eBook - ePub

Collective Memory and National Membership

Identity and Citizenship Models in Turkey and Austria

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Collective Memory and National Membership

Identity and Citizenship Models in Turkey and Austria

About this book

This study seeks to explain the impact of historical narratives on the inclusiveness and pluralism of citizenship models. Drawing on comparative historical analysis of two post-imperial core countries, Turkey and Austria, it explores how narrative forms operate to support or constrain citizenship models.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Collective Memory and National Membership by Kenneth A. Loparo,Meral Ugur Cinar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Questions of citizenship and minority rights take center stage in policy debates all around the world. Reactions to quests for inclusion and recognition vary considerably however. While in some countries such demands are found legitimate in others they fail miserably. Who gets to join and who is to be excluded? Whose ethnic identity is part of the cultural landscape and whose is deemed undesirable or even treacherous? Answers to these questions are fateful for the lives of many. These answers however are never confined to the present. Nor are they future-oriented only. They invoke perceptions of the past that political communities hold about themselves. Perceptions of the past influence how national communities perceive themselves and what they see as imperative or acceptable within the national framework.

This book is concerned with the role collective perceptions of the past play in constructing, maintaining, and challenging views of citizenship and national identity. Yet it also takes variation in the visions of the past seriously. It aims at understanding how much of the disparity in the way citizenship questions are approached can be explained by the differences in visions of the past. Drawing on comparative historical analysis of two post-imperial core countries, Turkey and Austria, it explores how differences in perspectives on the past inform citizenship debates. It looks at the ways in which different forms of historical narratives foster certain citizenship models and create resistance against others. By doing this, it attempts to develop a conceptual framework that can facilitate our thinking beyond the two cases when analyzing the history-identity nexus at the collective level.

The relationship between visions of nationhood and collective views of the past merits further scholarly attention. First of all, we need to take into consideration that the interpretation of history matters at least as much as the historical trajectory itself. This point is overlooked more often than one would expect. Studies of different nationhood and citizenship patterns so far have focused on the historical legacy and timing and sequencing of historical trajectories to account for variation in national traditions. They have mostly either looked at whether the state came before the idea of the nation or whether the state was an imperial core country or not.

The insufficiency of such theories becomes especially evident in the comparison between Turkey and Austria.1 Turkey and Austria were established in the first half of the 20th century, on post-imperial territories with multiethnic populations. They are post-imperial core countries. The preceding empires in both cases had a very similar life span, both founded in the late 13th century and collapsed at the end of World War I. Turkey and Austria, share imperial pasts with similar life spans but differ in their approaches to minority rights. Austria recognizes different ethnicities, Turkey does not. Turkey has one official language, Austria has multiple. Extant studies cannot explain the variation in treatment of minorities in Turkey and Austria. The past does not, on its own, explain difference in citizenship policies. Neither the past nor accompanying visions of nationhood are passively or automatically inherited and passed from one generation to another. History writing is an active practice. Thus, we need to pay attention to how the past is interpreted and institutionalized.

The past, which reaches us through interpretative processes, is conveyed through narratives. Narratives attribute separate, objective facts, the continuity of a subject.2 In Brockmeier’s words: ‘If I do not only want to count the photographs from my past collected in that box and not only name the persons they show, but also want to point out why they mean anything to me at all, then narrative becomes the hub of my account.’3

The existing literature on the cognitive and social importance of narratives can help us construct fruitful research agendas built on the relationship between history, narratives, and political identity. Paul Ricoeur shows us that our sense of temporality is linked to narratives. In Narrative Time,4 he holds that narrative plots, with their beginnings and ends, enable us to gain a certain sense of time that goes beyond chronology. With a similar concern, Hayden White argues that annals and chronicle forms of historical representation are not failed anticipations of ‘the fully realized historical discourse that the modern history form is supposed to embody.’5 Instead, they are alternatives to modern history writing which comes in narrative form. He argues that it is the modern historiographical community which has distinguished between annals, chronicle, and history forms of discourse on the basis of their attainment of narrative fullness or failure to attain it. White claims that historical narratives are not scientifically superior to annals and chronicles but historical narratives are dominant because narrative form ‘speaks to us, summons us from afar (this “afar” is the land of forms), and displays to us a formal coherency that we ourselves lack.’6 White adds that ‘the historical narrative, as against the chronicle, reveals to us a world that is putatively “finished,” done with, over, and yet not dissolved, not falling apart. In this world, reality wears the mask of a meaning, the completeness and fullness of which we can only imagine, never experience.’7

