eBook - ePub

Food and the Literary Imagination

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Food and the Literary Imagination

About this book

Food and the Literary Imagination explores ways in which the food chain and anxieties about its corruption and disruption are represented in poetry, theatre and the novel. The book relates its findings to contemporary concerns about food security.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Food and the Literary Imagination by J. Archer,R. Marggraf Turley,H. Thomas,Kenneth A. Loparo,Richard Marggraf Turley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Food Matters

A revolution is not a dinner party.

Mao Zedong (Chairman Mao)1

Down the hatch

In the language of topology, the branch of mathematics concerned with shapes and surfaces, the form of a ring doughnut is called a torus. Topologically an animal is a torus, with the digestive tract forming the equivalent of the hole in the doughnut. In other words, the gastrointestinal system is technically outside the body (hence egestion rather than excretion is the correct term for the elimination of digesta). Food moves through the human gut at the rate of about 0.25 m h–1. The comedian Peter Cook considered it ‘very interesting’ that what we eat is therefore ‘never … really fresh’.2

Before the era of X-rays, CT scanners, safe invasive surgery and the like, examining faeces (and urine) was medically important since it represented just about the only way of finding out about the state of one’s innards. The digestive tract as a passageway, simultaneously within and outside the body, has always been a source of linguistic metaphor and imagery for the creative artist. The mouth in particular – a multifunctional apparatus if ever there were one – is far more than ‘the orifice in the head of a human or other vertebrate through which food is ingested and vocal sounds emitted’ (OED). It lends itself figuratively to a point of exit such as river mouth or the mouth of a tunnel, the mouthpiece of a musical instrument, the barrel of a firearm, the orifice leading into a chamber or vessel, such as a jug, furnace, cave, volcano, flower or vagina. The written, visual and performing arts abound with images of swallowing-up, from the Biblical Jonah and the Leviathan to Dante’s Inferno, Swift’s modest proposal, Goya’s horrific image of Satan devouring his son, Alice and the rabbit-hole that leads to Wonderland, the lover and bibliophile being force-fed a book in Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989), Thomas Harris’s Hannibal Lecter, Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man (2005) – a documentary about the death of Timothy Treadwell and his partner, who were eaten by one of the grizzly bears they lived among – and the pie served by Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus to his arch-enemy Tamora.3 The latter example, in which a mother unwittingly eats the flesh of her two sons, equates the mouth with the anus, the womb with the tomb:

Titus Why, there they are, both bakèd in this pie,

Whereof their mother daintily hath fed,

Eating the flesh that she herself hath bred.

(Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus [1592], 5.3.59–61)

Maggie Kilgour has shown that the Eucharist and anthropophagy (the act of eating human flesh, whether one’s own or another’s) and the opposition between outside and inside are pervasive metaphors in Western literary works.4 (The Eucharist as a type of anthropophagic foodstuff freighted with socio-political as well as religious meaning is something we’ll explore further in Chapter 3.) These connect with the mouth as an erogenous zone, the interrelationship of sexual and nutritional gratification, and various sado-masochistic and cannibalistic fetishes such as vorarephilia, in which an individual is sexually aroused by the thought of eating, being eaten or watching others eat.

