eBook - ePub

Minimum Wages, Collective Bargaining and Economic Development in Asia and Europe

A Labour Perspective

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Minimum Wages, Collective Bargaining and Economic Development in Asia and Europe

A Labour Perspective

About this book

This book offers a labour perspective on wage-setting institutions, collective bargaining and economic development. Sixteen country chapters, eight on Asia and eight on Europe, focus in particular on the role and effectiveness of minimum wages in the context of national trends in income inequality, economic development, and social security.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Minimum Wages, Collective Bargaining and Economic Development in Asia and Europe by Maarten van Klaveren,Denis Gregory,Thorsten Schulten in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Asia: A Comparative Perspective

Maarten van Klaveren

1.1 Commonalities and differences

In this chapter, we set out the characteristics of the eight Asian countries (China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Thailand and Vietnam) scrutinized in the following chapters. The focus is on minimum wages (MWs), collective bargaining and economic development. We start by positioning the countries according to their gross domestic product (GDP) per capita ranking and growth rates since 2000. In section 1.2, we explore the patterns and differences in inequality and informality. In particular, we focus on the development of the wage or labour share and the personal income distribution coming through in the last decade. Section 1.3 covers MWs and collective bargaining, as well as the linkage with social security systems.

In 2013, the eight countries in total had a 3,240-million-strong population, accounting for nearly half (47.5%) of the world’s population. They include four of the world’s most populous countries: China (no. 1), India (no. 2), Indonesia (no. 4) and Pakistan (no. 6). Measured in terms of GDP (current prices in US dollars), in 2013 they comprised three of the largest economies in the world, namely China (no. 2), Japan (no. 3) and India (no. 10). That said, the GDP total of these eight made up just over one quarter (25.3%) of the world’s total GDP. This reflects the fact that four of the countries we studied are, according to World Bank criteria, in the lower middle-income (LMI) range. With their GDP per capita between USD 1,000 and USD 4,000 in 2013, Indonesia at USD 3,475; Vietnam at USD 1,911; India at USD 1,499; and Pakistan at USD 1,299 all qualified as LMI countries. By contrast, two of the countries we studied belong to the ‘advanced economies’ category (countries with per capita incomes above USD 12,000), namely Japan (USD 38,492 in 2013) and Korea (USD 25,977), while China (USD 6,807) and Thailand (USD 5,799) (according to the World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) database) currently belong to the emerging economies (EEs) category with per capita incomes between USD 4,000 and USD 12,000.

Considerable variation also shows up in economic growth rates. The available GDP per capita growth figures over the last 13 years (Statistical Appendix, Table A.2) confirm that China at nearly 10 per cent displayed by far the highest average annual GDP growth rate, followed by India and Vietnam with over 5 per cent. Indonesia, Korea and Thailand also showed considerable long-term growth figures. Pakistan was somewhat slower than these six, but its 10-year average growth rate remained above those of most European countries scrutinized in this book. Japan, the most mature economy of the eight, lagged far behind, with less than 1 per cent average annual GDP growth – a phenomenon analysed later in Chapter 5. Table A.2 also reveals the convergence since the 1990s between the advanced economies, the EEs and, to a lesser extent, the LMIs. During 2004–13, the eight Asian countries showed an annual average GDP per capita growth of 4.4 per cent, against an average of just 0.5 per cent growth for the eight advanced Western-Middle European countries we studied. The four Central and Eastern (CEE) countries we selected showed an annual average of 2.9 per cent growth rate while Russia, boosted by 8 per cent annual increases during 2004–07, showed a considerable 4.2 per cent average growth rate.

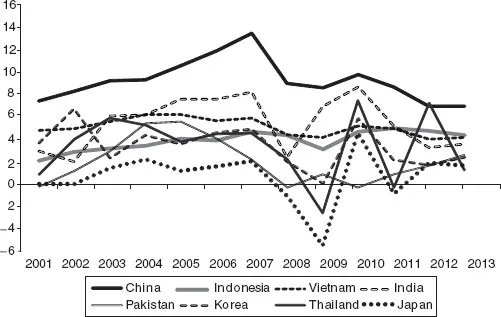

The recent development of national income, that is GDP, in Asia has often been highly volatile. As Figure 1.1 (based on Table A.2) shows, except for China (in spite of its slowing growth rate), Indonesia and Vietnam, this has been the case for five Asian countries. During the Great Recession of 2008–09 and again in 2011, Japan and Thailand in particular experienced troughs in growth rates. At the same time, India and Korea returned to relatively low growth figures, whereas Pakistan showed a slower recovery from the crisis than the other countries. In Asia, the damaging effects of volatile commodity prices, especially food and fuel, exacerbated by extreme weather conditions added to the effects of the worldwide slump in trade and investment, financial market turmoil and economic uncertainty. Though the Asian economies bounced back strongly after natural disasters such as the 2004 tsunami, economic insecurity and vulnerability have remained widespread, not least due to the lack of comprehensive social protection systems. In three countries, India, Indonesia and Pakistan, public social security and health expenditures were recently below 3 per cent of GDP (ADB 2013; UNESCAP 2013; ILO 2014b).

