- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Responding to the targeted destruction of women, Fields argues for establishing Gender as a protected class under the Genocide Convention. Cases are explored, historically, anthropologically, psychologically and sociologically, from the author's field research, as well as focuses on morbidity, mortality and demographic documentation data.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Against Violence Against Women by R. Fields in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Critical Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Violence begins as a threat against identity and physical integrity, and escalates to dehumanization, making it possible for the perpetrator to rationalize the destruction of human life. The ultimate violence is genocide.

Violence against women, whether in the form of genital mutilation or honor killing, was never sanctioned or prescribed by any of the Abrahamic theologies. Those violent practices devolved from preAbrahamicic tribal practices in Africa and probably Eurasia.

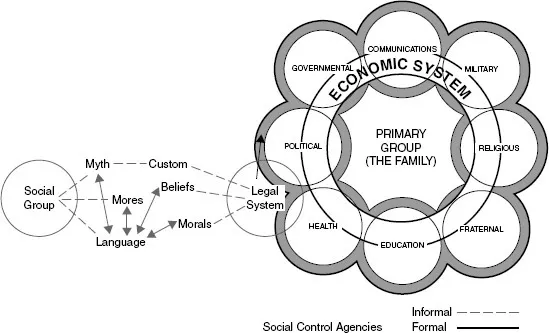

It is not a new phenomenon, but in the contemporary world, gender violence is practiced under the guise of religious or cultural “law” and historical custom. In fact, much of Africa and Asia functioned under tribal law, which subsumed as “protection of women,” the assumption that women’s bodies are the encasement for family honor. This tribal or “customary” law is a direct outgrowth of a militaristic society that is patrilineal and patriarchic. There is only an eighth of a step from “Protection” to Control. And protection of women in this context is control as with other property. (See figure 1.1.)

Militarism is predicated in vendetta. Implicit in this ideology is revenge that extends to all members of the opposition or competitive group and is, according to Jean Piaget, the second stage of moral development. When this is the mass ideology and children are truncated at this level, transgenerational violence is inevitable.

Many societies that have, at one or another time, practiced female infanticide or other destruction of females at an earlier point in their prewritten history had been dominated by women. Misogyny in many instances would be referred to psycho diagnostically as a “reaction formation.” In other instances, it has apparently evolved from the primitive myths of the female as power over life and death, natural disasters, and reproduction.

Figure 1.1 Institutions in a society.

For example, the Ban Po culture of central China was a Neolithic civilization believed by some Chinese archeologists, to have been matriarchal that may have had their own language and extraordinarily symbolic architecture and practical arts. They are credited as the foremothers of the Han people, who eventually dominated a large swath of central China and extended their boundaries into neighboring kingdoms.

The aristocracy in China had a very different culture from commoners, and women in the Han Dynasty were highly educated, and often, because of widowhood and prolonged regencies, they dominated the political life of the dynasty.

The society was monogamous, but kings and emperors had many concubines, and employed eunuchs to guard them. It was not unknown for the eunuchs to engage in internecine physical combat and even wars to assert the dominance of one empress dowager over another.

At the same time, and through many dynasties, the common people were mostly farmers and strongly patriarchal. Although marital fidelity and filial submission were two pillars of societal values, men were allowed to engage in sexual activity outside of marriage, and if they could afford it, to bring a concubine into the family home where, however, she would be subject to the dominance of the primary wife. Choices of marital partners were commended by the parents of the bride and groom. Not all of these were arranged through matchmakers but each marriage was always a complex contract, and was enacted through a very complicated set of ceremonies.

Daughters-in-law that came into the husband’s abode also served their parents-in-law. If there were several sons, one remained in the family domicile, and all would work the family land together. Each son, however, would get a piece of the family land as his inheritance and each daughter, although not mandated by law, had her share as her dowry. Women often had remunerative work outside the home. They spun and wove cloth, and made clothing and ornamental objects.

Predictors of Women’s Status

In one of my earlier books, The Future of Women (1985), I listed eight geopolitical and social conditions that are predictive of women’s status. I had derived these principles from extensive historical research and studies of the reports and proposals submitted to the United Nations Decade for Women. I think these predictors are useful in some instances in revealing where gender genocide will occur, including each of the cases discussed in this volume. They are:

1.Women’s position is always directly related to the society’s social and political conditions. Unrest, disorder, or distress in a society, will especially adversely affect women.

