eBook - ePub

The European Union in a Multipolar World

World Trade, Global Governance and the Case of the WTO

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The European Union in a Multipolar World

World Trade, Global Governance and the Case of the WTO

About this book

Presenting a critical overview of what 'emerging multipolarity' means for the world's foremost global trading bloc and economic power, the European Union, this book offers new insights into how the rise of the emerging economies has impacted the EU and its role within the World Trade Organization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The European Union in a Multipolar World by M. Dee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Emergence of a Multipolar World

Abstract: The world of today is witnessing the rise of new and diverse global powers capable of wielding influence in both global markets and global governance. Multilateralism has become increasingly difficult, yet never more important. Diplomacy has a renewed significance. This is an emerging multipolar world. In this introductory chapter the concepts and debate on an emerging multipolar world are developed and considered. Setting out the book’s main aims, outline and principal arguments, this chapter offers an important overview of what an emerging multipolar world might mean for the world’s foremost global trading bloc and economic power, the European Union.

Dee, Megan. The European Union in a Multipolar World: World Trade, Global Governance and the Case of the WTO. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137434203.0005.

Introduction

There is little doubt that the world is a very different place today than it was 30, 20 or even 10 years ago. The end of the Cold War was to bring with it both shrinking borders and new power brokers; closer interdependence and greater global insecurities. Globalisation has brought the abroad ever closer to home. Power is diffuse. Gone are the days when the ‘West’ could dictate policy and shape the world in its own image. The world of today is instead witnessing the rise of new and diverse global powers capable of wielding influence in both global markets and global governance. The wealth of the economic powerhouses of the latter half of the 20th century, including the United States, Europe and Japan, has begun to wane, while the global south is on the rise, not least in the form of the emerging economies, China, India and Brazil. Multilateralism has become increasingly difficult, yet never more important. Diplomacy has a renewed significance. This is an emerging multipolar world.

For observers of international politics the interaction of ‘poles’ – that is, the ‘great powers’ – in the world has been a topic of interest since Thucydides first posited that, ‘the strong do what they will and the weak suffer what they must’. Great powers, and the balance of power between them, are topics at the core of both scholarly theory and policy debate and, though the world may be changing, the importance of power has not. While the emergence of a neo-Westphalian system is now speculated – with the growing influence of international institutions, markets, civil society and transnational corporations seen to be shaping the world as never before (Dennison et al., 2013, 4; Held, 2010; Setser, 2008) – states and, as in the case of the European Union (EU), unions of states still constitute the main units of power within the international system. Understanding how global reordering and the changing dynamics of an emerging multipolar world order impact the behaviour of states within the international system is thus of continuing and ever increasing importance.

It is to these issues and the broader impact of a changing world order that this book is aimed. Specifically, this book is interested in how the emergence of a multipolar world is impacting the behaviour and role of one particular actor – the EU. Considered to be something of a sui generis global actor, and power, the EU is perhaps an unusual candidate of focus in a book dedicated to the subject of global reordering and multipolarity. However, as this book shall highlight, the changes that have taken place within the international system since the end of the Cold War have been largely economic in character. Despite its idiosyncrasies as a global actor, the EU is, by any definition, a ‘pole’ within the global economy and a powerhouse of the multilateral trading system. With 28 member states and a population of just over 500 million people, the EU remains today one of the world’s largest, richest, single markets. Speaking with one voice in its external trade and commercial policies, the EU has also wielded considerable influence within global economic governance, not least in the case of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The emergence therefore of a multipolar world – particularly a multipolar trading world – has had, and will continue to have, important ramifications for this great economic power.

Such ramifications are already being made manifest. While some project optimistic forecasts that the EU’s unique political make-up, international identity and ‘multilateral genes’ (Jørgensen, 2009, 189) make it well-suited to tackle the new dynamics of a changing world order (Santander, 2014, 70; McCormick, 2013; Leonard, 2005), others have increasingly lamented the EU for its fall from influence and decline within international politics, the global economy and in systems of global governance (Webber, 2014; ECFR, 2014; M. Smith, 2013; Dennison et al., 2013; Whitman, 2010; Fischer, 2010). Within the WTO – an international institution established in 1995 largely in response to EU and US demands – the EU’s power and position have particularly been brought into question (Ahnlid & Elgström, 2014; Young, 2011; Dür & Zimmerman, 2007), with the seemingly failed or failing WTO’s Doha Round of multilateral trade negotiations frequently cited as example of how an emerging multipolarity is negatively impacting global governance and the influence of the EU within it (Webber, 2014; M. Smith, 2013, 661; Peterson et al., 2012, 8; Gowan, 2012; van Langenhove, 2010, 12). Widely associated with the rise to prominence of the emerging economies and their increasing influence within the multilateral trading system (i.e. Economist, 2009), the EU’s perceived decline as a global trading powerbroker does raise several critical questions about its response to, and role within, an emerging multipolar world.

