eBook - ePub

Football and the FA Women's Super League

Structure, Governance and Impact

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Women's football is the fastest growing participation sport in the UK. This book critically explores women's elite football from a sociological perspective, analysing the growth, governance and impact of the FA Women's Super League from its inception onwards.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Football and the FA Women's Super League by C. Dunn,J. Welford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The FAWSL’s Context within the History of Women’s Football

Abstract: This chapter gives a succinct overview of the development of the sport and the academic attention offered to women’s football to the present date, highlighting how this has contributed to knowledge of and current debates surrounding the sport. It includes work on not just the UK context but what has been learnt from the development of women’s football in Europe and North America. It provides a backdrop for our argument that an examination of the FAWSL can contribute to, extend and develop findings of previous research.

Dunn, Carrie and Joanna Welford. Football and the FA Women’s Super League: Structure, Governance and Impact. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137480323.0006.

Introduction

‘The future is feminine’, declared Sepp Blatter, the General Secretary of the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), in 1995 following a successful Women’s World Cup in Sweden (cited in Williams, 2004: 114). It was also a time of optimism for women’s football in the UK. The national governing body, the Football Association (FA), had recently taken over the organisational side of the women’s game, bringing it under the umbrella of the male model of football governance and establishing a Women’s Football Committee. Although few would agree with the current president of the world football governing body that the future of such a traditionally male sport was even verging on the feminine, there was perhaps at least a hint of optimism in the air. Women had fought long and hard to be given the opportunity not just to play football but also to be taken seriously as competitors, and the 1993 FA takeover was the signal from above that the game had been waiting for. In 2011, the FA launched the Women’s Super League (WSL), the first semi-professional football league for women, marking the beginning of a new era for the sport.

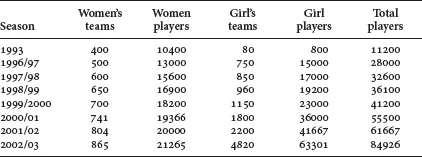

The current state of women’s football must, however, be understood as a product of the context in which it has developed. Football for women did not start with the FA takeover in 1993. Prior to this, the Women’s Football Association (WFA) independently ran the sport for 24 years, and before that, more informal structures extend back to the late nineteenth century (Williams, 2007). The well-publicised recent growth in female participation in football as promoted by the FA since 1993 (see Table 1.1) tends to overshadow the formal and informal policies and practices that have excluded women from football, and encourages the perception that women’s involvement in the sport is a recent phenomenon – there is no central archive for women’s football records (Williams, 2003). This not only demonstrates a lack of awareness of the challenges women have attempted to make to the male dominance of the sport but also denies women history and renders them invisible in the development of what is often termed England’s ‘National Game’.1 Such is the lack of acknowledgement given to the role of women in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century football, Tim Tate’s (2013) examination of female football players in this period of history is aptly subtitled ‘The Secret History of Women’s Football’.

TABLE 1.1 Registered female football players and teams, 1993–2003

In an attempt to reposition women within the history of football, and provide a context within which to understand the current position of women in the sport, a number of writers have provided an insight into the development of women’s football from both a structural and individual perspective (Lopez, 1997; Melling, 1999; Newsham, 1997; Tate, 2013; Williams, 2003, 2004, 2007; Williams & Woodhouse, 1991; Williamson, 1991), giving the sport a historical identity. An in-depth historical assessment of the development of the sport is beyond the scope of this book – and has been covered excellently elsewhere, particularly by the authors above – but an understanding of how this has shaped the identity of football for women provides a valuable lens through which to view the current state of the game. Behind all the gloss of the first semi-professional women’s football league in England lies a historically turbulent relationship between women who wish to play football and the male-dominated authorities that govern the game.

Historical development

The movement of women into the ‘time honoured male preserve’ of football (Williamson, 1991: 72) has traditionally been resisted in the majority of football nations, and with particular strength in the UK. In 1894, a British Ladies Football Club was founded, and a crowd of around 7,000 is reported to have attended their first match under FA rules in 1895; to put this in context, the previous season’s (men’s) FA Cup Final and Amateur Cup final drew crowds of 37,000 and 3,500 respectively (Williams, 2007). It is thought that the FA took a rather ambivalent attitude to the very early involvement of women in football, which Jean Williams (2007) considers reflective of their apparent predicament: the FA did not want to oversee the women’s game, but neither did they wish to allow it to continue outside of their governance. However, women first began playing football in large numbers around 20 years later during the First World War. Matches were played in front of thousands of paying spectators to raise money for war charities.

