- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Craft and the Creative Economy

About this book

Craft and the Creative Economy examines the place of craft and making in the contemporary cultural economy, with a distinctive focus on the ways in which this creative sector is growing exponentially as a result of online shopfronts and home-based micro-enterprise, 'mumpreneurialism' and downshifting, and renewed demand for the handmade.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Craft and the Creative Economy by S. Luckman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Craft Revival: The Post-Etsy Handmade Economy

Craft, the handmade and making are currently everywhere. As Jakob has observed, ‘No longer a sequestered and quaint domestic leisure activity, crafts and DIY ... have redefined their images and social stigmas with progressive agendas of emancipation, individualization, sub-cultural identification and anti-commercialism as well as emerged as a multibillion-dollar industry’ (2013, p. 127). That is, ‘Crafts are currently being rediscovered not only as a hobby but also as a desirable enterprise’ (Jakob 2013, p. 127). For this reason I begin this chapter, perhaps a little counter-intuitively, with a different kind of ‘craft’: the making and selling of alcohol. Though prima facie this may appear a strange starting point from which to begin our journey into the contemporary craft economy, given the last few years have also witnessed an explosion of craft micro-brewing around the industrialised world, in many ways it is inevitable that these paths cross. Within the space of a single week I came across two separate instances where yarn-based craft was employed to market alcohol. The first was the unlikely sight of a crocheted label on a draught cider tap for Matilda Bay’s Dirty Granny Matured Apple Cider behind the bar at a local pub.1 Photographs of similar crochet labelling feature on other aspects of this product packaging such as bottles and boxes. In many ways this is a ‘jumped the shark’ moment for the contemporary craft renaissance. This phrase was coined following a moment in the television show Happy Days when the writers, seemingly out of fresh ideas after years of syndication, contrived an episode where the lead character Fonzie jumped over a shark on water skis. In television circles the phrase represents the moment a show loses credibility but it is now used more widely to denote the moment a cultural phenomenon passes its peak of popularity and quality and starts a rapid decline (Gleick 2011), often as a result of oversaturation (think the current zeitgeist fashion in interior design for exposed light bulbs and the use of wooden pallets as low-fi furniture or building materials). A 2011 offering from the stable of international alcohol giant CUB (Carlton and United Breweries) who are responsible, among many other labels, for the Foster’s brand, we are not talking about a small independent artisanal product here, at least not as the market might understand it given this corporate affiliation. But the Matilda Bay cider is produced at the backyard-sounding ‘Garage Brewery’ and is explicitly presented by CUB as a ‘craft cider’ offering from its makers of ‘craft beers’. To denote this status, what better way to brand it than wrapped up in crochet squares, just like Gran used to make?

The same week I also chanced upon a pile of boxes as part of a promotional display for Yarnbomb Shiraz from the nearby McLaren Vale winegrowing region (see Figure 1.1). Interestingly here, in a convention that definitely resonates with the promotional practices of the craft economy, the product name receives almost equal billing with that of the vintner, that is, of the maker, Corrina Wright. Corrina is Winemaker and Managing Director of Oliver’s Taranga, a winery which like many others in the region remains a small family business, albeit one now over 170 years old. Like the Dirty Granny campaign, Yarnbomb Shiraz is an engagement in marketing. But unlike the former, Yarnbomb is connected with an actual person, and through her to her family and a story of making, especially in the short video that explains the name as part of the wine’s promotion.2 It is a story of socks ‘with attitude’, made with love by a grandmother as her art, being brought together with her granddaughter’s art of winemaking. Both these instances of a promotional deployment of traditional women’s craft are clearly functioning as marketing tools for alcohol products, and seek to mobilise similar zeitgeist connections, and by association also to mobilise the artisanal qualities of care, skill and difference. But from this point on their stories diverge, in part fuelled by the market they seek to appeal to (cider tending towards a younger market than shiraz), as well as the production processes that gave rise to them. Both these very different uses of fibre craft to market alcohol link back to grandmothers, albeit the wine links us directly back to actual people and a very personal story, as distinct from the perhaps more cynical and risqué deployment by the multinational alcohol distributor seeking to evoke a cheeky ‘down home’, small-scale artisanal feel for their cider product.

