![]()

1

Introducing Citizen Participation in Health Systems

There is a broadly based consensus across the political spectrum that opportunities for citizen participation should be encouraged, as both an intrinsic ‘democratic’ good and a route to myriad benefits, from efficient public services to more cohesive communities. This is not new; writing in 1970s America, Pateman (1976, p. 1) said that the term had become so ubiquitous that ‘any precise, meaningful content has almost disappeared’. However, contemporary calls for participation differ, in important ways, from the radical demands of the 1960s and 70s. Polletta (2014, p. 457) argues that:

participatory institutions [of the 1960s] were seen as firmly outside the establishment. Today, they are the establishment. The arguments then for participation were principled. Today, they are practical … In an important sense, participatory democracy has gone mainstream.

This mainstream consensus on the need for, if not the means to, more participation permeates organisations in the public sector. Warren (2009a, 2009b) has argued that citizen participation initiatives are transforming the nature of contemporary democratic systems as the institutions of representative democracy struggle to retain their legitimacy, political parties drift away from their popular base, and electoral turnout falls. It is no longer seen as adequate, or even perhaps possible, for elected politicians to act as the sole conduit for public knowledge and action into the large organisations which administer and deliver public services. Across countries and in administrations across the political spectrum, these organisations have been mandated to develop, manage, and evaluate mechanisms of public participation.

This book takes an interpretive, critical approach to participation in health systems, an approach rooted in the work of scholars such as Wagenaar (2011), Yanow (2000, 1996) and Bevir and Rhodes (2006). It draws on research conducted in one specific (set of) institution(s), the National Health Service (NHS) in Scotland, where participation is often referred to gently as ‘public involvement’. Concerns about public accountability in the UK NHS can be traced back to its creation (Hunter and Harrison, 1997; Klein and Lewis, 1976). In the early days of the NHS Bevan famously declared: ‘The Minister of Health will be whipping-boy for the Health Service in Parliament. Every time a maid kicks over a bucket of slops in a ward an agonised wail will go through Whitehall’ (quoted in Foot, 2009, p. 195). Since the 1970s, health policy has been concerned to establish other avenues for public redress and influence than direct control by central government. However defining the means of participation has repeatedly proved problematic for policymakers: Klein (2010, p. 234) describes the reform of public involvement policy in the UK as a ‘stutteringly inconsistent process’. Proposed measures have included repeated reforms of local structures of public involvement, reforms of complaints systems, increasing local authority oversight of NHS services and, in Scotland, the direct election of members of Health Boards. However, as this chapter will demonstrate, the consistency of the criticisms and dilemmas which have plagued the various models of involvement over time is remarkable (Carlyle, 2013; Learmonth et al., 2009).

In exploring practices of participation within the Scottish NHS, this book probes fundamental tensions within current discourses of participation. These relate to the capacity of techniques of participation to generate adequate legitimacy, and to accommodate ‘small-p’ politics and conflict, which have a habit of spilling out of the participation initiatives that organisations plan. By filling a perceived political vacuum at the local level of the NHS (Klein and New, 1998), policies of participation have generated new political terrain, and this book is therefore simultaneously an examination of policy implementation, and of grassroots political action in both ‘invited’ and uninvited spaces (Gaventa, 2006). This introductory chapter reviews the current state of knowledge on citizen participation in healthcare, highlighting some of the challenges of research in the field, and then introduces the conceptual approach taken in this book.

Empirical studies of participation in health systems

Healthcare is one field where participation has been a major trend for decades (affirmed by the World Health Organization (1978) as ‘a right and a duty’ for citizens). However as Harrison and Mort (1998, p. 66) point out, the rhetorical ease with which participation is celebrated is not matched in practice. This is a field of academic study which has grown rapidly since the 1990s, and which is widely based across a range of health systems, with the vast majority of the literature from Europe and North America (Conklin et al., 2015). Empirical studies demonstrate a range of approaches to studying public involvement, with case studies of local initiatives (found to comprise 74% of the available literature by one systematic review (Crawford et al., 2002)) and surveys of multiple organisations the most popular approaches. However, it is a field which is increasingly acknowledged as problematic. While some studies celebrate ‘successful’ involvement (often, as Crawford et al. (2002) point out, in case reports authored by workers involved in projects), many others highlight difficulties and obstacles in participatory practice.

