase over the decade between 1998 and 2008 of the total registered immigrant population of Italy from 991,678 to 3,432,651 (according to data from Institute of Multi-Ethnic Studies, ISMU and the Institute for Statistics, ISTAT), and of Spain from 719,647 to 4,473,499 (according to data from the National Statistics Institute, INE). At the same time, continued emigration has resulted in there being 3,649,377 Italians registered outside of Italy (on the AIRE register) and 1,194,350 Spaniards registered on the Spanish census for voters resident abroad (on the CERA register) in 2007.

In keeping with the Southern European model, in both countries, underground labour markets have provided employment opportunities for immigrants regardless of their legal status, and these have been characterised by a high degree of informality and lack of regulation or social welfare provisions (Arango et al., 2009; Baldwin-Edwards, 2001; Calavita, 1998, 2005; King, 2001; King and Thomson, 2008; Hartman, 2008; Schierup et al., 2008). Immigrants thus respond to a demand for cheap and flexible precarious workers (King, 2001: 18), illustrating, as noted by Reyneri, that ‘immigrants, while they certainly do not bring the underground economy into existence, contribute to its reproduction’ (2004: 88). In response to this informality and an associated high level of undocumented residence, amnesties for undocumented migrants have been regular in both countries, coming in 1986, 1990, 1995, 1998, 2002 and 2009 (for domestic carers and nurses only) in Italy and in 1986, 1991, 1995 and 2001 in Spain. Amnesties do not result in permanent legal residence, however, because the renewal of permits is dependent on presenting a work contract. In this way, the boundaries between legality and informality in Italy and Spain are blurred and shifting.

Finally, despite the fact that Italy and Spain became countries of net immigration in the 1970s and 1980s, their first comprehensive immigration laws were only passed in 1998 and 2000, respectively. Policy objectives in both countries have been described as ambiguous and contradictory, as well as criticised for producing immigrant illegality. While Italian policies from the 1990s and 2000s have been accused of rejecting legal entry in favour of undocumented entry followed by regularisation amnesties (Colombo and Sciortino, 2004b: 66; see also Sciortino, 1999; Reyneri, 2004; Zincone, 1998, 2006), Spanish ones have been criticised for tying relatively short residence permits to precarious work contracts, thereby actively ‘irregularising’ immigrants by making it all but impossible to retain legal status over time (Calavita, 1998: 531; see also Cachón Rodríguez, 2009; Calavita, 1998; Schierup et al., 2008). In this context, immigrants have had few formal opportunities for stable residence, enfranchisement or sustained political participation in either country.

The political, economic and social circumstances of Romanian immigration to Italy and Spain mirror these general patterns. Migration flows began arriving in the 1990s but grew very quickly. Under the Romanian Communist Party regime, restrictive control policies for most residents prohibited emigration without Securitate secret surveillance, until the regime’s fall in 1989 (Sandu et al., 2004: 3; Stan and Turcescu, 2005). During the early 1990s, emigration was primarily directed to Germany, with small flows to Italy as rising unemployment in Romania was accompanied by falling GDP and rising inflation from 1.9% to 210% in 1992 (according to the Institutul National de Statistica Romania, see also Ban, 2009; Maddison, 2008; Sandu et al., 2004). The decline in living standards acted as a push factor for emigration while comparatively high salaries in Europe acted as a pull factor, encouraging movement in search of employment and stability (Ban, 2009; Sandu et al., 2004). Indeed, despite fluctuations throughout the decade, by the year 2000, the average monthly salary of a Romanian citizen was equivalent to 150 euros, compared to over 1,900 in the Eurozone (Viruela Martínez, 2002: 234). The emigrants at this time were mostly educated individuals leaving Romania to look for professions that would enable them to earn a wage more fitting to their qualifications, bridging the education-income gap of their homeland (Uccellini, 2010; Viruela Martínez, 2002).

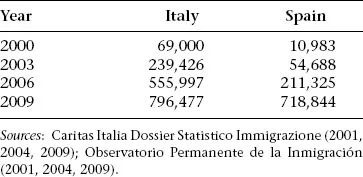

These migratory patterns changed in 2002, when a combination of lowered legal constraints on entry to EU Member States and improved travel connections contributed to flows growing and becoming more dynamic, with settlements often more temporary (Sandu et al., 2004; Viruela Martínez, 2008). Visa requirements for entry to the EU for stays of up to three months were removed, simplifying entry. In addition, increasingly stable cross-border Romanian migration networks helped people move to destinations such as Italy and Spain where friend and kinship networks helped them find labour market opportunities (both regulated and informal), housing and so on (Cingolani, 2007; Cingolani and Piperno, 2005; Elrick and Ciobanu, 2009; Eve, 2008; Gabriel Anghel, 2008; Hartman, 2008; Marcu, 2009, 2011; Pajares, 2007; Potot, 2008; Sandu, 2005; Viruela Martínez, 2002, 2008). This ease of travel was confirmed in 2007 by the accession of Romania to the EU, granting nationals from these countries rights to freedom of movement between Member States, although not without restrictions, as will be discussed in the following chapters. These changes in migration patterns meant that, despite forming a very small population in Italy and Spain in 2000, by 2009, Romanians were the highest ranking in size in immigration in both of these countries (see Table 1.1).

The growth of the Romanian population in Italy and Spain prior to and soon after the accession of Romania to the EU in 2007 was therefore constant and rapid, while also undergoing a change in composition as migrants have arrived not only from Romania’s urban middle classes, but also the rural poor, and chosen to live all across Italy and Spain, from small villages to the large cities (Sandu, 2005). Despite these diverse backgrounds, the dominant employment roles in Italy and Spain have been restricted to domestic care, construction and agriculture (Birsan and Cucuruzan, 2007; Caritas Italia, 2010; Hartman, 2008; Marcu, 2009; Perrotta, 2006; Viruela Martínez, 2008). Informal employment in these sectors has meant that legal residence and work permits have not been absolutely necessary in order to enter the labour market while waiting for a regularisation amnesty or to save money to return to Romania (Gabriel Anghel, 2008; Perrotta, 2006; Uccellini, 2010). In both countries, precarious or informal employment and undocumented residence, among other factors, have nevertheless given Romanians little stability, few opportunities for political representation and restricted bargaining power with their bosses or within trade unions (Perrotta, 2006). However, the granting of a new EU citizenship status to two comparable populations such as these in 2007 provides a particularly interesting opportunity to see how a supranational structural–legal change can influence the local and national political integration of immigrants in Europe.

Table 1.1 Growth of Romanian immigration to Italy and Spain post-2000

The politics of immigration in research

It has been widely noted in much research that the presence of immigrants can become an increasingly contentious and controversial source of tension, conflict and discrimination (see, for example, Ariely, 2012; Buonfino, 2004; Bu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction: The Politics of Immigration and Citizenship in an Enlarging European Union

- 2 Defining Who Is Who in the Politics of Immigration

- 3 The Structural Context of Immigration to Italy and Spain

- 4 The National Politics of Immigration in Italy and Spain

- 5 The Local Politics of Immigration in Rome and Madrid

- 6 Intra-EU Migrant Politics in Italy and Spain

- 7 The Politics of the Roma in Italy and Spain

- 8 Conclusions: Becoming Citizens of an Expanding European Union

- Appendices

- Notes

- References

- Index