Craft’s desirability as a marketing hook is clear evidence of its renaissance not only as a desirable set of objects or products, but also, valuably, as making, as evidenced by the use of craft signifiers to denote ‘artisanal’. The attraction of making lies, by definition, at the heart of the international maker movement – in many ways the more male-dominated counterpoint to the current, more female-driven craft upsurge – which has been particularly energised by the productive possibilities of new digital making tools such as 3D printing. It is also evident on television screens around the global West on which, alongside the many cooking shows that have proliferated over the last decade, we are now also witnessing the parallel growth of shows with a making focus. Some explicitly follow tried and tested formulas derived from cooking, such as BBC2’s The Great British Sewing Bee3 in which each week contestants are presented with a number of time-limited creative challenges, the results of which are adjudicated by judges, a contestant being eliminated weekly until only one remains as the winner. We are also seeing new life injected into more traditional genres (including home and garden shows) and more established making personalities via shows such as Monty Don’s Real Craft (Channel 4)4 and pretty much anything featuring Kirstie Allsopp.5 In the United States Martha Stewart operates across multiple media forms (including TV, magazine publishing and brand lines in department stores). All these shows work to democratise craft, de-mystifying making as a process ‘anyone one can do’. While this is both laudable and powerful in and of itself, this accessibility and visibility accorded to amateur making has, as we shall see, particular ramifications for craft’s status as a serious creative practice. Within the contemporary craft economy this especially impacts upon those operating at the more professional levels of design craft or studio craft practice, for whom these debates are hardly new, but who now face new challenges around such things as copyright and pricing as the craft marketplace grows online.

Figure 1.1 Yarnbomb Shiraz label

Sorce: Image courtesy of Corrina Wright.

Defining craft

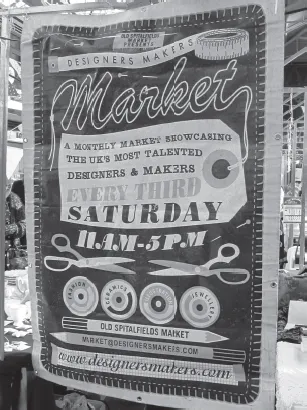

What the discussion immediately above also indicates is the complex terrain of terminology that circulates around craft practice at its many levels (from amateur through to fully professional), much of which is the direct legacy of a wish to locate one’s own particular standing in relation to traditional debates around the value and status of craft practice. The choice to identify oneself as a ‘designer maker’, or ‘design craft’, ‘studio-craft’, ‘art-craft’ practitioner is not an accidental one, with each choice indicating a desire to be identified with a particular aspect of ‘serious’ craft practice. It generally signifies a choice to be more closely aligned either to the commercial design industry or to the art world. Interestingly for this book, within the contemporary craft economy ‘design craft’ is frequently paired with ‘designer maker’, which in evoking ‘design’ represents not so much a desire to be aligned with industrial design per se, but operates within commercial craft spaces to signify the creative originality underpinning craft products for sale. That is, it operates as an affirmation of skill, originality and indeed effectively copyright; proudly craft, but resolutely not amateur. The design craft sector of the craft marketplace is especially, though not exclusively, highly visible in the emergence of curated design craft and, in the US, ‘indie craft’ fairs6 (see Figure 1.2 and also I.1, p. 3), and clearly resonates with current consumer demand for uniqueness and a sense of provenance in an age of seemingly faceless capitalism and mass production. The term ‘designer maker’ also potentially allows for scaling up when a business meets with success; like studio potters and other more traditional models, a designer maker can continue to be the intellectual property owner and creative face of a business, even while their designs may be handmade by hands not their own but under their supervision.

Moreover ‘craft’ itself remains in many ways a contested term within arts, crafts and design circles. The subordinate status often accorded to craft as compared with (visual) art is sustained, in part, by its ongoing connection to the past through a respect for techniques and the sustenance of traditional methods of making (including heritage crafts), as well as its links to a focus on materials as part of this respect for technique, and the connections between craft and manufacturing production. The latter is now playing out in interesting ways in the maker movement and in the emphasis on high-end design-led manufacturing as a potential answer to the movement of less skilled manufacturing offshore from the global West. The history and details of this rich nomenclature discussion are beyond the scope of this project which, located as it is in cultural studies, cannot even pretend to do justice to the topic as it has played out in other disciplines. Craft scholar Glenn Adamson (2007, 2013) discusses craft’s contested status, especially in relation to the generally more reified arts,7 at some length in his works. He identifies the schism between craft and art whereby the ‘craft world seems like a ghetto of technique, and the art world ... an arena of the free play of ideas shockingly divorced from knowledge about process and materials’ as a legacy the West inherited from the Renaissance (Adamson 2007, p. 71). However, he contends that the distinction between ‘art’ and ‘craft’ has for some time now been become increasingly blurred, for not only has craft practice learnt much from arts-aligned education and debates in the last half-century or so, but arts practice is increasingly employing ‘craft’ techniques:

Figure 1.2 Designers/Makers monthly market, Old Spitalfields Market, London

Sorce: image courtesy Designers/Makers Ltd.

as Museum of Modern Art design curator Paola Antonelli put it [in 1998, prompted by the work of Droog], ‘craftsmanship is no longer reactionary.’ Antonelli frames the shift in terms of problem-solving, arguing that designers’ interests in newly available materials on the one hand and found objects on the other motivated them to develop a craft-based practice. (Adamson 2007, p. 34)

Adamson observes that ‘craft’ can refer variously to a category, an object, an idea or a process (2007, p. 3). This book’s phenomenological focus upon the contemporary craft marketplace – its consumer and producer drivers, work practices, cultural aesthetics and practices – means each of these potential deployments of ‘craft’ will be in play.