At a time where women found structural and ideological space within football, coupled with social and political progress made by women in the absence of men, the sport grew. Women proved that they could function perfectly well within the spheres that traditional stereotypes had denied them (Melling, 1999). At the same time, the charity focus allowed their participation to be perceived as evidence of patriotism rather than moral decadence (Pfister et al., 2002). Importantly, due to the suspension of male football, women were not competing with the established male game for the football audience – they were not perceived as serious footballers, and therefore did not pose a direct threat to the masculine hegemony of the sport (Williams & Woodhouse, 1991). Further, there was no attempt to replicate the structure of the male football league competitions, as games were organised in different areas of the country in response to fund-raising demand and economic potential (Williams, 2007). This cultural and structural separation from men’s football seemed to create a space for women’s football to flourish.

At the peak of its popularity, 53,000 people watched Dick, Kerr Ladies – inarguably the most successful women’s team in the history of the sport (see Newsham, 1997) – beat St Helens at Goodison Park, the home of Everton FC, on Boxing Day 1920. However, in the years shortly following the end of WWI, ‘normalisation’ returned to both male football leagues and the sexual division of labour. By 1921, the charitable nature of women’s football had begun to lose its legitimacy, leading to press calls for a return to normality in the gender order (Pfister et al., 2002). On 5 December 1921, the FA passed a unanimous resolution stating their opinion on the unsuitability of football for women, and ruling that clubs forbid women from playing on their grounds.2

Media reports at the time supported the ban, believing it to be reflective of the general sports-watching public who felt that football was not a sport for women (see Williams, 2007 for examples). There is little doubt that the football authorities saw the rise of women’s football as a threat to the male game (Giulianotti, 1999). The ban highlighted a resistance to women’s involvement within the structures of male football that has persistently impacted the development of the sport and remains a significant issue today: the struggles over legitimacy and equality that female footballers faced in 1921 have not been completely eradicated.

Women wishing to play football in other European countries faced similar struggles after the war. Charity matches between men and women in Sweden had just started to grow into more organised regular female matches when the 1921 FA ban in England was implemented. The Swedish media used this to support the feeling amongst ‘male football experts’ that ‘football is no sport for ladies’ (Hjelm & Olofsson, 2004). In France, women’s football matches had grown in popularity by the 1920s, but saw a similar decline follow. Although there was no official ban on women playing, interest was so low by 1932 that the French governing body stopped organising the women’s championship (Senaux, 2011). Warnings from doctors about the impact football might have on the female body coupled with a lack of grounds to play on contributed to this decline (Prudhomme-Poncet, 2007). In Germany, a country that would come to dominate European women’s football, the first recorded women’s team was forced to close in 1931 only a year after forming due to public outcry (Pfister, 2004). So England was not alone in cutting short any momentum women’s football might have gained in the early nineteenth century, but as will be discussed, was long behind other countries when it came to addressing this exclusion.

There is historical evidence that teams continued to play several years following the 1921 ban, even in front of sizeable crowds, and Dick, Kerr Ladies toured the USA in 1922 where women had begun to play football in colleges (Williams, 2007). But the longer-term implications of the ban were disastrous for women’s football. Without permission to play in existing grounds, crowds were limited and the spectacle lost. The sport was socially, culturally and economically marginalised (Williams, 2004), and without official recognition and support, the public’s interest, trust and credibility also disappeared (Williamson, 1991): the period of popularity was over. The development of football as a male preserve was protected, strengthening discourses of female unsuitability for physical contact sports.

Despite this exclusion and separation, women’s football continued independently. A total of 48 member clubs formed the Women’s Football Association (WFA) in 1969. Women’s football remained very much a participatory activity rather than a spectator sport (Williams, 2006); a distinction which remained throughout its growth and arguably still lingers today. The WFA had no official sanction from the male governing body; although the FA altered the constitution allowing ladies’ teams permission to apply for affiliation, the WFA found their requests for formal links with the FA rejected in 1971, 50 years after the original ban (Williams, 2007). Although UEFA affiliates had voted that very same year to recommend all member states to take control of women’s football under their respective governing bodies, the English FA continued to resist this. FIFA were similarly reluctant to relax their regulations; Williams (2007) details correspondence between the WFA and the FA concerning a Women’s World Cup proposal, to be hosted by England and supported by (male) World Cup winners including Bobby Moore, in which the FA merely reiterated FIFA’s stance on sanctioning competitions for non-affiliate members: it would not happen. Ten years later, the 1981 FIFA technical meeting discussed the development of women’s football in member states; despite reiterating its lack of desire to sanction a Women’s World Cup, members did agree that the women’s game should come under the jurisdiction of governing bodies – although this should be kept separate to women’s football in case they should benefit from (male) coaching and training facilities (cited in Williams, 2007: 144).

So 80 years after the FA banned women from using football grounds, and only 30 years before the FA launched the WSL, FIFA reiterated the fear that women might benefit from the use of facilities clearly (and bizarrely) intended for the sole use of male players. The WFA continued to grow, although tensions over the direction the women’s game should take were central throughout the history of the organisation with ideals of participation conflicting with a more competitive, professional approach (Williams and Woodhouse, 1991).