Figure 1.1 Development of GDP per capita (annual change in % in constant prices of local currency), eight Asian countries, 2001–13

Source: WDI (World Bank Development Indicators) database.

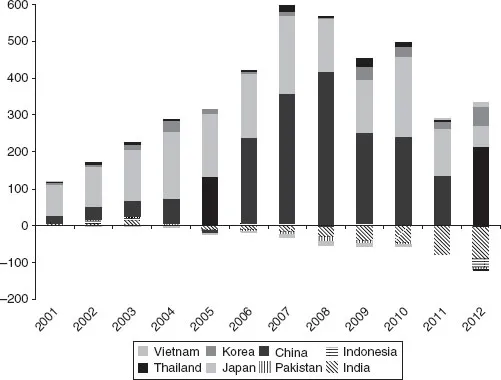

Large current account surpluses running since the 1997–98 Asian crisis have been an enduring economic feature for most of the Asian countries studied here. These surpluses in turn made up an integral part of the global current account imbalance. Figure 1.2 depicts the development of such surpluses. Though the external positions of India, Indonesia, Thailand and Pakistan had changed by 2012 and their current accounts showed deficits, the combined surpluses of the other four countries shown here were nearly three times as big. This was fuelled by the continual export-led growth strategies of China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Research of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) failed to find any evidence that their surpluses were rooted in underinvestment. By contrast, the researchers suggested that the key to rebalancing Asian growth towards domestic sources lay in promoting consumption rather than investment (Park and Shin 2009). This conclusion corresponds to arguments on the importance of domestic demand that we advance in this chapter.

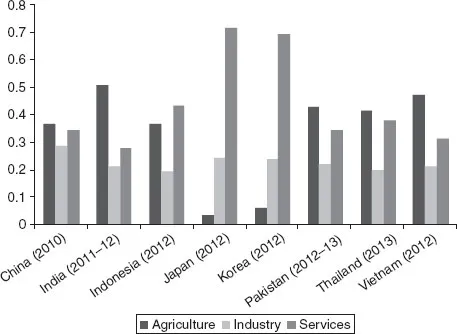

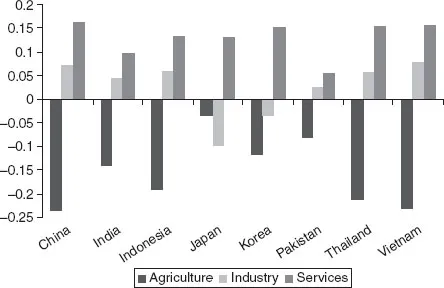

Figure 1.3, based on Table A.3A in the Statistical Appendix, depicts the employment structure of the eight Asian economies in 2010–13. Across these countries, major differences can be seen. Whereas agriculture in six countries recently accounted for one-third or more of total employment, in Japan and Korea its share has dwindled to 4 and 6 per cent, respectively. In these two countries, the service sector has become dominant with about seven in ten employed in services. Similarly, services have also developed into the largest sector in Indonesia, the only country of the eight where the employment share of industry has remained below one-fifth. China, with nearly 29 per cent employed in industry, leads here, followed by Japan and Korea at slightly over 24 per cent.

Figure 1.4 shows the shifts in national employment structures from 1990 until recently. The decreases in the shares of agriculture show up prominently. With 21–23 percentage points, the largest decreases were in China, Vietnam and Thailand, followed by Indonesia (19 percentage points) and India (14 percentage points). China and Vietnam, both with 7–8 percentage points increase, also showed the most rapid relative growth of industry. By contrast, in Japan and Korea the employment share of industry fell: by nearly 10 percentage points in Japan and by 3.5 percentage points in Korea. The other four countries saw the importance of industry in employment gradually growing.

Figure 1.2 Current account balances, eight Asian countries, 2001–12 (in billion US dollars)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook database.

In development economics, shifts between the sectors have been connected with demographic and labour market constraints, as shown in the dual labour model of W. Arthur Lewis (1954). In his model, productivity is driven by a modern industrial sector with the support of unlimited supplies of labour drawn from subsistence agriculture. However, a point will be reached when agriculture no longer delivers surplus labour at very low wage rates: the so-called Lewis Turning Point. Lewis’ assumption that economic growth would be led by sectors other than agriculture has proven to be correct. Between 1990 and 1999, in both EEs and LMIs the highest growth rates have been attained for manufacturing (excluding mining); during 2000–11 that continued to be the case in EEs, whereas in LMIs services took the lead. Worldwide observations over the past three decades show that GDP growth has been more consistently led by manufacturing growth than by the growth in other sectors (ILO 2014a, 23–31).

Figure 1.3 Shares of main sectors in total employment, eight Asian countries, the latest available year

Note: Agriculture also includes forestry and fishing; industry includes manufacturing, mining and quarrying, utilities (electricity, gas and water) and construction.

