- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Most sociological work on football fandom has focused on the experience of men, and it usually talks about alcohol, fighting and general hooliganism. This book shows that there are some unique facets of female experience and fascinating negotiations of identity within the male-dominated world of men's professional football.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Female Football Fans by C. Dunn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Service Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Abstract: Carrie Dunn explains her own history as a football fan, which set the context for her research into female fans’ experiences in England. She sets the context of the ‘malestream’ academic football research, which concentrates heavily on issues of masculinity and deviant hooligan behaviour, and makes female fans invisible.

Dunn, Carrie. Female Football Fans: Community, Identity and Sexism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

DOI: 10.1057/9781137398239.0003.

DOI: 10.1057/9781137398239.0003.

About this chapter

I begin this book with a spot of reminiscence – explaining my own history as a football fan; yes, a female football fan. My own experiences partially set the context for my research into female fans’ experiences in English football; the other key element of the background is the ‘malestream’ academic football research, which concentrates so heavily on issues of masculinity and deviant hooligan behaviour, and makes female fans invisible. I outline just what the body of fan research says about women so far – and pinpoint just where my findings can start to fill in the gaps.

My life as a football fan

In most forms of popular culture, the ‘fan’ is invariably assumed to be female. Yet in football the opposite is true. The football ground is assumed to be a male domain, and the football fan is assumed to be male, with team allegiance frequently passed on from father to son.

However, female football fans do exist; and I know this because I have been a football fan since childhood. My father was a keen football fan, following Luton Town, attending matches regularly and bringing home memorabilia for me, before taking me along with him at the age of seven. From the age of nine, I had my own season ticket; from the age of sixteen I began travelling to away games, alone, with friends or with my father.

My awareness of the gendered concept of football fandom was non-existent until I was a teenager. My female friends at secondary school were entirely uninterested in a sport that took up every single Saturday, and were not at all understanding about my lack of availability for weekend social excursions. Very occasionally I would be on the receiving end of sexist heckles as I walked to my seat. When I began to consume more football-focused media, I realised that their intended audience was male; even when I read and delighted in Nick Hornby’s seminal Fever Pitch (1992), some of his analyses of his love for the game jarred with me.

When I was researching my master’s dissertation in English literature, I chose sports auto/biography as the focus. As I read more accounts of players’ and supporters’ relationship to football, I felt that my own experience was not being reflected back at me. This is not just the case in popular auto/biography and the mass media. Historically, academic studies of football supporters have invariably taken the white, straight, working-class man as the normal fan; anything else is presumed abnormal, and since the establishment of the Sir Norman Chester Centre for Football Research (later the Centre for the Sociology of Sport) at the University of Leicester in 1987, that fan has been the focus of even closer research, usually within the context of hooliganism and the reasons for violent disorder (e.g., Dunning, 1999; Williams et al., 1984; Williams and Perkins, 1997).

As I will show in this book, researchers into football have been largely male (with a few exceptions), and they assume that the football supporter is also male – someone similar to them. Even self-confessed ‘post-modern’ researchers such as Steve Redhead have focused on football’s ‘lad culture’ and the way in which young men are ‘fathered’ by their sport of choice, and then mention women’s long-term involvement in the game in passing, calling them ‘marginalised’. Writers across genres consistently explain football fandom as a desire to consolidate one’s masculinity – for example, in Fever Pitch Nick Hornby explains his fandom as a quick-fix of masculinity; academic Garry Robson (2000) explains ‘Millwallism’ partly as a harking back to older values of masculinity – or a wish to become part of an entirely male hooligan ‘firm’; and Colin Ward’s (1989, 1997, 1998, 2000) series of eyewitness accounts of hooliganism, or the Brimson brothers’ (1996, 1997) autobiographical accounts.

The obvious questions that have not yet been addressed are: why, then, do women become football fans; and what do they get out of it? This has been the driving intent behind my own research: to gauge the experiences of female football fans, to offer some potential explanations as to why they perceive these experiences in particular ways and to produce a qualitative study of the life story narratives they produce.

A brief history of female football fandom

The masculinity of sport has been enshrined in social apparatus, including the church and school system. The concept of ‘muscular Christianity’, rooted in the New Testament, is thought to have first appeared in an 1857 review of Charles Kingsley’s novel Two Years Ago, and later used to describe Tom Brown’s School Days, an 1856 novel about life at Rugby by Thomas Hughes. Both writers were labelled ‘muscular Christians’, and the definition was extended to their work – adventure novels with high principles and manly Christian heroes. The idea created an association among physical strength, religious certainty and one’s ability to shape and control the world (Hall, 1994: 7).

Hughes and Kingsley’s inspiration was the English public school system, in particular Dr. Arnold’s tenure at Rugby from the mid-1830s, during which he developed a concern that a lack of supervision would lead the boys into vice and a non-Christian way of life. Arnold’s near-contemporary biographers explained that he was ideally suited to the headship of a major school because of his own ‘physical vigour and activity’, and his encouragement to the pupils to participate in sport, which he saw as ‘essential to a boy’s true development’ (Selfe, 1889: 37).