In addition to its value in giving cognitive order to people’s comprehension of time and events, narratives also play a crucial role in the realm of ethics and morality. According to Alasdair MacIntyre narratives are ethical tools. Narrative is an essential tool for a good life, full personhood, and moral integrity. It is through stories that we make sense of our morality. Humans understand what a good, or virtuous, life is through narratives about their lives. MacIntyre’s narratives are connected to what he calls living traditions. He defines a living tradition as ‘a historically extended, socially embodied argument, and an argument precisely in part about the goods which constitute that tradition.’8 In this sense, these traditions are embedded in narratives and are transferred to new generations in the form of storytelling. In a parallel fashion, Charles Taylor states that ‘in order to have a sense of who we are, we have to have a notion of how we have become, and of where we are going’ and we only reach this notion via narratives.9 Taylor maintains that our sense of what is good is woven into our understanding of our lives as unfolding stories and it is therefore also shaped through narratives.

The central role played by narratives does not only manifest itself at the individual level. Human beings do not only understand but also evaluate and communicate social phenomena in narrative form. Polletta, who shows us the central role of storytelling in social movements, argues that narratives are evaluative since we assess our options through them.10 These narratives are also guiding and even demanding on issues concerning national identity. Narratives’ roles as sources for guidance and commitment are especially visible in the case of historical narratives. As Moreno and Garzon argue, a historical narrative transmits the dual message that first, the people of the nation have existed in the past and still exist in the present and, second, that this legacy from the past demands a commitment to carrying out a future plan. According to Moreno and Garzon, legacy, commitment, and political plan are the three basic premises of nationalist ideologies. These premises constitute the message implicit in the historical narrative sustaining them.11 Bridger and Maines also argue that because narratives provide a link between the past, present, and future, they are an important interpretive and rhetorical resource that people draw upon in times of crisis and rapid change. Like Polletta, they contend that narratives reduce the choices of alternative meanings attributed to events.12

These studies establish a strong link between personal and collective identity as well as action. What inferences can we make from their findings for the study of nationalism and citizenship? The narratological character of history means that we need to focus on narratives that create a web of meaning around separate images and events of the past and facilitate the transmission of perceptions of the past. Narratives of collective history are crucial in instigating trust, worth, and social capital among collectivities.13 As a result, they influence national self-perception, including confidence in assimilatory powers or in granting minorities rights. Therefore, we cannot understand traditions of nationhood or notions of citizenship without examining the central role that historical narratives play in disseminating and reproducing them.

In addition to the interpretative and narratological dimensions of the relationship between history and national identity, we also need to account for the variation in historical narratives and corresponding citizenship models. Historical sequences are not naturally tied together through predetermined storylines. Rather, they can be emplotted in more than one plausible way, so as to provide different interpretations of those events and endow them with different meanings.14 As Assmann aptly asserts, ‘societies imagine self-images and continue an identity through the sequence of generations, by developing a culture of remembrance; and they do that ... in very different ways.’15 So far, studies that have acknowledged the role of the construction of the past in the service of nation-building and nationalist ideology have generally done so either at the abstract theoretical level or within the context of single cases.16 They have not sought to discern a pattern in the forms of narration that can facilitate the construction of a theory on the association between forms of historical narratives and different identity projects.17 In order to be able to compare different forms of historical narratives and their consequences and in order to build a theory that has implications for cases outside the ones under investigation, we need to broadly categorize historical narratives.

