eBook - ePub

The Rise of Multinationals from Emerging Economies

Achieving a New Balance

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Rise of Multinationals from Emerging Economies

Achieving a New Balance

About this book

The 41st Annual Conference of the Academy of International Business UK and Ireland Chapter was held at The University of York in April 2014. This book contains records of keynote speeches and special session on key topics, as well as selection of some of the best papers presented at the conference.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Rise of Multinationals from Emerging Economies by P. Konara, Y. Ha, F. McDonald, Y. Wei, P. Konara,Y. Ha,F. McDonald,Y. Wei,Kenneth A. Loparo,Kenneth A. Loparo,Charles P.C. Pettit,Patrick Dunleavy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Keynotes and Panel Sessions

1

Keynotes

Peter Buckley and Jean-François Hennart

This chapter presents the keynote speeches delivered by Peter Buckley (University of Leeds) and Jean-François Hennart (University of Tilburg) in the Academy of International Business, UK and Ireland Chapter Annual Conference in April 2014. The session was chaired by Yingqi Wei (University of Leeds) (co-chair of the conference).1

Buckley on ‘historical research methods in international business’

Good morning, it is a particular pleasure for me to be here because I am a graduate of York University. It is also appropriate that I am talking about historical research methods because of course I did my degree a long time ago. When I was here last time, I went to look for the university that I knew and it is buried in a much bigger institution, but it is a pleasure to be here and at the annual conference of AIB UKI. I am talking today about something rather different, or something completely different, as Monty Python might say: Historical Research Methods in International Business.2

I’ve always had an interest in history, and I read a lot of history, which shows what a sad individual I am. It occurred to me that the methods that history used and the methods that international business use have a lot in common and I was looking for issues that are relevant and where we can draw from what historians have done. History and international business are very different subjects as we will see, but what I am trying to do is to look at the parts of historical research and the methods of historical research that can be relevant to international business. So, I thought I would start off on a really positive note! Here is one from Kogut and Rangin (2006): ‘For the general public methodological discussions are tedious. Worse – methodologists often render interesting topics into lifeless entities’. So, I propose to give a really tedious talk and make it as lifeless as possible!3

Just to mention a few points about the kind of philosophy that underlies the way that historians approach research. Historians (and international business scholars) have very different views (on some key concepts), especially about causation. Historians and social scientists including international business take very different views about causation, such as what is endogenous and what are the dependent and independent variables. And the whole approach of history is actually very different as we will see.

One of the phrases that is used of historical research methods is the difference between ‘cartography’ where you are trying to be very precise and produce a precise map of history and what happened, versus ‘landscape painting’ where you are trying to give a general overall impression of what happened and trying to obtain a picture of the reality, in the way that an artist sees a landscape. Here you can see the difference of approaches that historians take. Some historians want to be very precise and measure things as we will see. Cliometrics and economic histories are of this type. Other historians want to give an overview and insight – and sometimes an idiosyncratic insight.

Path dependency is a very important issue for both historians and international business scholars. A lot of people have written about path dependency, and this is one of the areas of very deep water that I find myself getting into. There are lots of really important things being written on path dependency with equations that take up pages about how sensitive events are to initial conditions and what makes the difference.

The final thing is propulsion and periodisation – that can be translated as what leads to growth and how we decide particular époques, how do we put things in different periods, which is very important to historians in defining themselves. So, those are some of the underlying philosophical issues that arise with regard to both history and international business.

I wish to focus on some of the methods of history that I think are important to international business. I hope it is relevant to our own work in international business. I will focus on sources and analysis of texts, time series analyses, comparative methods, counterfactual analysis, the unit of analysis and finally one which is a bit of a catchall – history, biography and the social sciences, which is about the relationship between individuals and wider causes. I think all of these issues from (the discipline of) history have relevance to international business.

The first point is the sources and analysis of texts. When historians think about text, not only are they necessarily talking about a written piece of information. They could also be considering oral history, about the way people explain their lives or the issue that we are talking about and on how reliable are eyewitness accounts. Historians have spent a lot of time on this because there are stories, particularly of battles, where an individual was involved in a battle. We might think the best way of explaining a battle is to go to and see what an individual thought about that battle. It doesn’t need much imagination to see that an individual in a battle may be one of the worst people to explain what happened because the fog of war may make their record of the battle not be relevant to the overall issues of how the battle was fought. Is that at all relevant to the way that we international business scholars look at how managers view the battles they are part of? Does a manager see the whole of a battle? Do we often take a manager to be all-thinking and all-seeing and take their word as given? Is that right? We may also consider artefacts – the Bayeux Tapestry is one of the best sources about the conquest by William the Conqueror over Harold, so we have got a wide range of sources that we could use to consider big defining events.4 Do we in international business necessarily always use all possible sources including artefacts, and, if we do, how much authority do we give to them? Should we be investing in these ‘artefacts’ sources that we use – interviews of managers, texts of managers, company reports, whatever we call them with authority? Historians ask questions of their artefacts – what is their provenance, and how internally reliable are they? Do international business researchers always ask these types of questions of the ‘artefacts’ that they use in their research? Typically, historians will ask of a text some key questions. When was it written or produced? Where was it written or produced? By whom? What pre-existing material was there? Has it got integrity? Has it got credibility? And I have added one, which is the translation issue. When we translate as we do in international business, how reliable is the translation? So, we have a whole set of questions. When we approach evidence, when we present evidence, are we as rigorous as we should be in asking all those questions of the evidence that we get? And finally what about the material that is not in archives? If we are business historians, as some of us in this room are, we could look at the archive. (For example,) we could look at the archive of Marks & Spencer’s on Leeds University campus. We could go into the archives, but of the materials that are included in the archive, how much of them depict the whole of the story? There has been a lot of work done in history on what has been called ‘subaltern studies’. When you look at the story of India, for example, who wrote that story? The Raj, or the British essentially wrote the story of India but they only wrote certain Indians into the story and others were left out. So historians have spent time trying to look for evidence that is outside the archive as a criticism, as a counterweight. Perhaps we in international business should be doing that as well.

Time series analysis: there is a whole lot to say about this, but I have time for only a brief overview of this complex issue. Of course, historical variation is one of the most important things in international business. There have been stacks of articles in, for example, Journal of International Business Studies (JIBS) about endogeneity, methods from history, economic history, computerable general equilibrium models, longitudinal qualitative research and all methods on which we could draw. There is an interesting quote from British philosopher and historian Isaiah Berlin: ‘history details differences amongst events, sciences focus on similarities’. We are often looking for regularities. However, there is an argument that perhaps it is the differences, the outliers, the non-standard things that we should also be looking at. My argument would be we should pay a lot of attention to the way historians have dealt with differences between events in the past.

Comparative methods are absolutely central to international business. The very word ‘international’ means ‘comparative’, you are comparing nations in this case. Nations are not always the right measurement as we will see in a minute. There are three key measures that we can take – all of which are used in history. The first comparative method includes the comparison across space – for example, to compare the IBM subsidiary in America with its subsidiary in India at a point in time. Then there are comparisons over time, so that we may look at the growth/decline in IBM’s subsidiaries in different locations over time. Finally, there is the counterfactual, controversial issue of asking ‘what if?’ What if IBM had not done certain things? What if Tata had not bought Land Rover? So, the issues of comparison across space and over time and counterfactual comparisons are absolutely central to international business studies.

The second comparative method is natural experiments, where we can actually look at a situation where the experiment has occurred in the real world. One of the classic examples of this was a study by Kogut and Zander of the Zeiss company. Zeiss, a German company, was split in two by the Iron Curtain. So, you can compare Zeiss in East Germany with Zeiss in West Germany, and we have a natural experiment where there is the same starting point, the same company in a different context. It would be absolutely wonderful if you could find examples of those kinds of real world examples – of a company with the same starting point but with some sort of a split that leads to different trajectories from the starting point. Normally, international business scholars will compare subsidiaries in different countries and hold constant a lot of the things that are likely to affect subsidiary behaviour and outcomes. This is statistical control rather than experimental control. Typically, international business scholars use statistical control. We measure things via statistics, but experimental control is a more rigorous and sometimes more revealing method of controlling for different conditions. We cannot always use the experimental method but, where we can, we can have different means of controlling for other factors likely to affect behaviour and/or outcomes.

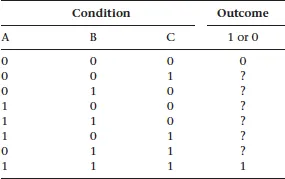

The final thing is about qualitative comparison. This comes from an ancient British genius named George Boole, who invented this way of thinking about comparison.5 So let’s say we have the argument that there are three causes leading to an effect. Let’s say we are going to argue that Japan developed rapidly because it had business groups, company unions and the zaibatsu system. How do we prove this? Let’s see Table 1.1. We need cases where one or two of those things are relevant. If none of them are relevant, we need a case where none of them occur and presumably the outcome is zero. Indeed, we actually need eight cases to be able to show that these three events were the reason for the outcome. So, if the outcome is one, the three events are on the bottom line and we need that whole array. That helps us in designing case studies. I often get this question: how many case studies do I need? How many students have come and asked you that? Well, here is a possible answer. If you have got three causes, you need eight cases with all those different factors. So, you don’t have to do thousands and thousands of cases. If you can choose your eight cases, you have got a case for your argument.

