- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Performance, Transport and Mobility is an investigation into how performance moves, how it engages with ideas about movement, and how it potentially shapes our experiences of movement. Using a critical framework drawn from the 'mobility turn' in the social sciences, it analyses a range of performances that explore what it means to be in transit.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

‘Three miles an hour’: Pedestrian Travel

In order to establish a context for this book’s focus on transport and mobility in performance, it seems necessary to begin with the form of mobility that occupies the most central place in twentieth and twenty-first century performance practices: walking. In this chapter, I am interested in the way in which discourses of walking – and of walking art in particular – set the terms of reference for other mobile practices. Ideas about speed, freedom, creativity, city, landscape, access and agency all become significant in a critical vocabulary because of the ways in which artists and others work through walking.

This chapter sketches out some of the broad contexts for thinking about walking before following a path through four themes that I suggest emerge from pedestrian travel: belief, retracing, resistance, and pace. My argument is that the well-established tradition of thinking, writing and performing the pedestrian yields a rich critical legacy that informs both theoretical and artistic explorations of other kinds of mobility. The experience of walking resonates in every other means of being on the move. Not only does it resonate, but it establishes a set of values and ideals against which the choice of mechanized transport is measured (and frequently found wanting). So my discussion of both the critical contexts and the four themes is intended to establish many of the lines of enquiry of the chapters that follow.

Critical contexts

‘In terms of the history of movement, walking is easily its most significant form, and is still a component of almost all other modes of movement’, writes John Urry in his study of mobilities (2007, p. 64). It is worth noting, then, that walking frequently complements, as well as offering an alternative to, other means of travel. The choice of pedestrian movement is often marked as deliberately antagonistic towards technological means of being transported, but in practice the various transports that we experience are caught up with one another in more complex ways than this antagonism would suggest. The fact that an overwhelming majority of the walking attended to in the critical discourse is undertaken as a choice also has implications that we should note. For the most part, Romantic poets, landscape artists, Situationists, ramblers, cultural geographers and flâneurs walk because they want to, not because they have to. The stories of those who walk because they are too poor to do otherwise are far less visible in the vast literature on walking. As Wrights & Sites note in their performative book of instructions, A Mis-Guide to Anywhere, ‘to choose to walk in the Mis-Guide way would seem strange to someone who daily has to carry water and firewood for long distances’ (2006a, p. 33). There is therefore a context of privilege in which most documented walking occurs, and a corresponding context of walking in poverty that needs to be acknowledged. In some places this is more apparent than others. Andie Miller, in the preface to her collection of stories about walking, notes that in South Africa ‘walking continues to be considered a practice of the poor and marginalised. And since the majority of the poor remain black, white pedestrians are regarded, if not with suspicion, certainly with curiosity’ (2010, p. xvii).

And there are some places where the pedestrian seems to disappear altogether; later in her book Miller, ‘as a non-driver’, reflects on Los Angeles as ‘the only place in the world where walking felt pathological’ (p. 11). Many walking artists position their work as a political response to the situation found in LA and, increasingly, elsewhere; walking is thus perceived as a radical choice in the face of cultural pressure to relinquish any prolonged contact between pavement and footwear.1