Three closely related systematic reviews of the area (Conklin et al., 2015; Crawford et al., 2002; Mockford et al., 2012) come to the same broad conclusions. Firstly, researchers have not generated adequate evidence on the outcomes of participation in healthcare (Conklin et al., 2015; Crawford et al., 2002; Mockford et al., 2012). Rather, a mass of often interesting case studies of implemented participatory activities document (with remarkable consistency) the process of participation. Secondly, and arguably intrinsically related to the first issue the reviews identify, studies of participation in healthcare proceed with minimal attention to the conceptual basis of the field (Conklin et al., 2015; Mockford et al., 2012). That is to say, research documents instances of practices which policymakers, practitioners, or participants consider to be ‘participation’, without relating this practice to a clearly articulated underpinning phenomenon of interest. In Mockford et al.’s review of public and patient involvement in the UK, ‘most studies relied on, and were driven by, current policy initiatives as their primary framework’ (Mockford et al., 2012, p. 35). Conklin et al., more damningly, highlighted ‘the continuing absence of a consensus on the definition of public involvement, and the variation in purpose of and approaches to involvement, either of which are often not made explicit’ (Conklin et al., 2015, pp. 160–161). With these linked findings as a starting point, this chapter takes an interpretive approach to discussing existing academic knowledge on citizen participation in healthcare (Greenhalgh et al., 2005). This section discusses empirical studies, while the next explores the literature’s conceptual basis more thoroughly.

The absence of evidenced outcomes or ‘impact’ from citizen participation is a recurring, and thorny, issue within this literature, playing both to concerns that participation is merely ‘tokenistic’, but also that it becomes devalued as a means to an end (particularly to cost-saving or organisational efficiency goals). Entwistle (2009, p. 1) discusses the risks of instrumentalising participation for wider organisational goals, and concludes ‘the notion of participation makes little sense if potential for influence is entirely lacking’. A few studies offer sympathetic interpretations of a lack of public influence through participation. In Anderson et al.’s study of London Primary Care Groups and Trusts, many of the weaknesses of public involvement exercises are attributed to a kind of complacency born of time constraints: ‘Those who accepted things as they were tended to focus their energies on the mechanisms of involvement rather than the mechanisms of change – they assumed the latter were in reasonable working order’ (Anderson et al., 2002, p. 61). Callaghan and Wistow’s case studies of English Primary Care Groups demonstrate two different approaches to public involvement – a dialogue approach versus a snapshot – but the authors find that both are underpinned by a ‘scientific rationalism’ by which ‘both boards gave primacy to their own “expert” knowledge’ (Callaghan and Wistow, 2006, p. 2299). Some studies highlight the presence of individual staff members who promote and support involvement; Harrison and Mort (1998) describe these as ‘participation entrepreneurs’. In other cases, individuals operate as a conduit for public views; Anderson et al. highlight the example of a diabetes support nurse who ‘completely ignored the formal processes of decision-making and learning in the PCG but sustained a shared process of learning through her informal network of professional contacts’ (Anderson et al., 2002, p. 61).

However, as Crawford et al.’s (2002) systematic review states, multiple papers conclude that staff are a crucial obstacle to the impact of involvement. Writing in the English context, Martin notes within the literature ‘a widely observed reluctance on the part of health professionals and managers to engage with the public and put into practice the outputs of public-involvement processes’ (Martin, 2008a, p. 1757). Harrison and Mort (1998) coin the term ‘technology of legitimation’ and offer an account of the way in which public involvement efforts can be used by manipulative managers:

the simultaneous construction of user groups’ legitimacy by the expression of positive views about them, and its deconstruction by reference to their unrepresentativeness and/or unsatisfactoriness as formal organisations constitutes a device by which whatever stance officials might take in respect of user group preferences or involvement on particular issues could be justified. (Harrison and Mort, 1998, p. 66)

