eBook - ePub

Cybercrime Risks and Responses

Eastern and Western Perspectives

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cybercrime Risks and Responses

Eastern and Western Perspectives

About this book

This book examines the most recent and contentious issues in relation to cybercrime facing the world today, and how best to address them. The contributors show how Eastern and Western nations are responding to the challenges of cybercrime, and the latest trends and issues in cybercrime prevention and control.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cybercrime Risks and Responses by Russell G. Smith, Ray Cheung, Laurie Yiu-Chung Lau, Russell G. Smith,Ray Cheung,Laurie Yiu-Chung Lau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Ciberseguridad. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Cybercrime Risks and Responses – Eastern and Western Perspectives

Russell G. Smith, Ray Chak-Chung Cheung, and Laurie Yiu-Chung Lau

Crime has traditionally been a domestic concern for nation-states, with individual jurisdictions having their own responsibility for policing, prosecution, criminal trial, and the imposition of judicial punishments. Although some conventional crime types, such as maritime piracy, smuggling, and organized crime have always crossed jurisdictional borders and required transnational cooperation for investigation and judicial responses, it was not until the mid-twentieth century that crime became a more globalized phenomenon. As Findlay (1999, p. 2) observed:

The globalisation of capital from money to the electronic transfer of credit, of transactions of wealth from the exchange of property to info-technology, and the seemingly limitless expanse of immediate and instantaneous global markets, have enabled the transformation of crime beyond people, places and even identifiable crimes.

Findlay goes on to explain that “having said this, our world is still far from the universalised culture in all quarters” and that “globalisation is a transitional state” (1999, p. 2).

Since 1999, however, developments in information and communications technologies (ICT) have, arguably, facilitated the process of globalization markedly and created a world that, in many respects, crosses jurisdictional boundaries freely and without difficulty. Criminals have benefited greatly from developments in ICT in terms of facilitating communication, identifying potential victims of economic crimes, and obtaining information that can be used to facilitate crime. Criminals have also used ICT to counter the efforts of law enforcement to detect and respond to crime, such as through hacking into secure policing networks, encrypting information against law enforcement inspection, and laundering the proceeds of crime electronically.

One important question that organizations such as the United National Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has examined is how different regions of the world have experienced technology-enabled crime and responded to it through prevention and enforcement activities. The use of ICT by transnational and organized crime groups has created considerable concern internationally (Choo and Smith 2008), with the UNODC beginning to develop normative approaches to deal with the problem (UNODC 2013). In the Asia-Pacific region, attention has also been focused on these concerns, with a number of international conferences and events held to share information on how best to respond to the challenges that new technologies have created. Of particular relevance are the Asia Cyber Crime Summits held in Hong Kong in April 2001 and November 2003, whose proceedings were published by Broadhurst (2001) and Broadhurst and Grabosky (2005). More recently, Chang (2013) has examined cybercrime in the greater China region and reviewed various regulatory responses and crime-prevention initiatives in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

In August 2013, an international conference on cybercrime and computer forensics organized by the City University of Hong Kong and the Chinese University of Hong Kong was held in Hong Kong. Thirty speakers from ten countries across the region, as well as from North America and Europe, examined the most critical issues facing governments, business organizations, and consumers in relation to computer-enabled crime. From this group of policy and business experts, perspectives on cybercrime were obtained that could be said to reflect both Eastern and Western perspectives. A selection of papers presented at this conference form the chapters published in the current volume.

Clearly, many of the issues concerning computer crime victimization and the use of technology to respond to cybercrime are common across nations, be they in the East or in the West. Victimization experiences are, to a large extent, highly similar, whether they concern malware infections, consumer fraud, dissemination of illegal content, or facilitation of terrestrial crimes such as copyright infringement, theft, or stalking. An indication of some areas of difference in cybercrime victimization is apparent from the results of a survey undertaken by the UNODC (2013) in which the most common types of cybercrimes encountered by national police in four principal global regions were assessed. It was found that crimes involving child pornography were more prevalent in police investigations in Western than in Eastern regions, while unauthorized access to networks was more prevalent in Eastern than in Western regions. Computer-related acts involving racism and xenophobia were only considered to be prevalent in police investigations in Asia and Oceania (UNODC 2013, p. 26). Such differences, however, reflect the priorities of regional law enforcement agencies rather than the underlying incidence of different cybercrime types.

The present volume’s Eastern and Western perspectives derive more from the location of the authors of individual chapters than the content of any continental differences. Seven come from Greater China, five from Australia, three from Europe, and two from North America. It is apparent that most of the issues being discussed among cybercrime researchers today are common across national borders, with differences only being apparent in the incidence of some forms of cybercrime and the rate of implementation of specific response strategies. For example, the incidence of computer access-related crime appears to be more prevalent in China than in Western nations, while content offending, particularly involving child-exploitation material, is prosecuted more often in the West than in the East (Smith, Grabosky and Urbas 2004).

In relation to responses to cybercrime, there have been marked differences in the roll-out of technologies used to minimize risks. In the case of payment card fraud, Roland Moreno introduced smart cards in France in 1974, while the United States is just beginning to roll out chip-enabled credit cards in 2015, albeit without the use of PINs. Similarly, biometric user authentication systems have been implemented in some countries at a much earlier time than in other countries (see Chapter 2). Arguably, cloud computing will be taken on in all developed nations at much the same time – with all the benefits and risks that that might entail (see Chapter 10 by Alice Hutchings et al. below). These and other developments are examined in the following chapters by academic scholars, business professionals, and government policy-makers from both Eastern and Western countries. Their solutions to the problem, it will be seen, have much in common.