The current resurgence in craft can be situated within a larger history of peaks and troughs in craft’s standing in the global West over the last hundred years or so. Like other cultural and economic practices with a strong reliance on consumer demand to generate high-profile waves of interest, there is a cyclical aspect to craft’s visibility. For while practitioners may consistently work away at their craft, historical moments in which craft practices are evoked in other fields mark particular upsurges in wider interest in crafted objects and making practices. In the global West we can thus identify the current moment as a ‘third wave’ of international interest in craft. The first wave was heralded by the late nineteenth-century emergence of the British Arts and Crafts Movement which gave rise to local manifestations around the English-speaking diaspora and also in the Nordic countries, strong players today in the contemporary design craft marketplace. The second wave of craft coincided with the heady countercultural hippie days of the 1960s and 1970s, which embraced crafts ‘more for their political, back-to-earth elements than their aesthetic’ qualities (Jakob 2013, p. 130). Each wave of interest in craft is indicative of wider social, cultural, industrial and economic trends, and the various transnational and local legacies that emerge out of each iteration have shaped what contemporary craft is today. In particular, the legacy of the debates around craft’s relationship to independent art, more commercially oriented design and/or traditional folk practice all continue to be played out, especially as we shall see in craft’s contested status as a creative industry. Indeed, there is contestation about the degree to which we can evoke the idea of ‘industry’ at all.

The shadow of the ‘first wave’ of crafting – the Arts and Crafts Movement – still looms large over the twentieth-century history and practice of crafts and design. This is true of the UK in particular, but it has also been influential in the United States and other English-speaking countries where its philosophies and aesthetics gained traction (Crawford 2005; Cumming and Kaplan 1991; Gauntlett 2011; Greensted 1993, 2005; Harrod 1999; MacCarthy 2009; Williams 1983), and elsewhere, for example in Finland where ‘national romanticism’ emerged in the early twentieth century as a local incarnation of this broader movement. Self-consciously the inheritor of the Romantic legacy, but much more politically engaged with the labour politics of its time, the Arts and Crafts Movement’s leading figures were motivated into opposition to the status quo by an intense antagonism to the division of labour brought into being by the work practices of the Industrial Revolution with its large factories and worker exploitation. The movement’s ideas had at their centre a focus on the importance of hand making, traditional materials and techniques, nature as inspiration and muse, as well as of meaningful labour as a necessary pillar of any civilised vision of employment. The traditional, pre-industrial creative labour of their day provided the paradigmatic model of what this looked like, and the movement’s leaders sought to extend it as a model throughout the whole of work. The emotional and pleasurable affordances of creativity and work underpinned this most Victorian of radical politics. While not all were card-carrying socialists, the thinking around the ideal organisation of working life and community inspired by the best practices of creative work paralleled Marx’s early opposition to ‘alienated labour’. As I have written elsewhere (Luckman 2012, 2013), it also has clear parallels with contemporary cultural work discussions regarding what exactly constitutes ‘good work’ (Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2011) in the precarious world of creative employment. However, the inspiration for the Arts and Crafts Movement’s vision of the good life was firmly historical; they were heavily influenced by medieval guild approaches and looked back to history for their own best practice models of cultural work. Thus, and like the Frankfurt School which followed it (Banks 2007, p. 31), the Arts and Crafts Movement celebrated of craft-based production systems.

In the face of rapid industrialisation, the Arts and Crafts Movement sought to rekindle the wealth of craft knowledge and, alongside it, they fought against the reduction of labour to production-line or routinised piecework joylessly undertaken by poverty-stricken workers. But the Arts and Crafts Movement was, clearly, uniquely focused on not only a political but also an aesthetic project. Indeed, it is via the iconic prints, objects and home furnishings of Morris & Co. and Liberty that contemporary consumers tend to be most familiar with the aesthetics of the movement. William Morris, entrepreneur, artist and revolutionary socialist, was ironically the great populariser of aesthetic consumption among the ‘chattering classes’, who sought ‘to modify and disrupt things, in the here and now by inserting finely produced material objects, and ethical working practices, into a society accustomed to “shoddy” products and exploitative factories’ (Gauntlett 2011, p. 37). A collaboration among friends largely drawn from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his first enterprise – Morris, Marshall, Fa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction Craft and the Contemporary Cultural Economy: The Renaissance of the Handmade

- 1 Craft Revival: The Post-Etsy Handmade Economy

- 2 Crafts as Creative Industry

- 3 Material Authenticity and the Renaissance of the Handmade: The Aura of the Analogue (or The Enchantment of Making)

- 4 Craft Micro-Enterprise, Gender and WorkLife Relationships

- 5 Self-Making and Marketing the Crafty Self

- 6 Craft Work and The Good Life: Creative Economic Possibilities

- Conclusion Craft Micro-Economies: More Than Cool Capitalism

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography