eBook - ePub

Multidisciplinary Research on Teaching and Learning

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Multidisciplinary Research on Teaching and Learning

About this book

This collection indicates how research on teaching and learning from multiple scientific disciplines such as educational science and psychology can be successfully pursued by a co-operation between researchers and school teachers. The contributors adopt different methodological approaches, ranging from field research to laboratory experiments.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Self-Regulation and Instruction

1

Educational Processes in Early Childhood Education: Activities of Target Children in Preschools

Wilfried Smidt

The present study is a contribution to the topic of educational quality in preschools. This topic has been part of an extensive debate in Germany especially since the end of the 1990s (Tietze et al., 1998). For readers who are not familiar with preschool education in Germany, some characteristics should be briefly introduced. Generally, the ministries of social affairs of the 16 federal states carry the general administrative responsibilities for preschools rather than the educational authorities, who exclusively carry that responsibility for primary schools. In Germany, the discussion about educational quality within the field of early childhood education arose in the early 1990s as a consequence of problems that occurred from bringing together the early childhood education systems of Western Germany and the former Germany Democratic Republic after the reunification (Tietze et al., 1998; Tietze & Cryer, 1999). Changing family structures (e.g., growing rates of parental mobility, increasing risk of poverty) are also considered to have played a part in generating discussion about the importance of quality in preschool education (Esch, Klaudy, Micheel, & Stöbe-Blossey, 2006). Another important factor was the relatively poor performance of German pupils in international school benchmarking studies (e.g., Programme for International Student Assessment [PISA], German PISA-Consortium, 2001). This poor performance is considered to be associated with the need to improve the quality of education in preschools (Roux & Tietze, 2007). Last but not least, curricula in early childhood education in preschools were successively introduced in all German federal states in order to enhance the quality of educational practice in preschools (Diskowski, 2008; see also Smidt & Schmidt, 2012, for a critical overview of empirical findings of the implementation of early childhood curricula). In fact, there is strong evidence for the predictive importance of a good quality of preschool education for the development of cognitive and socio-emotional child-related outcomes (e.g., Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2009; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Early Child Care Research Network [NICHD ECCRN], 2006).

There are different ways to conceptualize educational quality. One common way of defining quality involves an approach that distinguishes between process quality (e.g., teacher-child interactions) and structural quality (e.g., child-staff ratio, teacher experience; Cryer, 1999). This paper will focus on the quality of educational processes because these “proximal processes [are] the primary engines of development” (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006: 798). Educational process quality focuses, for instance, on activities and interactions of children and preschool teachers as well as on the schedule of daily routines in preschools. Another important feature that has to be introduced stresses the distinction between educational process quality measured at the preschool level (e.g., with the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale – Revised Edition, ECERS-R; Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2005) and such quality examined at the level of single children (target children) within the preschool class (e.g., with the Observational Record of the Caregiving Environment, ORCE, NICHD ECCRN, 1995). On both levels, educational quality can be captured with high-inferential (i.e., with ratings) and low-inferential (i.e., frequency-based) measures (Brassard & Boehm, 2007). Despite intensive discussions about educational preschool quality with regard to the German preschool system, there is still a strong need for research to address the nature and number of activities that preschool children are involved in. This is especially true for longitudinal research because children’s developmental progress across the preschool years is linked to changes in children’s activities and interactions (Hyson, Copple, & Jones, 2006). This study therefore examined the development of children’s activities in the first, second, and third years of preschool (see Smidt, 2012, for additional analyses).

Theoretical background

Research on educational process quality in preschool can be based on different theoretical approaches that concentrate on specific issues. Bronfenbrenner’s (e.g., Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Bronfenbrenner, 1993) eco-systemic framework allows the quality of educational processes to be viewed from the standpoint of being embedded in preschool classes, which can be described as microsystems. A microsystem depicts a “face-to-face setting” (Bronfenbrenner, 1993: 15), which is defined by specific patterns of activities and interactions. Microsystems are integrated into more extensive systems (meso-, exo-, and macrosystems). This theory also stresses a longitudinal perspective on educational process quality as it postulates that proximal processes (i.e., activities and interactions in preschool classes) vary as a function of time: “As children grow older, their developmental capacities increase both in level and range; therefore, to continue to be effective, the corresponding proximal processes must also become more extensive and complex to provide for the future realization of evolving potentials” (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006: 798).