The FA takeover and beyond

In 1993, the FA formally took control of the administration of women’s football from the WFA. As a voluntary organisation, the WFA had encountered problems in attempting to accommodate the growth of the sport, with a weak infrastructure compounded by financial difficulties (Lopez, 1997). To highlight the relative timing of this takeover, women were accommodated in their respective governing bodies in Germany, Norway, Denmark and Sweden in the early 1970s, following the UEFA call for national football associations to take responsibility for the women’s game (Hjelm & Olofsson 2004; Fasting, 2004; Skille, 2008). Interestingly, the DFB (German Football Federation) accepted women’s football in 1970 but modified the structure with shorter matches, no studs to be worn and matches played in the summer months instead of the winter (Pfister, 2004). (The FAWSL is played in the summer, a format with several unintended consequences that will be discussed throughout the rest of this book. The DFB clearly thought a summer season was more appropriate for what was a ‘watered down’ version of men’s football.)

Post-1993, women’s football began to be brought in line with the established male structure. Leagues and cups were given FA titles, a Women’s Football Committee was established and the post of Women’s Football Co-ordinator created. The league pyramid became more streamlined to match more closely the existing male football league pyramid. The FA proposed a professional league for women that would be in place by 2003. Hope Powell was appointed as the first full-time women’s national football coach and 20 Centres of Excellence were set up throughout the country in 1998 to provide a pathway for talented girls. In the decade following the FA takeover, female participation figures in England, especially for girls, saw a rapid rise (Table 1.1) and in 2002 football overtook netball as the most popular sport for girls (Williams, 2013).

However, the majority of the changes that were made over the ten years following the FA takeover did little to alter the way female football was perceived – as an inferior version of real (male) football. There were serious concerns that women’s football was simply being ‘bolted on’ to existing male structures, with little structural change to reflect the needs of women and girls (Sue Lopez, evidence submitted to DCMS, 2006). The proposed professional league did not materialise, and the FA remained a male-dominated institution. A recurring pattern from the 1920s to the present day is the lack of female influence in the decision-making structures of football, which creates a conflict of interest between female participants and male administrators. Integration of women’s and men’s football has involved the acceptance of an institution that historically dismissed the sport and has been traditionally hostile (at best) to the involvement of women (Williams, 2003). The 1993 takeover had a minimal impact on the male-dominated nature of the FA or the way female football was perceived (Williams, 2004). Despite repeated recommendations that the FA reform at the top level to reflect the increasingly ‘diverse interests’, little has changed in this regard to the present day (DCMS, 2006, 2011, 2013).

Academic research since the 1993 takeover has provided a valuable critique of the impact that this had on the game. The FA has been criticised for its reluctant and limited acceptance of women into its organisational structures (Welford, 2008, 2011; Williams, 2003, 2004). Studies have demonstrated how although participation rates particularly amongst girls did indeed rise, they continued to face considerable opposition and a lack of both formal and informal opportunities (Griggs, 2004; Griggs & Biscomb, 2010; Jeanes & Kay, 2007; Harris, 2002; Skelton, 2000). Things were no better for adult recreational players who continued to negotiate the complex relationship between a traditionally male sport and constructions of femininity and sexuality (Caudwell, 1999, 2003, 2004; Harris, 2001, 2007; Scraton et al., 1999; Welford & Kay, 2007) and ethnicity (Scraton et al., 2005). The reported rise in football participation levels amongst girls and women, alongside the potential legitimacy given to women’s football by being administered and co-ordinated by the FA, was seemingly doing little to break down the barriers to integration that women have historically faced.

Twelve years after the FA had taken over the running of women’s football, the hosting of the European Women’s Championships in England in 2005 gave the game a timely boost in profile. The FA considered the tournament a huge success, with 29,092 watching England’s opening game against Finland (Bell and Blakey, 2010) and higher than expected audiences both in the stadium and for televised matches (Harlow, 2005). The Women’s Sport Foundation went so far as to describe the televising of England matches at Euro 2005 as a ‘real breakthrough’ (cited in DCMS, 2006). This was a significant boost to the profile of the game and suggested an appetite for women’s football amongst the public that might herald a new era of more equitable treatment of women’s football (Bell, 2012). England’s performance did not, however, match the anticipation and they finished disappointingly bottom of their group.

The on-field difficulties faced by the English national team at Euro 2005 were inargua...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 The FAWSLs Context within the History of Womens Footbal

- 2 The Launch of the FAWSL

- 3 The Expansion of the FAWSL

- 4 The FAWSL2 Controversy: Doncaster Belles and Lincoln Ladies

- 5 The Media Coverage of the FAWSL: A Girl Thing?

- 6 Public Reaction to the FAWSLL

- 7 The Future of the FAWSL

- References

- Index