Table 1.1 Truth table for a three cause proposition

Now I would like to move on to counterfactual analysis, the ‘what if’ question. This is another area where I rather fell into a big argument. There is a book called Archduke Franz Ferdinand Lives! A World without World War I.6 This is a counterfactual history. It is an attempt to work out what would have happened if the bullet had missed him (Archduke Franz Ferdinand) in Sarajevo. World War I would not have happened. If World War II would not have happened, Hitler would not have controlled the Third Reich and the Holocaust would not have happened and so on. Here is another book that criticises counterfactual history – it is called Altered Pasts: The Counterfactuals in History.7 The book has the image of an astronaut on the moon and the Chinese flag on his right side. So, what would have happened if China had landed on the moon, not America? Counterfactual history can be absurd as, for example, Niall Ferguson’s recent BBC programme on what would have happened if Britain had not entered World War I. There are also all kinds of issues raised in counterfactual history about the role of individual agency and about the deep causes of large and significant events. There are, however, some less ambitious attempts in business history to look at the historical alternatives approach: The argument, for example, that technological determinism may not be as strong as business historians typically take it to be. For those of us who are fairly long in the tooth, we can remember the alternative position, the argument about what would have happened if a firm from country A had not invested in country B. There is a lot of work on that, and this goes back to Fogel’s analysis of American railways where he was asking the questions about what would have happened if the American railways had not been built, whether growth would have been as fast, and so on.8 What Fogel did was to specify an alternative where a system of canals did the work that was actually done by the railways. Another wonderful attempt at doing this is Mark Casson’s alternative railway system for the UK, complete with timetable. This is not about imagining lots of changes. It is actually using an alternative by more carefully specifying what did happen, and I think that is far more acceptable than the rather wild assertions of alternative history based on grand and sweeping generalisations, which is common in much of literature on contemporary history.

Let me consider next the issue of the unit of analysis. We have huge issues in international business about the unit of analysis. So do historians. Historians have looked at all kinds of different levels global history, national history, and so on. A relatively recent fashion is micro-history, looking at very small units, peasant communities and small communities to try to look at what happened to them and to create the sort of total history on a micro scale. We have exactly the same type of problems. The list here is actually from a paper I did with Don Lessard from MIT Sloan School of Management. We looked at different levels of analysis: manager, subsidiary, firm, economy, region, world economy and we might add to that the network and the value chain. If we are looking at one of those levels, how do we control for the others, how do we look at interactions, and what is the right level to look at the causation we are searching for? These are really important questions in specifying a setup of research and a doctoral thesis.

Another unit of analysis issue links somewhat to the what if thing because the what if thing is often about a great man, it usually is a man, it’s not very often a woman, a great man, say Napoleon. What would have happened if Napoleon had lost? What would have happened if Franz Ferdinand had not been shot? Historians tend to attribute a great deal to individual agency. International business scholars have the same tendency. We have a tradition of attributing things to heroic businesspeople. Richard Branson comes to mind. This raises the question – what is the role of individual agency versus underlying forces? A very profound and a very important question. I could not resist this one: An example of the best of the best. This is from a sports history showing just how incredible some individuals are in the arena of sport. Some people will make the argument it is just the same in business: there are some people who are so much better than everybody else. I am not sure I believe it, but I am going to put forth the argument that some people are so much better than everybody else that they really change things. That score of Bradman is unbelievable, 4.4 standard deviations above the mean of test cricket as batsmen!9 That is phenomenal. Of course, it is an accident of history that Bradman was not an Englishman, but accidents do happen. So, what is the independent variable? Is it individuals who make a difference? How do we specify the independent variable? If we have very sensitive dependence on initial conditions, maybe individuals can a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: The Rise of Multinationals from Emerging EconomiesAchieving a New Balance

- Part I Keynotes and Panel Sessions

- Part II Rise of EMNEs

- Part III Performance/Survival in DMNEs in Emerging Economies

- Part IV Coming In and Going Out: Dynamic Interaction between Foreign and Local Firms

- Index