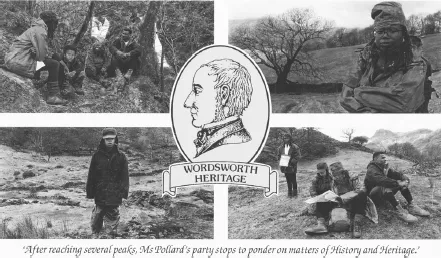

The radical potential of walking is a key theme in theoretical writing, featuring heavily in the works of Guy Debord and Michel de Certeau. These writers, along with Walter Benjamin, have created a pervasive critical apparatus, setting out the figures of the dérivist, the pedestrian and the flâneur as standard positions from which to theorize one’s walking. It is an apparatus that has become academically favoured – the accepted means of accounting for the role of the walker – and at least one of these three writers is likely to be employed in any discussion of walking in the arts, humanities and social sciences. One consequence that is immediately apparent is the shift of focus to urban settings. If the English Lake District is the privileged site of the Romantic walking tradition, Paris occupies this position in the critical tradition since the early-twentieth century.2 Benjamin, in his ambitious Arcades Project, famously draws upon the work of the nineteenth-century Parisian poet Charles Baudelaire to make claims for the significance of flâneurie as a practice of moving about the city, and carefully records his own routes around Paris after adopting it as his home in the 1920s. As Rebecca Solnit reminds us, it was Benjamin ‘who named Paris “the capital of the nineteenth century” and he who made the flâneur a topic for academics at the end of the twentieth’ (2001, p. 198). What Benjamin also did, as many responses to his work have noted, was to mark the walker as implicitly male, someone who walks alone, and who has the freedom and economic means to walk about the city at will.3 De Certeau’s role in the pedestrian canon was to establish a framework for analysing the relationship between power and resistance in the city (Morris, 2004). In his much-quoted essay ‘Walking in the City’ (first published in French in 1974 and in English a decade later), de Certeau set the terms for contrasting the strategies of the urban planner with the tactics of the pedestrian, and therefore for conceiving of the walking of ‘the ordinary practitioners of the city’ (1984, p. 93) as potentially subversive. His premise that walking is analogous with writing and speaking also paves the way for critical attention to the creative grammar of pedestrian practices, which has proved useful for scholars of performance. Debord and the Situationist International movement have been especially influential for those wishing to engage with political resistance through walking. Debord’s ‘Theory of the Dérive’ (first published in 1956) outlined a method, still much adopted by artists, of ‘drifting’ through urban spaces as a means of action against the capitalist ideology imprinted in the city. Together, Benjamin, Debord and de Certeau still dominate academic debates around what it means to walk. The critical discourse of walking also tends to be organized, albeit often implicitly, around two pairs of opposing terms: urban/rural and solitary/collective. That is to say, the claims made for pedestrian mobility frequently rest on its status as either urban or rural; similarly, different claims are made for walking depending on whether it is undertaken alone or as part of a group. The urban/rural pairing emerges from quite distinct genealogies. As Deirdre Heddon and Cathy Turner write in their research on walking women, ‘the represented landscape of walking as an aesthetic practice is framed by two enduring historical discourses: the Romantics and Naturalists, tramping through rural locations; and the avant-gardists, drifting through the spectacular urban streets of capitalism’ (2012, pp. 225–6). Still today, discourses of rural walking emphasize introspection, beauty, imagination and inner discovery, while discourses of urban walking focus on modernity, subversion and political comment. Though it can be tempting, especially in respect to contemporary car-dominated cities, to pitch urban walking against the ‘naturalness’ of rural walking, we should note that ‘being a leisurely walker in the so-called countryside is historically unusual behaviour’ (Urry, 2007, p. 77). Further, any perception of ‘natural’ countryside walking is even now demographically limited. The black British artist Ingrid Pollard’s Wordsworth Heritage (1992) (see Figure 1.1), a postcard image displayed on billboards around the UK, makes precisely this point. The mock postcard shows four images of the artist and her family hiking in the (historically over-determined) English Lake District, arranged around a ‘Wordsworth Heritage’ logo and accompanied by the line ‘After reaching several peaks, Ms Pollard’s party stops to ponder on matters of History and Heritage’. Pollard’s photographic project draws attention to the dearth of black pedestrians in narratives of rural walking, and cautions us to consider the ownership of various types and sites of mobility.

Figure 1.1 Ingrid Pollard, Wordsworth Heritage, 1992. Billboard poster. Courtesy of Autograph ABP

The solitary/collective pairing also inflects narratives of walking. Just as walking practices tend to announce themselves as either rural or urban, so they tend to be organized around championing pedestrian travel as either solitary or collective. Strong feelings for both states are recorded in the literature. ‘Now, to be properly enjoyed, a walking tour should be gone upon alone’ writes Robert Louis Stevenson in his 1876 essay ‘Walking Tours’. Benjamin’s flâneur and de Certeau’s pedestrian are also markedly alone, as are the Romantic walkers William Hazlitt (‘I cannot see the wit of walking and talking at the same time’), William Wordsworth (‘I wandered lonely . . . ’) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (in his Reveries of the Solitary Walker). In fact, however, Rousseau makes it clear that he remains solitary not through choice but through circumstance, and that this is not a state to be envied in ‘the most sociable and loving of men’. Nonetheless, the prevailing image of the Romantic walker is as a solitary figure.4 A corresponding image of the solo walking artist remains prominent, perhaps exemplified in Richard Long. Across almost 50 years of working by walking, Long has walked alone; the point of encounter with others is in the documentation rather than the journey. But there are alternative versions of walking art that prize the collective. Though many contemporary disciples of Situationism drift alone, Debord conceived the dérive as a shared form:

One can dérive alone, but all indications are that the most fruitful numerical arrangement consists of several small groups of two or three people who have reached the same level of awareness, since cross-checking these different groups’ impressions makes it possible to arrive at more objective conclusions. (2006 (1958), p. 63)

This claim to objectivity is not often repeated; elsewhere, walking with is more likely to be valued for the opportunities it offers of talking to. Misha Myers’ (2010) approach to walking as ‘conversive wayfinding’ is one example, as is Heddon’s (2012) ‘Turning 40’ project (in which she undertook 40 walks with friends), with its focus on companionship and the ‘side-by-side’ rather than ‘face-to-face’ encounter. So claims are made for collective walking in terms of objectivity and sociability. They are also made in relation to power: collective walking is an enduring form of protest, found in both rural and urban situations (examples include the Kinder Scout mass trespass of 1932 and anti-government marches in Egypt in the summer of 2013).