Source: Statistical Appendix, Table A.3A.

Figure 1.4 Changes in shares of main sectors in total employment (percentage points), eight Asian countries, 1990–the latest available year

Source: Statistical Appendix, Table A.3A.

As Chapter 2 on China explains, the Lewis Turning Point issue is highly relevant for that country. The point may well be less than a decade away whereby China’s surplus labour from agriculture disappears and a labour shortage emerges. This prospect could impact sharply on many aspects of China’s policies as well as on the world economy. It seems inevitable that China will seek to upgrade manufacturing industry and continue to make major efforts in innovation and education. At the same time, policies to decrease income inequality can be expected to boost domestic demand in China. Other Asian countries are facing similar challenges and may feel forced to pursue restructuring towards higher value-added activities, innovation and diversification, as chapters in this book testify. For instance, Chapter 4 questions the export-led strategy of Korea, as it is based on relatively low wages, minimal social security and a severely constrained trade union movement. Chapter 8 points to Indonesia’s vulnerability to world market competition from countries with lower wage levels and emphasizes the need to improve the country’s educational and transport infrastructure. Chapter 9 reports the debates on Thailand’s economic strategy and stresses the urgent need to modify its reliance on cheap exports and shift to higher value-added production while building a stronger domestic market.

Of course, the relevant actors, including trade unions and employers’ organizations, have to find national solutions for the economic, social and environmental challenges at stake. Nevertheless, there is some common ground. From the Asian country chapters, five preconditions can be isolated where progress is essential: (1) the effective recognition of the rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining (FACB); (2) the fixing of well-designed MWs; (3) the expansion of basic social security to the population as a whole and the appropriate funding for it; (4) improving both enrolment in and the quality of education, in particular secondary education and vocational training; and (5) the development of domestic markets catering for the growing purchasing power of the population. These five preconditions for improvement have been recognized by several international organizations (cf. ILO/IILS 2011, 2012, 2013; OECD 2011; ILO 2013, 2014a; UNDP 2014).

While cross-country econometric studies have shown that FACB rights along with industrial democracy are associated with higher (manufacturing) wages and considerable productivity gains (cf. Lee and Eyraud 2008, 49), five of the eight countries (China, India, Korea, Thailand and Vietnam) had not, by October 2014, ratified either the basic ILO (International Labour Organization) Conventions, No. 87 (Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise) or No. 98 (Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining) (ILO NORMLEX website). By contrast, the fixing of well-designed MWs has been boosted by some recent positive developments wherein Asian policy makers have pushed through relatively strong MW increases. The need to upgrade the economy and stimulate domestic demand appears to have been the driving force notably in China and Thailand.

1.2 Inequality and informality

This shift towards a more demand-led, ‘upgraded’ economy relies on the creation of positive interactions within and between social and educational policies, labour market governance and industrial relations. Such dynamics have become visible as developing countries have climbed higher up the income ladder (ILO 2014a, 47). Yet there is also widespread proof that they can be frustrated by high levels of income inequality that impede economic growth and employment creation (Van der Hoeven 2010; Ostry et al. 2014). High inequality may also jeopardize progress in improving health and education. For example, it has been found that in South Asia after 1990 worsening income inequality undermined large improvements in health and access to education (UNDP 2011, 28). It is widely recognized, moreover, that key sources of inequality in developing countries include the persistence of a large informal sector, urban–rural divides, gaps in access to education and barriers to employment and career progression for women (OECD 2011, 49).

Against the backdrop of international campaigns promoting decent work, we focus here on informal employment as a key factor. Indeed, according to recent ILO analyses (2014a, 39), there is a significant correlation between the incidence of informal employment and indicators of poor job quality. In informal work, different aspects of vulnerability are soon manifest (UNDP 2014, 9–10). However, it should be noted that across ‘our’ eight countries, the informal economy is quite heterogeneous. Beyond the classical two-sector dichotomy, multidimensional definitions of informality have emerged, focusing on workers’ entitlement to social security benefits and their employment status (Tijdens et al. 2015). In some countries, informal employment is (much) more widespread than the informal sector, and many informal workers can be found in formally registered enterprises. In countries with many workers de facto in informal employment, even MW systems with universal coverage may only protect a limited part of the workforce in matters of wage setting as is the case in Vietnam (Chapter 3). Hence, social protection is even more relevant here. We should add that in some countries a considerable inflow of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. Asia: A Comparative Perspective

- 2. China

- 3. Vietnam

- 4. Korea

- 5. Japan

- 6. Pakistan

- 7. India

- 8. Indonesia

- 9. Thailand

- 10. Europe: A Comparative Perspective

- 11. France

- 12. Italy

- 13. Germany

- 14. The Netherlands

- 15. The Nordic Countries

- 16. Central and Eastern Europe

- 17. The United Kingdom

- 18. The Russian Federation

- Statistical Appendix: Comparative Statistics

- Index