In particular, these contrasting expectations of the EU’s role in a changing world present something of a puzzle. Why, if the EU is expected to be a pole best suited to an emerging multipolar world, has it been seen as a declining power with a diminishing relevance and performance in systems of global governance? More than this, it raises the question explicitly of how the EU has been influenced by the emergence of a multipolar world, and why claims have reverberated of the EU’s perceived fall from grace.

In responding to these research questions this book shall present the following core arguments. First, the EU has experienced a substantive shift in its role positioning and performance within the WTO and multilateral trading system since the Doha Round of multilateral trade negotiations was launched in 2001. Moving from a proactive, and reformist pusher and leader in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the EU has since transformed its approach to play a variety of different roles including defender, mediator, laggard, cruiser and bystander.

Second, rather than being a reflection of a Europe in Decline, the changes in the EU’s role within the Doha Round are evidence of a Europe in transformation. Reflecting pragmatism in dealing with the changing dynamics of the international system, the EU’s strategic reorientation and its more reactive roles within the Doha Round in favour of bilateral and regional trade agreements have demonstrated the EU’s increasing ability to broaden its role-set to adjust to the new geopolitical reality of a multipolar world.

Third, the EU’s role in a multipolar world going forward should be considered less as the EU being a unique and ‘different’ type of actor or power, but rather as the EU acting as any other pole. In this respect a shift in focus away from the Power Europe (Normative, Civilian, Ethical, etc.) debate, which has tended to position the EU in a narrow role-set of a proactive and reformist role model for others to follow, is recommended. Instead focus is directed towards a broader reconceptualisation of Pragmatic Polar Europe which addresses the EU’s capacity to adopt a multitude of roles, across a multitude of negotiation forums, in order to practically and strategically adapt to a changing world.

Highlighting the concepts and debates surrounding the issue of global reordering and multipolarity, and the EU’s place as a ‘pole’ in today’s international system, this chapter thus sets the scene for the book in its assessment of the EU in an emerging multipolar world. In so doing the chapter is broken into four sections. Section 1 addresses the concepts and debate surrounding the emergence of a multipolar world. In Section 2 the changing dynamics of a multipolar international system are outlined with specific reference to its implications for global governance and multilateralism. In Section 3 focus is turned to the EU itself, addressing its make-up as a global actor, and power, and elaborating upon the contrasting expectations of what a multipolar order will mean for the world’s largest trading bloc. Section four then provides a brief justification for focusing specifically on the WTO and its Doha Round along with an overview of the chapters to follow.

The emerging ‘multipolar’ world

A multipolar international system exists where there are ‘a number of states wielding substantial power in the international system; there are a number of “great powers” ’ (Young, 2010, 3, see also Haass, 2008, 1). In a multipolar world order, ‘several major powers of comparable strength ... cooperate and compete with each other in shifting patterns’ (Huntington, 1999, 35). Multipolarity is distinctive from a bipolar system which has just two great powers of roughly equal size and capability (Mearsheimer, 2001, 269–70), whose relationships, alliances and behaviour are central to international politics (Huntington, 1999, 35). It further differs from a unipolar system which consists of just one great power (or ‘hyper power’1), ‘whose capabilities are too great to be counterbalanced’ by any other state in the system (Wohlforth, 1999, 9).

It is an undisputed fact that the end of the Cold War brought an end to a bipolar world order that had existed for over 40 years, dominated by the United States and Soviet Union, and established, for a time, a unipolar world dominated by the United States as the world’s only superpower. The unparalleled power capabilities of the United States and its pre-eminence following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 have been well documented (Ikenberry et al., 2009; Jervis, 2006; Ikenberry, 2001; Wohlforth, 1999; Huntington, 1999). Nearly three decades since the end of the Cold War and the United States continues to demonstrate an enduring preponderance. Spending nearly as much on its military and defence as the whole of Europe and East Asia combined,2 the United States is the only power in the world with the capacity to sustain a global military force (Mearsheimer, 2010), and it possesses nearly half of the world’s operational nuclear warheads (SIPRI Yearbook, 2013, 12). In economics and technological development, the United States is a global leader. It is moreover a truism that the United States has had an unprecedented political influence on the creation, and landscape, of today’s world order, not least in terms of the international institutions it sponsored and helped establish after World War II (Vezirgiannidou, 2013).

Despite its preponderance, the longevity of the United States’ ‘unipolar moment’ (Krauthammer, 1990) has nevertheless come under some scrutiny (Layne, 1993). A burgeoning debate has begun to focus upon whether the world is now witnessing the emergence of a multipolar world order (Wade, 2011; Held, 2010; Hiro, 2010; Moravcsik, 2010, 154; Drezner, 2007), in which several centres of power or ‘poles’ exist. In sharp contrast to the proponents of unipolarity who espouse the military superiority of the United States, those arguing that a multipolar world order is emerging have focused instead upon the growing economic powers, and particularly, the emerging economies, or BRICS3 – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (NIC, 2012; Wade, 2011; Held, 2010, 2–3; Young, 2010, 3; Moravcsik, 2010, 154; Drezner, 2007).