The present volume is organized in four parts. The first begins with an historical review of cybercrime globally and then examines two areas of cybercrime research that raise both methodological and ethical questions as well as substantive issues of access to, and analysis of, information posted online (Chapters 3 and 4). Part II examines six contemporary cybercrime risk topics affecting individuals, business, and government with contributors from both Eastern and Western countries (Chapters 5 to 10). Part III considers a range of industry, criminal justice policy, and forensic responses to cybercrime that have relevance to business and governments globally (Chapters 11 to 14). The final part presents three research-based studies that concern privacy and freedom in cyberspace, particularly in the realm of social media (Chapters 15 to 17). The chapters include current theory and information on cybercrime risks for the future and a wide range of policy and industry responses available to counter the growing threat to information and communications technology infrastructure. Unlike some other publications that have addressed the problem of cybercrime from a purely academic perspective, the present collection includes not only research from government policy analysts but also university-based researchers and theorists and representatives from industry who have agreed to share their perspectives on how some sectors, such as banking and financial services, have sought to address cybercrime risks in recent years.

Some of the principal issues and themes explored in the following chapters are as follows. At the outset, it is important to understand the rapid growth in ICT usage in the region. In their discussion in Chapter 16 of cyber-crowdsourcing, or what is known in China as “human flesh searching,” Lennon Chang and Andy Leung cite Internet World Statistics (2015) that there are more than 650 million Internet users in the Greater China Region, most of whom have a presence in online communities such as Golden (HK), HK Discuss (HK), U-wants (HK), PPT (Taiwan), Weibo (China), and Facebook (HK and Taiwan). China Internet Watch (2014) also reports that there were more than 167 million monthly active users on Weibo in 2013, while in Taiwan and Hong Kong, 70 percent of Internet users are on Facebook. Chang and Leung observe in Chapter 16 that these substantial numbers of “netizens” and platforms provide an excellent base for cyber-crowdsourcing activities in the Greater China region.

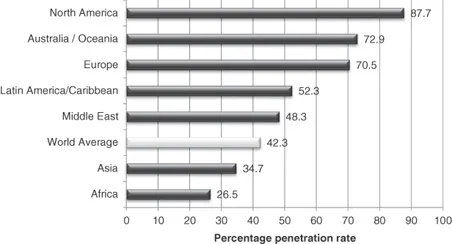

Of course, similarly high proportions of citizens in Western nations are also online. Internet penetration statistics that show the percentage of the population in various regions who are users of the Internet vary considerably, as shown in Figure 1.1. North America has the highest penetration rate of 87.7 percent of the population, while Asia has the second lowest rate of 34.7 percent. However, in terms of numbers of users, Asia has by far the largest number of Internet users of any region in the world, with 1,386 million users at 30 June 2014, or 45.7 percent of all the world’s Internet users (Miniwatts Marketing Group 2015, n.p.).

Figure 1.1 World Internet penetration rates by geographical region – Quarter 2, 2014

Miniwatts Marketing Group (2015, n.p), used with permission.

The relevance of these statistics lies in crime opportunity theory, explained by Russell Smith in Chapter 2. Opportunity theory seeks to explain trends in crime rates in terms of changes in the routine activities of everyday life. It is argued that changes in routine activity patterns influence crime rates by affecting the convergence in space and time of three minimal elements of direct-contact predatory violations: the presence of motivated offenders, the availability of suitable targets, and the absence of capable guardians against a violation. Having such a large proportion of the population using the Internet and other electronic devices creates a high-risk environment for crime, particularly in the presence of high financially driven motivations for offending and the difficulties that the Internet presents in terms of effective policing or guardianship. Although victims of cybercrime are located in both Eastern and Western countries, it can be expected that the future will see the highest incidence of victimization, in terms of numbers of victims, in Asia. In addition, such a high rate of ICT usage will inevitably mean that high numbers of individuals based in the Asian region may choose to engage in cybercrime perpetrated against not only their own citizens but individuals from all nations. Motivations for offending are likely to be great in countries with a low GDP but ready access to inexpensive technologies. As a result, the pressure on government and business to implement effective preventive strategies remains paramount and urgent.

The ever-expanding use of ICT in both the East and the West has created opportunities for criminality that were considered to be purely hypothetical over a decade ago. In Grabosky and Smith’s (1998) early review, Crime in the Digital Age, questions of cyberterrorism, organized cybercrime, misuse of social media, wireless and mobile technological risks, and cloud computing were not on the horizon, but they now occupy a prominent position in policy and industry discussion. Peter Grabosky, in Chapter 5, explores the question of whether organized cybercrime constitutes a national security threat, arguing that the answer depends on one’s definitions of “national security” and “organized cybercrime.” A response to this comes from Gregor Urbas, in Chapter 13, who presents a clear exposition of the highly technical laws that govern accessorial liability when applied to online organized crime. It is suggested that a more explicit recognition of “virtual presence” is required as the key legal element that could also assist in resolving persistent questions about identifying where a crime was committed.

One of the commonalities of cybercrime across nations is the financial motivations that underlie the vast majority of acts of illegality perpetrated online. Laurie Lau, in Chapter 6, provides a review of a selection of court cases involving Internet banking fraud in Hong Kong and demonstrates how the rule of law has helped Hong Kong achieve its position as an economic hub in Asia despite these online risks. Data from the Australian Cybercrime Pilot Observatory are presented in Chapter 7 to illustrate the important role that spam plays in enabling financial crime online. Alazab and Broadhurst explain some of the new methods of locating new victims of financial crime, such as right-to-left...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. Introduction: Cybercrime Risks and Responses – Eastern and Western Perspectives

- Part I: Understanding Cybercrime Through Research

- Part II: Contemporary Cybercrime Risks

- Part III: Industry, Criminal Justice, and Forensic Responses to Cybercrime

- Part IV: Privacy and Freedom Online

- Index