eBook - ePub

Energy Security and Sustainable Economic Growth in China

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Energy Security and Sustainable Economic Growth in China

About this book

This book focuses on various issues of energy, energy efficiency and environmental policy in China. It discusses different aspects on how China may maintain its fast economic growth through good management of energy consumption and development of various energy sources.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Energy Security and Sustainable Economic Growth in China by S. Yao, S. Yao,Kenneth A. Loparo,Maria Jesus Herrerias Talamantes, S. Yao, Maria Jesus Herrerias Talamantes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

International Comparison in the Energy Sector

Carlos Aller and Lorenzo Ductor

This chapter analyses the Chinese energy sector in comparison to other developing economies.

1 Introduction

Developing countries that are experiencing high economic growth have to face the subsequent environmental problems, exacerbated by the increase of their population and improved living standards. Kyoto Protocol (KP) did not bind developing economies (or the United States (US)) but the majority of them adopted the compromise of reducing carbon emissions in order to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) effects since then.1 Currently, developed economies emit sensibly more GHG emissions per capita than developing economies. However, the predictions about developing economies are not optimistic. It is expected that the emissions of counties that are not members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) will reach 28.9 billion metric tons in 2035, 73 per cent above the 2008 level (US Energy Information Administration (EIA), 2011).

Enkvist et al. (2007) estimate the costs of mitigation and abatement of GHG and conclude that developing economies have a greater potential of abatement at low cost for a number of reasons, like their large populations or the lower cost of mitigating new growth as opposed to reducing existing emissions.

Traditionally, developing economies have been reluctant to commit to reducing emissions as it can be observed in the successive United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) where those emerging economies have shown their fear of emission restrictions on the basis that they will curtail economic activity. The eighteenth session of the Conference of the Parties (COP18) at Doha (Qatar) on December 2012, ended with approval of an extension of the KP from 2013 to 2020 rather than a new one. Furthermore, a number of countries (Japan, Russia, Canada and New Zealand) have refused to sign the protocol again and there are no additional “committed” members.

Economic growth and its influence on the environment has been an object of study by numerous researchers. The so-called “Environmental Kuznets Curve” (EKC) postulates an inverse U-path from pre-industrial to post-industrial economies that suggests increasing environmental damages at the early stages of economic development followed by improvements in subsequent rising levels in per capita income.

Such hypothesis has been tested in several studies for industrialized countries. For example, the studies by Canas et al. (2003), who examine the EKC for 16 developed economies in the second half of the 20th century, and Galeotti et al. (2006) who, for a similar period of time, find evidence for the hypothesis in OECD economies, but not for the rest.

Notwithstanding, the EKC hypothesis is not highly supported when it is tested in developing economies, as in the paper by Focacci (2005) who tests the hypothesis for China, Brazil and India, three big emerging economies. Narayan and Narayan (2010) perform estimations on 43 developing economies to conclude that the hypothesis holds only in 35 per cent of them, in which the three countries mentioned above are excluded. By regions, the hypothesis would only hold in the Middle East and South Asia.

These results reveal the necessity of a better understanding of the energy sectors of developing economies in order to make environmental policy recommendations, given the important asymmetry across those economies and with respect to the developed ones. In this chapter, we provide a detailed description of the energy sectors of a selected group of developing economies, each of very different characteristics in energy resources and volume, but with the common feature of having high Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates in the last decade. We put special emphasis on China and some other highly populated emerging economies like Brazil, Mexico, India or Russia. The objective is to provide a good understanding of the problems faced by these countries regarding energy supply and environmental issues in the short–medium term in order to search for the appropriate policies that Chinese authorities must follow to achieve sustainable economic growth in the forthcoming years.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the nexus between energy consumption and economic growth. Section 3 describes the characteristics of the energy sectors: energy dependency, consumption and Carbon Dioxide (CO2) emissions; and current energy policies. Section 4 provides an international outlook on expected energy consumption and CO2 emissions in forthcoming decades and section 5 concludes and suggests some recommendations for policy makers.

