- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This cultural and political study examines British perceptions and policies on India's Afghan Frontier between 1918 and 1948 and the impact of these on the local Pashtun population, India as a whole, and the decline of British imperialism in South Asia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ramparts of Empire by B. Marsh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The North-West Frontier and Post-War Imperialism

1

The North-West Frontier: Policies, Perceptions, and the Conservative Impulse in the British Raj

The East India Company’s annexation of the Punjab in 1849 looms large as a pivotal moment in the creation of the Victorian British Raj. The seizure of Ranjit Singh’s former kingdom brought with it the resources that would make the region India’s great granary, a Muslim and Sikh population that would provide the backbone of the post-1857 Indian Army, and the administrative raw materials for the “Punjab School” of the Indian Civil Service, the epitome of British paternalism in South Asia. Beyond this, however, the accession of the Punjab to the Company meant that the British now inherited the Sikh state’s loose and recent paramountcy over the ill-defined territory stretching from the east bank of the River Indus to the Khyber Pass. Eventually ranging from Chitral in the north to Waziristan and Dera Ismail Khan in the south, these Afghan borderlands with their large Pathan population would prove to be one of the abiding obsessions of the British in India. Although the issues that the British encountered on the North-West Frontier, such as indigenous unrest and raiding, Afghan intrigues, and the specter of Russian expansion, were, in the words of one author, an “imperial migraine,” control of the region was also viewed as central to Britain’s imperial power and prestige. The Frontier was the “anvil,” in the words of the Viceroy Lord Curzon, on which the future of the British Empire was daily forged.1

This chapter provides an overview of the region and the creation of British perceptions and policies about the Afghan Frontier and its inhabitants over the course of the nineteenth century. After considering the ways in which the British came to the see the Frontier as a uniquely strategic region and the Pathans who lived there as singularly violent, religious, independent, and unchanging, the chapter provides background on the two key constituencies charged with administering, and much of the time, formulating policy on the North-West Frontier: the Indian Political Service and the leadership of the Indian Army. It contends that, as a group, these two bodies tended towards a deeply conservative and paternalistic view of the Pathans who lived in both the administered and “tribal” areas of the Frontier. Far from being mere martinets tasked with carrying out policies dictated from London, Delhi, or Simla, the administrative structures of the British Government of India meant that “the men on the spot,” or those who had previously served on the Frontier, sometimes for decades, had a great deal of influence over the way in which the region and its people were perceived at the highest levels of government. Lastly, this chapter deals with the extraordinary durability of British ideologies about the Frontier that originated in the specific contexts of the nineteenth century and persisted into the inter-war period and beyond, a resiliency that was to have a profound impact on the events examined in this study.

Experience, perceptions, and policies, 1808–1919

Although the British began their administrative odyssey with the Pathans who lived between the Indus and the Khyber in 1849, the origins of their long and complicated relationship with the Afghan borderlands began 40 years earlier. The first Briton to encounter what would become the Indian Empire’s North-West Frontier was the renowned “romantic” administrator, Mountstuart Elphinstone, in 1808. The entire region was then under the sway of Shah Shuja’s Afghan kingdom based at Kabul and Peshawar, and Elphinstone was charged with opening relations with the soon-to-be-deposed Amir. A well-educated and erudite individual, Elphinstone thoroughly documented his time in Peshawar, a record revealed in both his private correspondence with the East India Company and in his book, An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul, published in 1815. Elphinstone’s appraisals of the society he encountered, and the worldview they reflected, were incredibly influential and constituted the foundation of all subsequent British understandings of the area and its inhabitants.2

As the sole major work on the region in the first decades of the nineteenth century, Elphinstone’s writings became the hegemonic text for Britain’s colonial knowledge of the Frontier. Informed by the intellectual world of the late Scottish Enlightenment and its emphasis on the universality of the human experience, Elphinstone believed that the men he encountered in the rugged Afghan borderlands were analogous to the Highlanders of his native Scotland. Two aspects of this analogy were particularly important: Elphinstone’s interpretation of Pathan social organization and his views on the Pathan “character.” Drawing upon his Scottish context and, it should be noted, influenced by his indigenous informants, Elphinstone sought to categorize the society he witnessed along lines similar to the Highland clans, organizing the various groupings into tribes and subtribes. Elphinstone’s view of the Pathan character was also in line with his Highland analogy. He wrote that “their vices are revenge, envy, avarice, rapacity and obstinacy; on the other hand, they are fond of liberty, faithful to their friends, kind to their dependents, hospitable, brave, hardy, frugal, laborious, and prudent.”3