2.The status of women is a function of that society’s definition of marriage and family, which are defined by childbearing/rearing practices

3.There is no firm evidence that women as a class have ever enjoyed all the prerogatives of power equally with men. Certainly, individual women have been accorded power, but only on the understanding that they behave like “one of the boys.”

4.In most countries, rape, kidnapping, and enslavement have been used to control and terrorize women.

5.The denigration of women, like the denigration of a racial minority, provides an excuse and rationale for their economic exploitation. Assigning women to an inferior position in the workforce, for example, makes it is possible to get more work for less pay, thereby preventing the full employment of all workers, including men.

6.The subordination of women is worse within groups that are themselves oppressed. In such instances men are put in subordinate positions in relationship to other men, which slights his masculinity, and he seeks to restore it through sexual domination of women in his group.

7.The more a society is vulnerable to the whims of the natural environment, the more it is oppressed by mystical taboos, which tend to polarize the roles of men and women and regulate relationships between them.

8.The status of women is adversely affected by wars and violence. These glorify the stereotypical qualities of masculinity, but further restrict women to the role of breeder and feeder, because of the threat to the survival of the group. Furthermore, wars and violence require a psychological dehumanizing of the enemy and, in particular, of the women of the enemy society. (Fields 1985b)

Long before scientists recognized how monochrondrial DNA is uniquely important in tracing ancestry through matrilineal origins, Jews had traced the origins of individuals through their mothers, although they identified their caste lineage through their fathers. In the early polygamous societies, offspring took their identity as much from their mother as their father. If the father was high status, the status of the mother determined the offspring’s position. This remains the case in Pashtun and Bedouin societies today.

What inspired the diminution of women’s status and credibility in decision making is unclear. Certainly ancient pre-Judeo-Christian symbolism is replete with earth-mother and goddess images, both believed to celebrate fertility, the essential value for human continuity. Yet, in nearly every religion, goddesses also are associated with death as with birth. Several hundred years ago the professional who facilitated childbirth was the same person who assisted the dying. She came to be called the Midwife.

The Pieta, the image of the mourning mother cradling the dead son she brought into the world, reflects this duality in Christianity. In his book, The Mary Myth (1973), Andrew Greeley argues that Christian veneration of Mary is a way to incorporate the quintessential femaleness in the God idea. Mary elevates women from the pagan idol.

Before Christianity the Israelites took particular care to distinguish between their women and the pagan women surrounding them. Among the many stories illustrating this are those of Samson and Delilah and of Abraham and Sarah, who are clearly intended, in part, to illustrate the sharp divide between Israelites and the other peoples of their time and geography (Fields 1972).

Abraham, for instance, falsely described his wife Sarah as his sister when they tarried in Egypt as guests of the Pharaoh, so that he would not have to share her with or give her to the ruler. As was the custom, he received one of the Pharaoh’s concubines, Hagar, as a handmaiden. On the opposite end of this spectrum, is the woman Delilah, who was used by her brothers and tribe to seduce Samson, and lure him to disclose the secret of his strength while she drugged him so that his hair could be cut off.

The ancient Greek goddess, Hera, was celebrated as wife and mother but was also destructive, even killing her own son. The ancient Greeks somewhat mitigated this conflicted omnipotence of the female by way of the myth of the warrior females, Amazon. The word literally meant “without breasts” because they supposedly cut off their right breasts, to facilitate notching and drawing an arrow in a bow.

While there is no indication any such society existed, the idea of an all-female society in which men were used for sexual gratification, and where male infants were killed at birth, was perpetuated in other times and cultures with certain consistent features. Gaelic mythology presented the Danum, who were skilled practitioners of the martial arts residing in Alba (Scotland). They were said to be the teachers of the great warrior hero of Ulster, Cuchulain (Fields 1973).

Herodotus related that the demise of the Amazons came about because the women yielded to the Scythians, with whom they preferred sex to victory.