2 Energy use and economic growth

There is a general consensus that energy plays an important role in the production process. However, empirical results on the causal relationship between energy and growth have yielded mixed results. For example, in a survey of the electricity consumption-growth literature, Payne (2010b) finds that for the 74 countries studied, 31.15 per cent supports the neutrality hypothesis, that is the absence of Granger causality between electricity consumption and economic growth. In 27.87 per cent of the countries studied, a unidirectional Granger causality from economic growth to electricity consumption is found. A unidirectional Granger causality from electricity consumption and economic growth is also found in 22.95 per cent of the surveyed countries. Therefore, for 60 per cent of the countries surveyed, the studies did not find a causal relationship from electricity consumption to economic growth. This suggests that conservation policies to reduce or constraint the consumption of electricity would not have an impact on economic growth for at least 60 per cent of the countries surveyed (Payne, 2010b).

The mixed empirical evidence is also found in China (Yuan et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2007 and Shiu and Lam 2004). Most of these studies use a small sample (30–40 observations) and implement a bivariate error correction model (energy consumption and GDP), which can lead to spurious correlations and erroneous conclusions through omitted variables and small sample problems. In this section, we do not focus on the causal relationship between energy consumption and economic growth. We instead present a descriptive analysis of the current and past situation of the Chinese energy sector relative to the main developing economies.

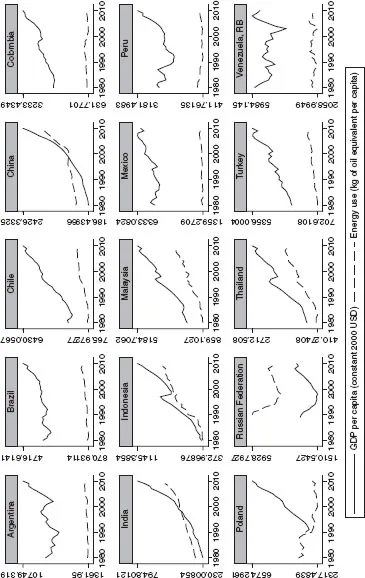

We start our analysis by comparing the GDP per capita (constant 2000 US$) and the Energy use per capita (kg of oil equivalent per capita) of China with respect to the main developing economies: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Poland, Russian Federation, Thailand, Turkey and Venezuela. We select these economies because the composition of their energy sector is very different but they share positive economic growth during the last decades.

China shows more rapid growth in real GDP than in energy consumption. Its real GDP per capita grew on average, by about 8.19 per cent between 1980 and 1989, while energy use per capita grew by 1.6 per cent during the same decade. Between 2000 and 2009, real GDP continued to grow, on average, by 8.70 per cent, while energy use grew by about 7.05 per cent. We observe the same pattern in most of the developing economies, although the GDP per capita growth in China was significantly much higher than in the other developing countries during the whole period, between 1980 and 2010.

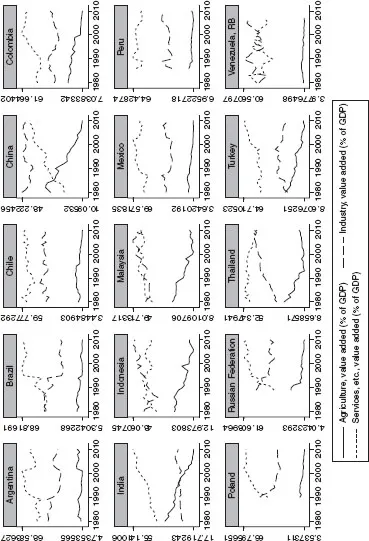

The gap between the GDP per capita growth and the energy use per capita growth in the South American developing economies is higher than in the non-OECD Asian economies. This may be a consequence of the different structure of their economies. Figure 1.2 shows the agriculture, industrial and service value added as a percentage of the GDP.