Throughout the writing and performance in this vast field, ‘walker’ is a broad term that encompasses a wide variety of approaches to, and reasons for, travelling on foot. The walker, as we have seen, is frequently theorized as flâneur, dérivist or pedestrian. Elsewhere, the walker is figured as pilgrim, hiker, wanderer, activist, stroller, climber, migrant, nomad and tourist, among others.5 Further, walking art constructs a number of different modes of encounter: the artist walks and reports back;6 the spectator walks, guided by the artist in the form of recorded voice, written instructions or ‘smart’ technology; spectators walk with the performers, experiencing sections of performance en route. Across all of these discourses, figures and structures, I suggest that the themes of belief, retracing, resistance and pace recur, emerging as guiding ideas that inflect every other experience of travel.

Belief

When the writer and performance-maker Phil Smith writes ‘I am a great believer in walking as far more than physical exercise’,7 he is expressing something akin to spiritual belief, and it is a belief that has many historical precedents. Walking, as we know from Rousseau, might be a spur to meditation, and certainly elicits zeal from its followers. Rebecca Solnit, despite the clear personal attachment to walking documented in her book Wanderlust, urges us to be wary of some of the grander claims made in this regard, citing with suspicion an example that asserts that ‘perhaps walking can be the way to peace in the world’ (2001, p. 124). More than any other type of movement addressed in this book, walking is undertaken for pleasure as well as for travel, and is therefore conceived by some as a life choice rather than, or as well as, a means of getting from A to B. And it is as a life choice that walking becomes associated with values of truth and authenticity. This has a spiritual dimension, but also a fundamentally physical one, in terms of the physical contact (footwear aside) between a walker’s feet and the ground. The geographer Peter Adey comments on this connection:

For all the buffering shoes and boots achieve, a long history of writers and thinkers consider walking to be the only true and authentic engagement with nature, the environment and landscape. Others remind us how the horse-as-mediator distances one from the landscape because it is an inflexible arrangement. Walking is pleasurable because it is autonomous. (2010a, p. 204)

Walking is prized for its directness: it seems to offer an unmediated encounter between environment and traveller. It enables a contact with the elements – with open/fresh air and changes in weather8 – that many other modes of transport prevent with barriers of glass and metal. For Solnit, it engenders a feeling of embodiment that she contrasts with the disembodiment produced by ‘automobilization and suburbanization’ (2001, p. 267). An important aspect of the belief that I am pointing to here is the connection made between physical contact and self-knowledge, for ‘walking is also proposed as an activity that enables us to stay in contact with ourselves’ (Heddon, 2008, p. 105).

If there is a strand of belief in discourses of walking, then it arguably finds its clearest expression when the walk is conceived as pilgrimage: a journey to a physical place intended to yield greater spiritual understanding. Pilgrimage, as Solnit points out, ‘is premised on the idea that the sacred is not entirely immaterial, but that there is a geography of spiritual power’ (2001, p. 50). She notes, too, that pilgrimages nowadays frequently involve the use of other modes of transport (cars and planes), but still the symbolism of the journey relies on some element of walking. Alongside the guided tour, the pilgrimage emerges as a fertile model for walking artists.9 Hamish Fulton and Richard Long, two pioneers of walking art, both adopt tropes of pilgrimage in their work. As I write, the poet Tom Chivers is leading one of a series of performance events in London under the title The Walbrook Pilgrimage, following the route of a buried river. The structure of pilgrimage – or at least walking as a ritual act of belief – is also there in Carl Lavery’s Mourning Walk (2006), a performance documenting a walk made to mark the death of Lavery’s father. The work combines an account of Lavery’s (solitary, rural) walk with memories of a series of significant moments in his relationship with his father. In the performance text, Lavery reflects on a Celtic belief associated with death:

I feel there is much to be said for the Celtic belief that the souls of those whom we have lost are held captive in some inferior being, in an animal, in a plant, in some inanimate object, and thus effectively lost to us until the day (which to many never comes) when we happen to pass by the tree or to obtain possession of the object wh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Three miles an hour’: Pedestrian Travel

- 2 ‘Nothing is moving’: Railway Travel

- 3 ‘Motorvating’: Road Travel

- 4 ‘A place without a place’: Boat Travel

- 5 ‘Alone at last’: Air Travel

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Performance, Transport and Mobility by F. Wilkie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.