The hungry voice

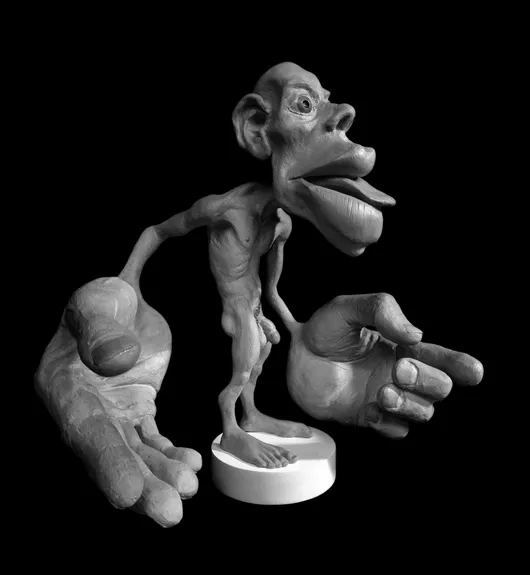

Skin keeps you in, but primarily keeps things out. (This has not stopped the cosmetics and health industries from ‘feeding’ skin with vitamins, DNA, collagen, arginine, antioxidants, peptides, seaweed extract, serum, herbal extract, essential oils and various milks.) However, in the few short millimetres between the skin of the face and the lining of the mouth, everything changes. Figure 1.1 shows the ‘sensory homunculus’, in which is represented the relative perception of the motor system as it is distributed around the human body. It shows that the mouth and tongue command a disproportionate amount of the brain’s attention.

Figure 1.1 Model of a sensory homunculus. Parts of the body are sized according to how much space the brain gives to processing sensory information about that part of the body

The evolution of the human vocal apparatus, with its rounded tongue and descended larynx, has made it difficult for the mouth to carry out more than one of its functions at a time.5 For reasons of physiology, and of social convention (‘don’t talk with your mouth full’), if you eat you can’t speak. Western history and literature are full of food disputes which serve as metaphors for vocal clashes and full-scale revolutions. Katniss Everdeen, the figurehead of rebellion against the repressive state, the Capitol, in Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games trilogy (2008–10), remarks: ‘It [the Capitol] must be very fragile, if a handful of berries can bring it down.’6 In fact, political and power systems have often been challenged by the decision to eat or not to eat. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) uses wheat to represent its aims, and all major world religions have used grass or grass products as metaphors (the Romans had their own personification of agricultural disease, Robigus). Grass is the first plant mentioned in the Old Testament. For the Abrahamic religions, human servitude began when Eve and Adam consumed the wrong type of fruit (the fruit of the tree from which they were forbidden to eat). The resulting ‘curse’ is described in agricultural terms. First, human reproduction is compromised. Secondly, as weeds are released from the earth, arable farming is itself transformed. This is God’s pronouncement (to Adam, it seems):

I will put enmitie betweene thee and the woman, and betweene thy seed and her seed: it shall bruise thy head … cursed is the ground for thy sake: in sorrow shalt thou eate of it all the dayes of thy life. Thornes also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee: and thou shalt eate the herbe of the field. In the sweate of thy face shalt thou eate bread, till thou returne vnto the ground. (Gen. 3: 15–19, KJV)

The next curse to fall on humankind, resulting in inequality within and between peoples together with the concept of racial differentiation, is figured as a choice between types of farming. God favours Abel’s gift of lamb over Cain’s sheaf of wheat (‘the herbe of the field’). The reason for God’s preference is, as with His ways more generally in the Old Testament, mysterious; the wording of the relevant passage in Genesis is obscure:

Abel was a keeper of sheep, but Cain was a tiller of the ground. And in the processe of time it came to passe, that Cain brought of the fruite of the ground, an offering vnto the LORD. And Abel, he also brought of the firstlings [firstborn] of his flocke, and of the fat thereof: and the LORD had respect vnto Abel, and to his offering. But vnto Cain, and to his offring he had not respect: and Cain was very wroth, and his countenance fell. (Gen. 4: 2–5, KJV)

For Cain, God’s meaning is quite clear: God prefers Abel because he prefers the food he produces. A choice between varieties of fruit (licit and illicit) has become a choice between methods of food production, and the outcome is the first murder and the second ‘fall’ of humankind (the so-called ‘curse’ of Cain). God, it seems, prefers pastoral over arable farming, and although both forms were, and continue to be, essential to human survival, the favouring of the former over the latter can also be perceived in the New Testament (as Colin Tudge observes, ‘it was the shepherds, successors of Abel, who attended the birth of Jesus. No one turned up with a sack of barley’).7 Daniel Quinn, in his philosophical novel Ishmael (1992), suggests that the story of Cain and Abel’s gifts perhaps mirrors the more widespread shift in emphasis between these two forms of farming in the Middle East ten millennia before the turn of the Common Era.8 Running concurrent with this Biblical narrative, the classical tradition opens with its own version of a food dispute: the Trojan War. The history of the Greek mainland in the first millennia BCE was overshadowed by its inability to feed itself. A battle for control of the Bosporus, and, with it, access to the rich grain-growing regions and forests of the Black Sea, the Trojan War of Homer’s account can be read as an allegory for a protracted and sprawling resource war. The beautiful Helen is thus a proxy for grain, pasture and wood – the things for which men would truly launch a thousand ships.9