Pathan society, which the British initially sought to define and later hoped to control, varied greatly, and the forms it took were immensely different over geography and time. The Pathan culture in the Vale of Peshawar was different from that in the passes of the Hindu-Kush or the deserts of southern Afghanistan. Furthermore, as recent anthropological scholarship has emphasized, cultural norms and practices are anything but stagnant, waning and waxing over time.4 Elphinstone’s appraisal was deeply flawed, mistaking fluidity for permanence and reducing the people of the region to a single essential “character.” Yet, it also reflected some level of the reality as he saw it. As anthropologist Charles Lindholm notes about the impulse to disregard all British era ethnography: “Not only would this position eliminate as ideologically corrupt some of our most important sources on the Pathans, it also has a more insidious significance. Such a viewpoint does not give any credit to Pathan culture as an autonomous structure, which is perfectly capable of impressing itself upon the observer.”5

Based on Elphinstone’s account, but reified and corroborated by subsequent travelers, soldiers, and administrators, the British came to understand the structure of Pathan society in the Frontier region as one that fell into the category of “segmentary lineage,” divided into a hierarchy of tribes (tarbar), clans (khels), sections (plarina), and families. These groups defined themselves through their patrilineal descent from a mythical common male ancestor. Within these groupings, Pathan society in the Afghan borderlands was and is notable in that it is generally acephalous, with no distinct internal hierarchy or hereditary leadership.6 Elphinstone was aware that unlike the Scottish clans with their loyalty to large landowning families, the Pathan tribes were governed by “Pashtunwali,” a tribal code based on egalitarianism and independence.7 Certain families possess more prestige than others, but in many ways it is an “untrammeled democracy,” with each man considering himself equal, if not superior, to his neighbor.8 In this essentially egalitarian society, the headmen or maliks, who fulfill the role of elder rather than chief of each tribe, often enjoy their position by dint of their heredity, but just as often a headman possesses his rank as a result of personal bravery, wisdom, or strength. Ultimately, the entire social structure is premised on “equality, individualism, and fierce competition.” Lastly, since Islam, rather than a political structure, stands as a primary tie within Pathan tribal society, religious leadership often comes to the fore in times of stress or war.9

When Elphinstone wrote about the Pathan’s “fondness for liberty” in the early nineteenth century, he identified this trait as a positive attribute. Sir Olaf Caroe, one of the premier Frontier officers of the twentieth century, noted that Elphinstone viewed the Pathans not through the eyes of a would-be-conqueror but as someone looking for possible allies in the subcontinent. Caroe noted that Elphinstone’s views were shaped by the fact that he met the Pathans “before they had become embittered by a long succession of expeditions and war, and he felt intuitively that there was a bond to be forged between ‘them’ and ‘us.’”10 Later, however, the British would view this “predilection for independence” in an increasingly negative context, joining it to the vices of “revenge, envy, avarice, rapacity and obstinacy” that Elphinstone had also identified.11

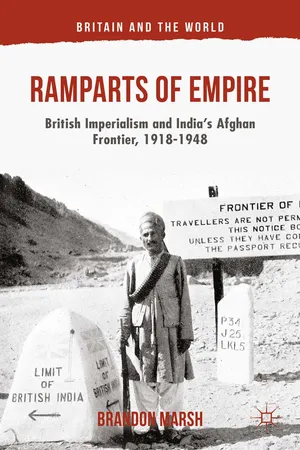

Image 1 The Khyber Pass, early 1930s

The “long succession of wars” west of the Indus began with the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1839–1842. This conflict constituted one of the greatest debacles and defeats in British imperial history. The war emanated from British fears of Russian expansion in Central Asia, or, as Kipling dubbed it, the “Great Game.” Convinced that “if we do not stop Russia on the Danube, we shall have to stop her on the Indus,” the British invaded Afghanistan with the goal of installing a pliant Amir on the throne in Kabul.12 The incumbent ruler, Dost Mohammad, in fact preferred an alliance with Britain to one with Russia, but he also wanted to regain his winter capital of Peshawar, which the powerful ruler of the Punjab, Ranjit Singh, had seized in 1818. Aware of Dost Mohammad’s claim and influenced by faulty intelligence, the East India Company, which had an alliance with Ranjit Singh, concluded that the Afghan ruler was an enemy who should be overthrown. The initial conflict was brief, and the British soon occupied the Afghan capital. The victory, however, was short-lived, and after surviving a long siege by Akbar Khan, the son of Dost Mohammad, the British were obliged to retire towards Jalalabad and thence to India. In the process of this retreat, carried out in the middle of the winter and led by incompetent officers, the British and their camp followers were massacred by the tribesmen who guarded the narrow mountain passes. Of a combined 16,000 soldiers and followers, only one Englishman, William Brydon, an assistant surgeon, made it to Jalalabad in a scene immortalized in Elizabeth Butler’s painting.13

This utter disaster served to confirm the British view that the Pathans were, to put it mildly, fond of their liberty. It also sowed the belief that the Pathans, as a race, were bloodthirsty and duplicitous. The vanquished Army of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- Part I The North-West Frontier and Post-War Imperialism

- Part II The North-West Frontier and the Nationalist Challenge

- Part III The North-West Frontier and the End of Empire

- Conclusion: The End of British Rule and the Frontier Legacy

- Select Bibliography

- Index