In this interpretation, dilemmas of impact (attributed to staff members’ interference) are closely linked with dilemmas of representation. Questions of representation crop up frequently within the literature on participation in health, but are rarely satisfactorily answered. As one review states, many studies ‘had not provided an explicit definition or statement of how the public was operationalised for the analysis in question’ (Conklin et al., 2015, p. 156). Two dimensions of representativeness tend to recur in discussion and debate about public involvement: both can be seen as a response to the unfamiliarity of notions of representation where a formal process of authorisation is absent. Firstly, there is a demographic question, which Martin describes as ‘descriptive-statistical’ (Martin, 2008a). This essentially demands that representatives resemble those they represent in demographic characteristics (Pitkin, 1967). The absence of descriptive representation is, Warren (2009a) argues, a major flaw in citizen participation initiatives, which should be resolved by methods such as random selection of participants. A second, which is often hinted at but rarely elaborated on in academic literature, is a simple concept of ‘newness’ to civic activities; essentially one cannot be both ‘ordinary’ and one of ‘the usual suspects’. Harrison and Mort’s UK-wide study (1998) points to the uncertain, unstable legitimacy of user groups, and to the non-binding, informal manner in which they feed into decision-making. In their study of NICE’s Citizens Council in England, Davies et al. (2006) identified a move away from the authority of the Council – a deliberative body founded and recruited at considerable effort and expense – towards public opinion surveys and focus groups. Arguing that many studies identify that ‘health professionals … keen to retain control over decision-making, undermine the legitimacy of involved members of the public, in particular by questioning their representativeness’ (Martin, 2008a, p. 1757), Martin places the question of representativeness at the centre of his research. However, unlike analyses which identify a zero-sum power battle as the cause of failures, he points to ambiguity in policy objectives around involvement as creating the tension between staff and public representatives. Reconfirming the linked nature of dilemmas of impact and representation, in later co-authored work, Martin argues that demands for impact or demonstrable influence should be restricted so that a more representative sample of the population will take part (Learmonth et al., 2009). Alternatively, one study looking at young people in English hospitals explicitly argues for a ‘listening culture’, whereby issues can be raised informally, rather than formal projects of involvement (Lightfoot and Sloper, 2006). Young people, and other groups perceived as ‘hard to reach’, are often seen as better ‘involved’ through dialogue with trusted professionals, than through roles within formal mechanisms (Lightfoot and Sloper, 2006; Macpherson, 2008).

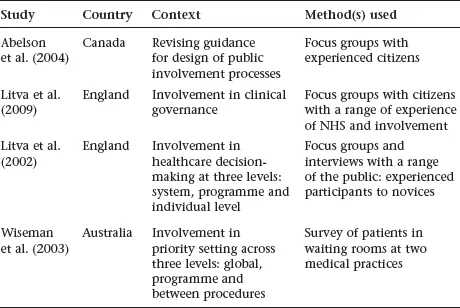

This concern with engaging ‘ordinary’ (Learmonth et al., 2009; Martin, 2008b) members of the public (implicitly those who do not already take part in involvement) has prompted a cluster of studies seeking public views on involvement in general (see Table 1.1). These studies include members of the public with a range of experiences, from the ‘unengaged’ to experienced participants. In seeking to speak for such a broad group, and in an explicit effort to move away from participants reflecting on their experiences, these papers are prone to broad conclusions which border on banal. Litva et al.’s article concludes simply: ‘The public has much to contribute, especially at the system and programme levels, to supplement the inputs of health-care professionals’ (Litva et al., 2002, p. 1825).