This book is written with the concerns above in mind. It focuses on the relationship between forms of historical narratives and visions of political community. It starts with a typology of narrative forms. In developing this typology, I derive the categories from Pepper’s World Hypotheses.18 This typology provides a useful conceptual framework for the analysis of historical narratives. The categories are intuitive and cover the field of possibilities in which forms of narratives can be typified. These categories are organicism, contextualism, and mechanism. Before describing the proposed link between narratives forms and citizenship models, I will first outline each category’s distinct features.

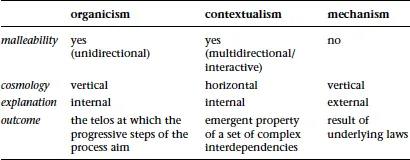

In the organicist form of narrative, particulars within the historical field are viewed as elements of synthetic processes. The whole is more than the sum of its parts. Explanation is integrative and goal-oriented. The final structure is the telos at which the progressive steps of the process aim.19 In contextual accounts, events and the interaction of agents are explained within the historical setting in which they take place. Contextual narratives treat historical units as dynamic elements that are in a web of relationship with other historical units. In the mechanistic form, entities are static; their behavior is determined by laws that govern them.20

The three forms vary along certain lines. One important dimension of variation is the malleability of historical entities. As opposed to mechanism, which takes historical entities and relationships as given, and as results of predetermined forms of interaction between these preconfigured entities, both contextualism and organicism view history as something that is open to change. In a mechanistic form of narrative, things are what they are and we can only explain the external relationship between them. Meanwhile, in organicism, elements in history are not taken as given and the explanation is not external to the process. In an organicist narrative, things become what they are through the teleological subsuming of smaller entities into larger ones. In a contextual narrative, things also become what they are, but through the interrelationship of different entities. Unlike organicism, in the case of contextualism, change comes along not as a result of a teleological process, but as part of an interactive process, which allows the coexistence of different entities without collapsing them into a single whole. Consequently, contextualism and organicism can be further differentiated based on how they approach change, or the transformation of historical units. Organicism is unidirectional, goal-oriented and teleological.21 In organicist accounts, fragments are connected and they have an internal drive toward the integrations which complete them.22 This constant integration of narrative details, the emphasis on the telos, as well as its anticipation differentiates organicism from contextualism.

Contextualism assumes that ‘reality consists of textured layers ... as rope is constructed from strands of thread woven together.’23 There is still an interrelationship between different agents of history but this relationship is not unidirectional. In other words, the flow of events is not only in accordance with and in the direction toward the telos that is to be reached. Since the relationship is not explained as teleological, in which smaller entities are melting into the greater whole, interaction and interrelationships among different agents are common. Things become what they are through the interrelationship and coexistence of different things. They are transformed but without losing their distinctiveness.

As a result of these differing characteristics, Pepper argues that contextualism has a horizontal cosmology, while mechanism and organicism, have a more vertical cosmology. One either tries to get to the ‘bottom of things’ (as it is the case in mechanism where one tries to find the underlying law), or to the ‘top of things’ (as it is the case in organism, where one tries to reach the telos, or the greater whole in the story).24 Unlike mechanism and organicism, contextualism treats the relationship between different units horizontally in the sense that their relationship is interactive and reciprocal, and all relevant units have agency.

Implications for citizenship

Having outlined the defining features of each category, we can now move on to the citizenship models fostered by each category. I propose, and will later demonstrate, that each category has different implications for the level of inclusiveness and pluralism of citizenship models. The organicist form of historical discourse leads to an inclusionary but homogenizing identity model, which is assimilatory in nature. The organicist narrative, with its elements of change, development, and integration, justifies an inclusionary national vision. But inclusion is conditional upon internalizing cultural characteristics of the dominant group. Organicism is homogenizing because it does not allow agency to smaller units in history.

Table 1.1 Typology of narratives

Contextualism legitimates the view that more than one group of people can coexist within the boundaries of the nation provided that these groups have been living there through the historical periods that are deemed relevant. Hence contextualism is conducive for a pluralist and inclu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Turkish Historical Narrative

- 3 Historical Narratives in Action: The Turkish Case

- 4 The Austrian Historical Narrative

- 5 Historical Narratives in Action: The Austrian Case

- 6 Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

- Appendix: Periodization of Political History for Textbook Selection

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index