eBook - ePub

Commemorating Writers in Nineteenth-Century Europe

Nation-Building and Centenary Fever

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Commemorating Writers in Nineteenth-Century Europe

Nation-Building and Centenary Fever

About this book

This volume offers detailed accounts of the cults of individual writers and a comparative perspective on the spread of centenary fever across Europe. It offers a fascinating insight into the interaction between literature and cultural memory, and the entanglement between local, national and European identities at the highpoint of nation-building.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Commemorating Writers in Nineteenth-Century Europe by J. Leerssen, A. Rigney, J. Leerssen,A. Rigney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Schiller 1859

Literary Historicism and Readership Mobilization

Joep Leerssen

Crucibles of inspiration, cycles of commemoration

In 1860, Hans Christian Andersen wrote a short tale entitled ‘The Old Church Bell’. It opens by relating how an old church bell rang while a woman was giving birth, easing her labour with its festive peals. The life story of the boy is followed, and likewise that of the bell. The two lifelines reconnect when the old church bell, decommissioned and neglected, is melted down to provide the bronze for a statue; that statue is being made in honour of the boy, who turns out to have been none other than Friedrich Schiller.

The story (given in full in the Appendix below; see also Detering 2012) is vintage Andersen, irritating in its twee sentimentalism, admirable in its narrative deftness. Thematically, it plays heavily on the intertext of what was then (and still is now) a classic evergreen in the Schiller oeuvre: Das Lied von der Glocke (‘The Bell’s Song’). That 1799 ballad weaves, as Andersen’s spin-off tale was to do 60 years later, a double storyline. The stages of casting and hoisting a church bell are described in episodes which are dovetailed, in interesting back-and-forth shifts, with the successive stages in a life cycle that this bell will mark by its peals: birth, first love, marriage, parenthood, death and burial.

Schiller’s ballad itself shows some of the clever sentimentalism that Andersen took to unprecedented heights; but it is also a majestic exercise in the Romantic negotiation of the material vs. the ideal, the elemental vs. the transcendent. Ore and metal are taken from the earth, melted down in a fiery crucible, and cast into a clay form; they will emerge as a shining jewel, hoisted high into a church spire, and there, as a celestial companion to the forces of thunder and lightning, give forth disembodied sounds sanctifying the key events of human existence. Schiller’s tale of transcendence, from ore to music, is thus taken up into a new cycle by Andersen: the clapped-out bell is taken down to earth again, and thence its dumb substance is propelled afresh into a rebirth, a re-casting, a transfiguration.

Andersen quite literally recycles Das Lied von der Glocke. The bell is recycled and recast into a statue, and becomes Schiller himself; similarly the tale ‘The Old Church Bell’ recasts Schiller’s poem, melting it down and refiguring it into a different, albeit familiar shape. The theme was inspired by a specific occasion: Andersen’s visit to Stuttgart around the time of the Schiller centenary of 1859. In Stuttgart he had admired the Schiller statue made by his fellow countryman, the great Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1777–1840). In the story, Thorvaldsen plays the creative, almost demiurgic role that the bell-founder had played in Schiller’s ballad. Thorvaldsen’s Schiller statue (the first public monument to a man of letters in Germany) had been put up in 1839, after a ten-year preparation (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Schiller memorial (1839), Schillerplatz, Stuttgart. Photograph by Christoph Hoffmann.

Schiller as a figure of commemoration

The Schiller statue of 1839 and his centenary of 1859 have an almost paradigmatic status in German, and indeed in European, commemoration culture. The 1859 festivities in Stuttgart and elsewhere were widely noted, provided an inspiring example for other countries (such as Italy and the Netherlands; see Chapters 5 and 9 below), and became a prototype for the rituals and protocol of such events. The Schiller commemoration sets the tone for (or was, at least, an early, influential representative of) the type of pomp and circumstance that contemporary taste thought appropriate for such occasions; it revolves around a combination of spectacle, ceremony, collective festivity, and material statue-building. Moreover, it is prototypical in that, carried by municipal sociability and city-anchored civic pride, it catches at the same time the rising tide of nation-building fervour. And, perhaps most importantly, it shows, precisely in these decades from the 1830s onwards, a tendency to ‘reticulate’; by which I mean that various municipalities adopt the inspiring pattern and replicate it locally, themselves inspiring other cities again so that they, too, can pick up the idea. The result of this cascading process (which always involves a specific city location and therefore cannot be properly called one of ‘diffusion’) is that the landscape becomes dotted with a mnemonic archipelago, a quasi-Hanseatic League of commemorating cities increasing in expanse and density. That process of reticulation occurred within the German cultural-mnemonic community (both in the German lands proper and among exiles and emigrants) and, in a wider sense, across Europe: these patterns are picked up outside Germany by other mnemonic communities for the commemorations of their own cultural hero-figures and ‘cultural saints’ (as Dović calls them in Chapter 12).