The recommendations offered in these four studies seeking public perspectives on participation in three different health systems are remarkably consistent. They tend to advocate a shift away from the goals of ‘citizen control’ (Arnstein, 1969) or ‘lay domination’ (Feingold, 1977), advocated by authors in the 1960s and 1970s. Thus Litva et al. (2009) promote ‘overseeing’ as an alternative to control. Wiseman et al. support partnership and collaboration:

Table 1.1 Studies of public perspectives on participation in health in general

Citizens in this study felt that they have a legitimate role to play in priority setting in health care but that this role must be a joint one involving other groups, namely clinicians, health service managers, and patients and their families. (Wiseman et al., 2003, p. 1010)

Litva et al. (2002) broadly concur, noting that citizens may be wary of having the final say. The desire to access an ‘ordinary’ perspective on participation has prompted these authors to broaden analysis away from case studies of practice, eliciting generalised ‘public’ perspectives on participation through focus groups and surveys. These advocate ‘weaker’ forms of participation, and a move away from the goal of citizen control.

Overall, empirical studies of public involvement in health since the late 1990s have had a consistent and closely linked set of findings. They have repeatedly found problems and inadequacies in the practice of participation in health, often revolving around the challenges of balancing concerns about (demographic) representation and the need to demonstrate impact on structures and services (Learmonth et al.’s (2009) ‘catch 22’). Something of a consensus has developed that participation should be ‘embedded’ into services in order to channel the views of as wide a range of the public as possible, even at the risk of sacrificing the goal of citizen control (Litva et al., 2009; Tritter, 2009; Tritter and McCallum, 2006). In the next section, we will explore the conceptual understandings of participation which frame these findings.

The conceptual basis of research on participation in health systems

Stating the indeterminacy of the concept of participation has become something of a lynchpin of introductory sections (Bishop and Davis, 2002; Bochel et al., 2008; Conklin et al., 2015; Crawford et al., 2002; Tritter, 2009). However, the literature has continued to grow apace, revolving around a range of compounds formed by adding a named group of participants (‘public’, ‘patient’, ‘citizen’, or ‘user’) to a type of activity (‘involvement’, ‘engagement’, or ‘participation’). The result is literature that shares a family resemblance (Wittgenstein, 1953) rather than a terminological grounding. One editorial for a ‘virtual special issue’ on public participation in health describes searching the archives of the journal Social Science and Medicine: ‘each of the search terms “public” and “community” was combined with each of the terms “participation, engagement, deliberation and involvement”’ (Tenbensel, 2010, p. 1). By and large this curious instability – resulting in what Rowe and Frewer (2005, p. 252) describe as ‘synonyms of uncertain equivalence’ – is given little attention within the literature. As one paper puts it, with little explanation, ‘involvement will be considered as a generic term that encompasses the notions of participation, consultation and engagement’ (Wait and Nolte, 2006, p. 152). Other papers choose an alternative umbrella concept and consider involvement as a subset (Rowe and Frewer, 2005). Perhaps the most common response to this discursive instability is to shift repeatedly and without explanation between different terms. As an illustrative example, O’Keefe and Hogg (1999) use ‘public participation’ in their title, select ‘user involvement’ as a keyword, ‘public involvement’ in their abstract, and in the body of the article shift apparently arbitrarily between ‘community involvement’, ‘user involvement’, ‘public involvement’, ‘user participation’, and ‘community participation’ (with the titular term ‘public participation’ neither defined nor used thereafter). Occasionally trends emerge whereby certain terms become particularly common in specific contexts or periods. For example, ‘patient and public involvement’ as an analytic category seems to be a predominantly UK-based construction associated with New Labour policy of the late 1990s and 2000s (Forster and Gabe, 2008).

The key tactic of authors struggling with the indeterminacy of the concept of participation has been to refer to a series of typologies of participation which have developed in the wake of Arnstein’s (1969) ‘ladder of participation’. As highlighted by Kuhn’s (1962) account of normal science, a specific set of approaches to a given research topic becomes standard practice, limiting its analytic and critical potential.

This leads to recurring themes within the literature and unquestioned approaches and definitions: the ubiquity of typologies of participation can be seen as just such an approach. Typologies are more generally acknowledged to ‘be seductive in their capacity to simplify thought’ (Weiss, 1994, p. 174). In the participation in healthcare literature this tendency is closely linked to definitional struggles; typologies have been one way to deal with the wide range of initiatives that profess to be ‘participation’. Table 1.2 sets out five typologies of public involvement from the literature which all concern themselves with defining the ‘level’ of invol...