Another theory emphasizes didactical features of educational work in preschool classes. The offer-and-use model (Klieme, Lipowsky, Rakoczy, & Ratzka, 2006; Helmke, 2008) was originally developed for research on the quality of school teaching and then transferred to educational quality in preschools (Kuger & Kluczniok, 2008). One major assumption is that the learning opportunities that are offered must be used by the children to become effective.

With interaction theories, it is possible to describe the relationship between preschool children and their teachers in more depth. In particular, the crucial role of the educational preschool staff and the importance of a longitudinal view can be highlighted. Important interaction theories, which are critical for conceptualizing developmentally appropriate support of preschool children, go back to the ideas of Vygotsky (1987), who introduced the concept of the zone of proximate development. With this zone, the difference between children’s ability to manage tasks with and without the support of competent others (e.g., preschool teacher, older children) is described. In this context, interaction processes between preschool teachers and children become crucial (Forman & Landry, 2000). Based on the Vygotskian approach, several similar concepts that refer to the encouraging and supportive role of the preschool teacher were developed (i.e., scaffolding: Wood, Wood, & Middleton, 1978; guided participation: Rogoff, 1998; sustained shared thinking: Siraj-Blatchford, 2009). The aforementioned interactional approaches may also be particularly appropriate to be applied from a longitudinal perspective on educational processes due to their emphasis on providing developmentally appropriate support of children. These approaches have been responsible for adaptions that have been made in educational processes in preschools as good educational practices have recommended (e.g., Tietze & Viernickel, 2007; Bredekamp & Copple, 2009).

A final theoretical approach that should be mentioned relates to the domain specificity of educational processes. In accordance with theories that emphasize the domain specificity of children’s knowledge acquisition (e.g., Wellman & Gelman, 1998; Carey & Spelke, 1993), the domain-specific nature of educational processes is stressed. For instance, supporting children can be realized in domains such as early literacy and early numeracy (Rossbach, 2005; Cullen, 1999). In this regard, it is assumed that beginning domain-specific promotion early in children’s educations can benefit their development of specific competencies (Rossbach, 2005).

The introduction of different theoretical approaches may raise questions about what constitutes good educational process quality. Although there are no clear recommendations with regard to specific “compositions” of activities in order to ensure good process quality, in agreement with pertinent standards (e.g., Bredekamp & Copple, 2009), good educational process quality can be said to exist if there is secure and health-supporting care, a developmentally appropriate support of children across a broad range of domains, a positive climate in the preschool class, and an encouraging and scaffolding role played by preschool teachers (Tietze et al., 1998).

The current state of research

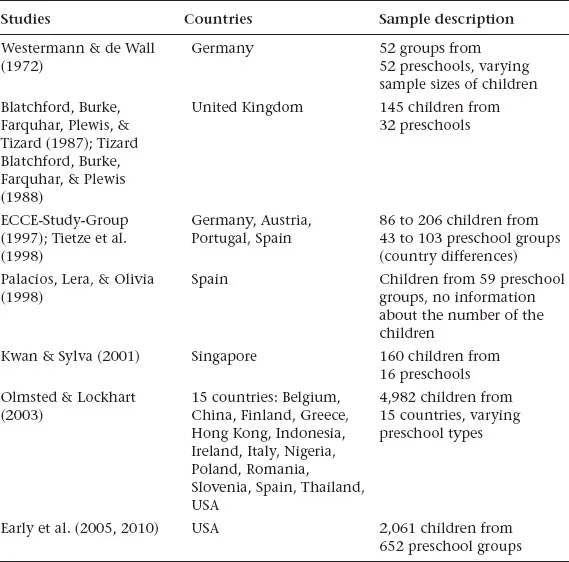

Regarding the nature and extent of activities that preschool children are involved in, there are only a few studies that have provided empirically sound information. However, widening the view to an international perspective, there is some research that should be considered. The key information about these studies is summarized in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Study overview