There can be no doubt that Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805) was such a ‘cultural saint’. Together with Goethe (whose aloof irony, as well as his long-lasting and large-looming presence, caused him to be admired rather than cherished as a giant of German letters), Schiller had ignited the explosive awakening of German literature in the 1790s. His flamboyant life, good looks, and early death, no less than his titanic literary achievements in various genres, had made him the ideal of the Romantic genius. And his liberal ambitions for a freely flourishing German culture had made him the projecting screen for all unfulfilled progressive desires after 1805 (the year of his death and of the Battle of Austerlitz). As I shall argue at greater length later on, the specific importance of Schiller commemorations within Germany (for the description of which I rely on the detailed accounts of Oellers 1970 and Noltenius 1984) was that they were to a large extent the cultural, coded disguise of suppressed social and political ideals, and should be understood alongside a subversive, often repressed tradition of liberal-bourgeois ‘political feasts’ (Düding, Friedemann, and Münch 1988).

The erection of a Schiller statue had been planned by the citizens of Stuttgart since 1825, when they began to hold festive gatherings to commemorate the poet. The driving force behind these events and behind the statue was the Stuttgart choral society (men’s choirs being an extremely important social phenomenon throughout Germany in the period 1820–70; see Elben 1887, Klenke 1998). When at last the statue was unveiled, the occasion was marked by a gathering of no fewer than 44 choirs, who joined together in singing a festive cantata composed for the occasion on lyrics by the poet Eduard Mörike. In a gesture redolent of religious liturgy, the statue was then inaugurated and blessed by the classics professor Gustav Schwab, who was also an ordained minister and who predicted that it would become a place of pilgrimage. In the evening, it was illuminated by Bengal fire. By the time of Andersen’s visit it had indeed become such a place of pilgrimage; and Andersen’s reconfiguration of the church bell into a public statue aptly captures the extensive overlap at work here between the civic and the sacred.

The 1859 Schiller centenary became a galvanizing event throughout Germany and may in some measure count as the benchmark for the commemorations of writers in 19th-century Europe. It was celebrated in at least 93 German cities and in 22 cities outside Germany (sponsored by German emigrants, especially in the USA). Schiller statues began to proliferate: between 1859 and 1914, 14 of them were put up in Germany and 11 in American cities with German immigrant communities. Those erected up to 1914 include:

1839: Stuttgart (the first open-air statue honouring an artist in Germany)

1857: Weimar (Goethe–Schiller dual statue)

1859: Jena; Marbach; Central Park, Manhattan

1861: Mannheim

1862: Mainz

1863: Hanover

1864: Frankfurt am Main

1866: Hamburg

1871: Berlin

1876: Ludwigsburg; Vienna

1886: Chicago; Philadelphia

1891: Columbus

1898: St Louis

1901: San Francisco (Goethe–Schiller dual statue)

1905: St Veit an der Glan (Austria); Omaha

1906: Wiesbaden

1907: Cleveland; Rochester; St Paul

1908: Detroit; Milwaukee

1909: Nuremberg

1910: Königsberg

1911: Syracuse

1914: Dresden

The events tended to follow a standard pattern (also described in the Introduction to this book), which typically involved festive processions; the honouring (laurel-wreathing) of a bust, statue, portrait, or other effigy; the reading of a eulogy and/or a poetic ode in the poet’s honour; choral singing; and/or a festive banquet. (For a good illustrated account of the 1859 Schiller event as it unrolled in Frankfurt, see Assel and Jäger 2011.)

The literary-political dimension

The 1859 centenary was, in a century of recurrent commemorations of the years of Schiller’s birth and death (1759 and 1805), particularly charged because it was the first middle-class civic demonstration of a pan-German nature since the failure of the 1848 liberal–national unification drive. For that reason, historians like George Mosse (1975) and Rainer Noltenius (1984) have tended to see it largely in a social-historical light, as a manifestation of the rise of oppositional social mobilization under nationalist auspices. Not only does the Schiller commemoration link the realms of the secular and the sacred; it also bridges the fields of culture and politics.

It was Schiller, rather than Goethe, who, as pointed out above, attracted the most fervent commemorative celebrations; this was partly because he fitted best into the Romantic-commemorative festive culture that emerged after 1814, and partly because Schiller was the more radical of these twin deities of German literature (see Dann 2001). He had, in his anti-authoritarian theatre, clamoured for freedom of conscience, Gedankenfreiheit (in his Don Carlos); he had glorified the liberationist messianism of Joan of Arc and William Tell. Schiller became a codename for the radical liberalism that was repressed in the German lands; and the poets who were moved to wrap themselves in Schiller’s cloak were often the more liberal-democratically minded ones, such as Uhland and Hoffmann von Fallersleben (whose commemoration in Breslau led to the establishment of a Schillerverein in that city in 1829).1