In this emerging multipolar world, power is perceived to be more diffuse (Haass, 2008). No longer assessed solely on the grounds of military hard power; the ‘great powers’ of the 21st century are being assessed on their global shares of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), their competitiveness in global markets and their shares of world trade (see Held, 2010, 2; Young, 2010; Drezner, 2007). Global economic and demographic trend reports are becoming polarity calculators (see IMF, 2013; NIC, 2012, 2008). More than this, while power in this emerging multipolar world continues to be seen in part as a calculable asset, assessed in terms of economic strength, population (and thus market) size and technological capabilities of the major economies, it is also being associated far more with political influence in systems of global governance (Young, 2010, 3).

Conceptualisations of power are thus increasingly being understood in relational terms, whereby, ‘A has the power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would otherwise not do’ (Dahl, 1957, 202–203; see also Strange, 1994, 25; D. Baldwin, 2013). As a consequence, power, and the great powers, are today being identified not only as those actors with (or the potential to have) great material resources, but as those who are able to influence decisions and shape outcome within the international system and, most particularly, in international institutions. The fact that, by 2025, China and India are expected to have the world’s second, and fourth, largest economies, respectively (NIC, 2008, iv; IMF, 2013), and that the developing economies are likely to outpace both the export and GDP growth of the developed economies by a factor of two or three in the decades ahead (WTO, 2013a, 45), are trends expected to impact not just the wealth, and power, of the world’s current global leaders – the United States and the EU – but also the global balance of power in political decision-making.

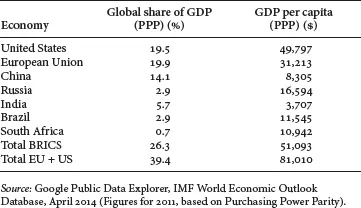

While the United States continues to dominate the global landscape as the world’s largest military power, in economic and geopolitical terms an emerging multipolarity is now revealed in which the United States, the EU and BRICS (particularly China, India and Brazil as the leading BRICS import and export nations) are its key poles and with a growing number of middle or intermediate powers rising through the ranks. In this emerging multipolar world the balance of power is, however, unevenly distributed. As Posen (2009, 348) argues, ‘polarity is not synonymous with equality ... The great powers themselves vary in their capabilities’. While trends indicate that a more balanced multipolar world order may well emerge in the decades ahead (NIC, 2012), the current multipolar system is unbalanced (see Mearsheimer, 2001, 44–45) with the United States and the EU still largely superior to the BRICS in economic, military and political clout. As reflected in Table 1.1, in global shares of GDP – a useful indicator of the overall output of an economy – the United States and the EU today each account for nearly 20 per cent, compared to a combined BRICS share of 26 per cent. In terms of relative wealth moreover – an important indicator of the standard of living in each of the world’s economies – the United States and the EU have by far the largest GDP per capita (at $49.8k and $31.2k, respectively) compared to a combined BRICS tally of $51k.

In global competitiveness – an index calculated across a variety of pillars including, for example, labour market efficiency, infrastructure, higher education standards, social institutions and market size – the United States ranks fifth in the world while five of the EU’s member states sit in the top ten rankings.4 China, in comparison, ranks 33rd in the world, while South Africa, Brazil, India and Russia rank between 53rd and 64th (World Economic Forum, 2013, 15). In terms of status moreover, China, India and Brazil continue to be identified as developing countries.5 Despite China’s vast market size with a population of 1.3 billion, 128 million of its citizens continue to live below the poverty line (World Bank, 2014a). In India, one third of its 1.2 billion population lives in poverty (World Bank, 2014b). By contrast, the United States and the EU’s member states are industrialised, classified as developed countries and high-income economies. Such asymmetry of wealth, competitiveness and status between the major powers6 does therefore make it important not to over-exaggerate claims of dramatic changes in the global balance of power (see also Young, 2010, 12).

TABLE 1.1 Global economic indicators of the major powers

And yet, the changing dynamics of today’s global economy, most notably with regard to world trade, have enabled the emerging economies to exert a growing influence which requires closer analysis and better understanding. In the past 30 years global trade has undergone substantive changes. World merchandise and commercial services trade have increased, on average, by 7 per cent every year. Betwe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Emergence of a Multipolar World

- 2 The EU in a Multipolar World: A Framework of Analysis

- 3 The Evolution of the EUs Global Trade Agenda: Transforming Role Position in the WTO

- 4 The EUs Changing Role Performance in the WTOs Doha Round

- 5 Meeting the Challenge of a Changing World

- Bibliography

- Index