Some studies found that transitions (from one activity to another), waiting periods, and organizational and care activities (i.e., hand washing, going to the bathroom) altogether accounted for at least 20%, sometimes over 30%, of the time during which the children were observed (Early et al., 2010; Olmsted & Lockhart, 2003; Kwan & Sylva, 2001; Tietze et al., 1998; ECCE-Study-Group, 1997). In contrast to these findings, the results of a study conducted by Tizard et al. (1988) revealed a different picture: Altogether, the aforementioned activities took up only about 14% of the observation time. Even smaller was the proportion found by Palacios et al. (1998) in a Spanish study in which these activities accounted for only 7% of the observed time. Regarding the last study, however, it remained somewhat unclear how the activity categories in question were operationalized. Another activity complex referred to role playing, creative activities (i.e., art, blocks, construction games), and music. Altogether, these activities accounted for approximately 20% to 30% of the observation time (Early et al., 2010; Olmsted & Lockhart, 2003; Tietze et al., 1998; ECCE-Study-Group, 1997; Westermann & de Wall, 1972). However, the pattern of results was not consistent. In contrast to these results, a few studies found substantially lower proportions of these activities (Palacios et al., 1998; Kwan & Sylva, 2001). Fine and gross motor activities, which were considered in several studies, comprised another broad part of the children’s activities. The proportions of these activities varied greatly depending on the study; altogether, fine and gross motor activities accounted for percentages between 16% and 38% of the observation time (Early et al., 2010; Early et al., 2005; Olmsted & Lockhart, 2003; Kwan & Sylva, 2001; Palacios et al., 1998; Tietze et al., 1998; ECCE-Study-Group, 1997).

With regard to the amount of early literacy, early numeracy, and natural science activities of children in preschools, the results of the existing research were also quite inconsistent. In a study conducted in Germany, only language-related activities were captured; they accounted for 6% of the observed time (Tietze et al., 1998). By contrast, findings from Spain and Portugal revealed a much larger amount of children’s language-related activities with percentages of 15% and 17%, respectively (ECCE-Study-Group, 1997). In a study carried out in 15 countries, language- and numeracy-related activities as well as natural science activities together accounted for 9% of the observed time (Olmsted & Lockhart, 2003), whereas Kwan and Sylva (2001) found that these activities comprised 19% of the time in preschools in Singapore. Relatively high proportions of early literacy (17% to 19% of the observed time), early numeracy (8%), and natural science activities (10% to 11%) were detected in a large American study (Early et al., 2005, 2010). Similar results for early literacy and early numeracy activities were also reported by Tizard et al. (1988). The largest amount of early literacy, early numeracy, and natural science activities was found by Palacios et al. (1998): Altogether, the above-mentioned children’s activities took up slightly over 50% of the observation time.

A few studies have also captured the frequency of parlor and board games with the percentages of observation time ranging from 1% to 5% (Tietze et al., 1998; ECCE-Study-Group, 1997). Very occasionally (maximum 1%), technology and media-related activities (i.e., use of computer and videos, listening to CDs) were observed (Olmsted & Lockhart, 2003; Tizard et al., 1988). All of the aforementioned studies referred to cross-sectional findings, but there has been surprisingly little research concerning the longitudinal development of children’s preschool activities over time. In an older study conducted by Blatchford et al. (1987), early literacy and early numeracy activities increased signif...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I Self-Regulation and Instruction

- Part II Language Learning and Language Comprehension

- Part III Mathematics and Science Education

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Multidisciplinary Research on Teaching and Learning by W. Schnotz, A. Kauertz, H. Ludwig, A. Müller, J. Pretsch, W. Schnotz,A. Kauertz,H. Ludwig,A. Müller,J. Pretsch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Teoría y práctica de la educación. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.