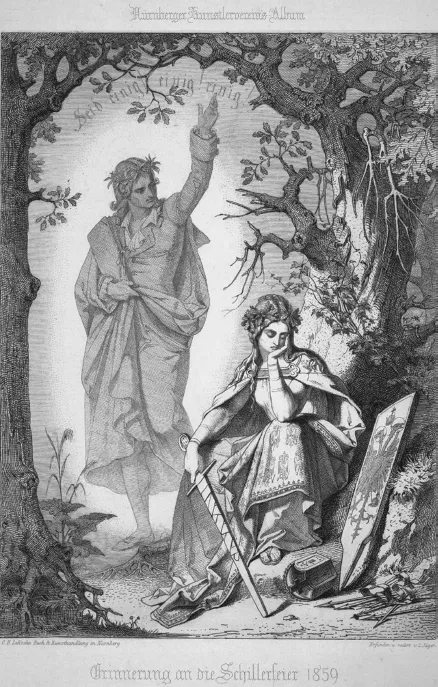

Commemoration was, then, not just a nostalgic or triumphalist celebration of past achievement, but also an attempt to retrieve from the past a message in danger of submergence (see Figure 1.2). Poems in commemoration of Schiller, often by poets who were themselves famous (such as Uhland, Hoffmann, or Mörike), thus constitute an interesting intersection between political rhetoric for use during a specific social occasion, and that more general principle in literary history which we call ‘influence’ or even ‘intertext’; witness, for instance, the volume of Schillerlieder von Goethe, Uhland, Chamisso, Rückert, Schwab, Seume, Pfizer und Anderen of 1839.2

Figure 1.2 The shade of Schiller exhorting a dejected Germany to be united. Allegorical engraving by G. Jäger on the occasion of the Schiller feast, 1859.

A specimen from the 1845 commemoration in Leipzig, by the leftist writer and scholar Robert Prutz (on whom see Bergmann 1997), may serve as an example. It relies heavily on the intertext of Wilhelm Tell (1804), with its almost Michelet-style, enthusiastic, and Jacobinian glorification of the Swiss insurrection. In particular Act IV, scene 2 is recalled when Attinghausen, on his deathbed, is vouchsafed a vision of the revolt’s future success, and breathes his last while urging inter-regional and inter-class solidarity: ‘Seid einig, einig, einig!’ This is how Prutz activates the Schiller text, giving it fresh meaning:

You see the signs flaming from the mountains

The Rütli oath still whispers in your ears

And hear what dying Attinghausen speaks:

The precious: Be united, united, united!

O realize that this applies to you!

The truth also needs its champions

And the victory of the spirit must also be won in battle

So be united for the struggle of this age

Be united, united for the people’s rights

Be united, united where liberty calls!

Then in you the poet’s spirit will awaken

And thus my friends this will be a true Schiller feast!

For all art is only flower and seed:

The true fruit of life is the deed.

(Quoted in Assel and Jäger 2009; emphasis mine)

‘Die wahre Frucht des Lebens ist die Tat’: This is more than the mere ‘echo’ or ‘influence’ of an inspiring, canonical author on later literary generations. While Hans Christian Andersen thematizes the transmutation of text (poem, tale, peal) into object (ore, bronze, bell, statue) and vice versa, Prutz turns the textual legacy and intertextual reverberation of Schiller’s theatre into political action.

Thus, the 1859 Schiller centenary not only continued earlier literary and cultural commemorations (such as the unveiling of the Beethoven statue in Bonn, 1845; see Storm-Rusche 1990) but, in its political charge, recalled the middle-class festivities which had begun to punctuate public life in Germany since 1814 (see generally Düding, Friedemann, and Münch 1988). The most famous of these are the 1832 ‘Hambach feast’ (which I only mention in passing here) a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on the Contributors

- Introduction: Fanning out from Shakespeare: Ann Rigney and Joep Leerssen

- 1 Schiller 1859: Literary Historicism and Readership Mobilization: Joep Leerssen

- 2 Burns 1859: Embodied Communities and Transnational Federation: Ann Rigney

- 3 Scott 1871: Celebration as Cultural Diplomacy: Ann Rigney

- 4 Moore 1879: Ireland, America, Australia: Ronan Kelly

- 5 Dante 1865: The Politics and Limits of Aesthetic Education: Mahnaz Yousefzadeh

- 6 Petrarch 1804–1904: Nation-Building and Glocal Identities: Harald Hendrix

- 7 Petrarch 1874: Pan-National Celebrations and Provençal Regionalism: Francesca Zantedeschi

- 8 Voltaire 1878: Commemoration and the Creation of Dissent: Pierre Boudrot

- 9 Vondel 1867: Amsterdam–Netherlands, Protestant–Catholic: Joep Leerssen

- 10 Conscience 1883: Between Flanders and Belgium: An De Ridder

- 11 Pushkin 1880: Fedor Dostoevsky Voices the Russian Self-image: Neil Stewart

- 12 Prešeren 1905: Ritual Afterlives and Slovenian Nationalism: Marijan Dovic´

- 13 Mácha, Petőfi, Mickiewicz: (Un)wanted Statues in East-Central Europe: John Neubauer

- 14 Cervantes 1916: Literature as ‘Exquisite Neutrality’: Clara Calvo

- 15 Whose Camões? Canons, Celebrations, Colonialisms: Paulo de Medeiros

- Index