The Athenian lawmaker Solon institutionalized for the Greeks, and later for the Romans, the dichotomy of sexuality, in which sexually restrained women were seen as respectable whereas sexually active women were whores. Solon’s legislation, which minutely regulated Athenian life, was intended to block women from arousing conflict between men.

Yet another embodiment of the contradictions ascribed to women is Kali, the Hindu goddess of death, who is also the earth goddess and the goddess of light.

The profound enigma of life’s beginning and end is inextricably imbued with the mystery of female cyclic bleeding and pregnancy. Ignorance and powerlessness beget the divergent roles of women as goddess and witch, saint and seductress (Fields 1985b).

Ancient religions, such as that of the Israelites, for instance, identified the moon as female and as representative of procreation. The new moon represents the monthly renewal of women and is usually a cause for differentiation in rituals and other behaviors. In fact, to this day, Jewish tradition (which is quite different from ancient Israelite practices in many respects) includes special prayers on Rosh Hodesh, the new moon, which honors women.

The First “Pharaoh”

Among the Egyptians, the Israelites’ neighbors and sometime adversaries, was a well-documented example of the conflicting images and roles of women. There was no question but that males dominated the pharaonic dynasties, although a woman could be a regent if the descent fell on a very young male child, as happened with Tutankhamen. Still, the daughter of the great King Thutmose I, married by her father to a weak and sickly half-brother, had an extraordinary reign of more than 20 years. Hatshepsut, meaning “foremost of noble ladies,” ruled from 1508 to 1458 BCE as the fifth pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty of ancient Egypt. Egyptologists generally regard her as one of the most successful pharaohs, ruling longer than any other woman of an indigenous Egyptian Dynasty (Cleopatra was not born of an indigenous Egyptian Dynasty).

Although records of her reign are documented in ancient sources both numerous and diverse, early modern scholars diminished the importance of her contributions, describing Hatshepsut as a co-regent in power from about 1479 to 1458 BCE, during years 7–21 of a reign previously identified as that of Thutmose III.

Today, it is generally recognized that Hatshepsut assumed the full position of pharaoh and ruled 22 years. She outlived her half-brother/mate King Thutmose II and ascended the throne, discarding her female robes and assuming the crown and kilt of kingship. Initially this created some complications because all of the titles attributed to the high king were in the masculine. It is believed that her ascendancy gained her the title of Pharaoh, which was gender-neutral (Mertz 1964).

Hatshepsut was attributed a reign of 21 years and 9 months by the third century BCE historian, Manetho, who had access to many records that now are lost. She and Thutmose II had four daughters before his early death. Thutmose II also had a son with a non-Egyptian slave that became Thutmose III, who was considered Hatshepsut’s nephew. She at first served as his regent, but actually took the throne over the course of 20 years that historians originally attributed to the reign of Thutmose III. He was not happy about this, we’re told, and plotted to overthrow her. But this came to naught, as she had secured the support of several viziers who had served her father, and with whom she maintained a politically astute alliance. Her death is known to have occurred in 1458 BCE, and her nephew successor was determined to destroy all evidence of her accomplishments and importance (Fields-Babineau, 2008).

Her peaceful reign saw the completion of great construction projects and of artistic and cultural developments. Depictions of her in her tomb show that she extended trade to places beyond the bounds of her predecessors, who are depicted, significantly, with maces in acts of war.

Religious myth had it that she was actually the child of Amman-Re, the sun god. It was believed that all kings were offspring of Amman-Re and the queen, royal wife of the king (Mertz 1...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Africa: Gender Genocide

- Chapter 3 The Negev Bedouin: A Contemporary Remnant of Ancient Tribal Society

- Chapter 4 Sanctioned Mass Atrocities: Women in Afghanistan

- Chapter 5 India: Goddesses, Prime Ministers, Femicide Victims

- Chapter 6 China: Contrast and Contradictions

- Chapter 7 Siberia: Golden Woman, X-Woman, and Empresses to Anomie

- Chapter 8 Celtic Europe: Slaves of Slaves or Queens and Warriors

- Chapter 9 Epilogue

- Appendix: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Depression

- Bibliography

- Index