The political history of food is as much about stifling vocal expression as it is about nutrition. Bread and circuses are supposed to keep the population distracted and placid. If they are restless because they have no bread, let them, in the words of ‘one highly placed observer’ (to use E. P. Thompson’s sardonic phrase), eat cake.10 ‘The murmuring poor,’ wrote the late eighteenth-century poet George Crabbe, ‘will not fast in peace.’11 Whereas a single, articulate voice of opposition can be argued with or shouted down, there is something disconcerting about a voice that is just audible but inchoate, and especially when that single voice becomes one of many. We will return to the threat posed by a particular group of ‘murmurers’ – the medieval religious reformers known as the Lollards – in Chapter 3.12

Food, then, is a gag (in at least two meanings of the word). The Abbot of Burton boasted that in thirteenth-century law, serfs possess ‘nothing but their own bellies’.13 When the voice of protest is liberated by dearth, it often aggregates to become a mobile chorus, the soundtrack to the particular form of direct action recognized as the food riot. E. P. Thompson’s seminal 1971 study of food riots starts with Proverbs 11: 26, which seems to play with God’s withholding of a certain type of fruit in Genesis 1: ‘Hee that withholdeth corne, the people shall curse him’ (KJV).14

Thompson takes issue with what he calls the ‘spasmodic view of popular history’, in which the common people ‘can scarcely be taken as historical agents before the French Revolution’.15 He argues that crowd action in eighteenth-century Britain is almost always driven by some ‘legitimizing notion’ and that the ‘food riot’ in this period was ‘a highly complex form of direct popular action, disciplined and with clear objectives’.16 There was a prevalent expectation as to what constituted legitimate practices in the food chain (‘the eighteenth-century bread-nexus’) and spasms of rioting represented reactions to offences against these conventions.17 Moral outrage, quite as much as deprivation, drove direct action. Long-standing tensions between the towns and countryside also helped fuel the canonical food riot, with urban populations suspecting those involved in the processing and distribution of grain and bread of dishonesty and extortion.18 (We will see this dynamic played out in Chapter 3’s analysis of Chaucer’s The Reeve’s Tale.)

‘Notoriously’, Thompson observes, ‘in years of dearth the farmers’ faces were wreathed in smiles’: the lower the yield, the more farmers might be expected to charge for their crops.19 He notes: ‘The September or October riot was often precipitated by the failure of prices to fall after a seemingly plentiful harvest,’ and quotes the early eighteenth-century poet Samuel Jackson Pratt:

Deep groan the waggons with their pond’rous loads

...

While the poor ploughman, when he leaves his bed,

Sees the huge barn as empty as his shed.20

The concept of the Just Price runs deep, and may be found in the works of theologians, such as St Thomas Aquinas, as well as in those of economists.21 It lies at the heart of the moral economy and when Just Price is debauched, social cohesion crumbles. Direct action against a corrupted, malfunctioning food chain thus represents a challenge to a corrupted, malfunctioning socio-political order, including any religion it might use to bolster its au...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Plates

- Acknowledgements

- About the Authors

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes on Literary Texts and Note on Usage

- Prologue: Food Security and the Literary Imagination

- 1 Food Matters

- 2 The Field in Time

- 3 Chaucer’s Pilgrims and a Medieval Game of Food

- 4 Remembering the Land in Shakespeare’s Plays

- 5 Keats’s Ode ‘To Autumn’: Touching the Stubble-Plains

- 6 The Mill in Time: George Eliot and the New Agronomy

- Epilogue: The Literary Imagination and the Future of Food

- Notes and References

- Select Bibliography of Secondary Sources

- Index