The industry share of GDP has declined in most of the South American economies except Chile, where the industry share is almost flat during the whole period. The industry share in China has also remained flat during the period and it represents around 50 per cent of GDP, the agriculture share has significantly decreased, while the service sector is becoming more and more important in the Chinese economy. Industry production is the most important sector in the developing Asian countries, which is more intensive in energy than services, the main sector in the South American economies. For example, manufacture-production represents 32 per cent of the Chinese GDP and 34 per cent of Thailand’s GDP while it only represents 12 per cent of Chile’s GDP or 21 per cent of the Argentina’s GDP, Argentina being the South American economy with the highest industry share. China has the considerable advantage of being able to produce many manufacturing goods because of its low cost of labour. This has facilitated a relocation of manufacturing production to China and other Asian economies leading to a significant increase in energy demand and consequently in CO2 emissions. We suggest that the Chinese government should tax its chemical and manufacturing production to internalize the costs of the damage caused by production, burning of fossil fuels and water pollution by those industries, which costs are now paid by all the inhabitants of China.

In the next section, we analyse the energy sector of these economies and their linkages with the GDP composition described above.

Figure 1.1 Energy use and GDP (per capita)

Source: The World Bank Data, 2012.

Figure 1.2 Sectors value added as a percentage of GDP

Source: The World Bank Data, 2012.

3 Energy sector characteristics

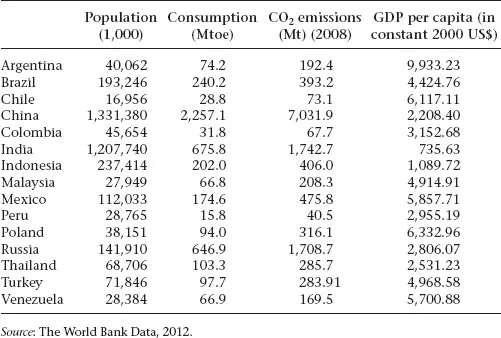

This section describes the energy sectors of the countries considered in this study. We first state in Table 1.1 some indicators of the size, the volume of energy consumption and CO2 emissions and the degree of development of each country.

China is the world’s most populous country: 22 per cent of total world population in 2009 resided in China. The consumption of energy and CO2 emissions has increased markedly over the last decades, not only in absolute but also in per capita terms. In other developing countries with high populations, like India and Indonesia, the consumption of energy and CO2 emissions is comparatively very low, which is partly explained in both cases by the relatively low percentage of people who have access to electricity (two-thirds against almost all the population for the rest of the countries). Furthermore, the Indian industrial sector is not as energy-intensive as the Chinese one, in which petrochemical and iron and steel production consumes more than half of the energy consumed by the industrial sector.

In the following sections we examine the degree of energy dependency, the consumption of energy disaggregated by energy source, and the volume of CO2 emissions across the different countries over the period 1980 to 2010.

Table 1.1 Population, energy consumption, CO2 emissions and GDP per capita, 2009

3.1 Energy dependency

Being a net energy importer or exporter economy is subject to different interpretations. On the one hand it can be said that a net importer economy is highly subject to external shocks. For example, the conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa in 2011 and 2012 shrunk the supply of crude oil, increasing the energy costs of many countries. On the other hand an alternative view is that in countries with scarce energy resources, energy independence is prohibitively costly and hence it is optimal for them to be a net importer.

For net energy exporter countries, not all the implications are necessarily good. These countries usually have deficiencies in human rights and economic development, as well as environmental problems derived from their additional energy production to be sold to other economies. In the case of China, its recent (1993) shift to being a net energy importer economy becomes of great importanc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 International Comparison in the Energy Sector

- 2 The Chinese Energy-Intensive Growth Model and Its Impact on Commodity Markets

- 3 China’s Energy Diplomacy via the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

- 4 The Institutional Setting of China’s Energy Policy

- 5 Energy Security in China: An Analysis of Various Energy Sources

- 6 Oil and China

- 7 China’s Alternative Energy Sources

- 8 Regional Electricity Consumption and Economic Growth in China

- 9 Regional Energy Intensity and Productivity in China

- 10 Energy Intensity and Its Policy Implications in China

- 11 Globalization and Energy Consumption in the Yangtze River Delta

- 12 Institutional Barriers to China’s Renewable Energy Strategy

- 13 Demand Effects on CO2 Emissions in China: A Structural Decomposition Analysis (SDA)

- 14 Environmental Protection and Sustainability Strategies in China: Towards a Green Economy

- References

- Index