Hughes and Kingsley saw themselves as social critics, and believed that asceticism and effeminacy had gravely weakened the Church of England. To make the church a suitable supporter for and partner of the expanding British Empire, they wanted it to demonstrate more ‘rugged’ and ‘manly’ qualities. Prominent figures such as G. Stanley Hall warned of the ‘woman peril’ to the church, creating a ‘feminising’ influence on hymns, music, imagery and ministry (Putney, 2001: 3). This campaign was not limited to England or the empire; they also exported their call for more health and manliness in religion to America, where their ideas failed to catch on immediately due to factors such as Protestant opposition to sports and the popularity of feminine iconography within the mainline Protestant churches. However, in the 1890s President Theodore Roosevelt began to stress the importance of boys participating in sport as preparation for future national service, developing in them the ‘Christian’ qualities of ‘strength, prowess, virility and endurance’ (Hagem, 1996: 73).

In reality, women have always watched and played sport, and for as long as there has been organised football in England, there have been female fans. Men may have thought the football match an unsuitable place for a lady – one male supporter wrote to the Leicester Mercury in 1889 that he would ‘have liked to take [his] wife and son to matches but that bad language makes it impossible’ (Murphy et al., 1990: 56) – but women did attend games. Reporter Charles Edwardes noted in 1892 that it was not just working-class men who had ‘football fever’, but many elderly people and women as well. He was surprised that ‘the fair sex’ were prepared to stand on the terraces, taking ‘their chance in the crush which often precedes entrance into the field: and, to do them justice, they do not seem to mind these crushes’ (Taylor, 1992: 7).

In 1884, a referee complained about the way he was treated by a group of disgruntled fans after a game, and his words make it plain that he was outraged not by their complaints, but by their sex and their contravening of their status in society as women and mothers: ‘After the affair was over I was tackled by a flock of infuriated beings in petticoats supposed to be women, who without doubt were in some cases mothers, if I may judge from the innocent babies suckling at their breasts. They brandished their umbrellas and shook their fists in my face’ (Taylor, 1992: 7).

The year after that, before the Football League began in 1888, Preston North End were forced to withdraw their offer of free entry to ladies when 2,000 women turned up at the ground (Taylor, 1992: 7). Rob Lewis (2009: 2167) points out that by 1948, over a third of women watched sport of some kind, mostly football, cricket or tennis, adding that some would be accompanied by male partners, but others were happy to attend alone and in their own right. When the Ladies Free concession was scrapped, women were frequently offered a reduced entry rate; by 1890, the minimum entry price charged in the Football League was 6d, with boys and women usually paying 3d (2169).

After World War One, when women entered the workplace in large numbers for the first time, women also began attending football matches in large numbers. The Leicester Mercury’s coverage of the local side’s game against Clapton in 1922 noted ‘a good sprinkling of women. Quite a number of women, in fact, faced the cup-tie crush without a male escort. If Leicester is any criterion, then the lure of the English Cup is rapidly infecting the female mind’. The Mercury’s report on the 1927 Cup final commented: ‘A remarkable feature was the number of women who had accompanied their husbands and sweethearts. Many mothers carried babies in their arms and confessed they had brought them to see the cup-tie’ (Murphy et al., 1990: 77–78). The City Corporation of Manchester provided special transport for the region’s women wishing to travel to games, while contemporary reports suggest that the crowd for the 1929 Cup final between Bolton Wanderers and Portsmouth was split equally between men and women, and local newspapers began to nickname Brentford ‘the ladies’ team’ due to the high number of women travelling around the country to watch them (77–78).

The idea of the ‘civilised’ English football fan grew during the 1920s, when more women took advantage of their war-induced freedom and went to sporting events. Murphy et al. (1990: 73) point out that football violence dipped between the two world wars, a time that allowed the establishment of the myth of the civilised English football supporter – and a time when more and more women went to games. The football ground at this time was a place suitable for ‘respectable’ people to go, both men and women.

Dunning et al. (1988) argue that prior to the 1966 World Cup in England, newspapers began to sensationalise their coverage of football, including focusing on crowd disturbances, in order to increase sales. This presented the football ground as a place where violence was commonplace, expected and even acceptable, thus attracting elements who sought a place to fight, making the concept of the ‘dangerous’ ground a self-fulfilling prophecy. They conclude that hooliganism at football reached an early peak in 1968, when the skinhead movement was at its height (17). The violent members of the football crowd began to organise themselves into ‘firms’ during the 1970s – gangs of hooligans fighting for a particular team. Anne Coddington (1997: 2) describes the popular perception of the football ground during the 1970s and 1980s as ‘a haven for racist, sexist thugs’, explaining that many women were put off going to football for fear of violence during this period. Yet this was not the case for everyone, and this is where this book intervenes.

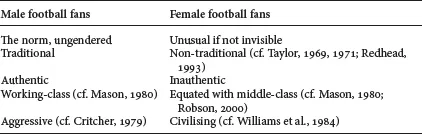

By researching female football supporters of different generations, I have sought to discover and understand their experiences. Historically, the mainstream of academic literature about football fandom has focused heavily on male experience. Male football fandom is the norm; men are entitled to go to football, and their fandom is an expression of their values – most typically working-class, community- or ‘tribe’-focused, with ritualistic displays, whether that is the chanting identified by Crawford (2004) or the aggression highlighted by Marsh et al. (1978).

However, female participation in football fandom has largely been marginalised or omitted entirely from studies. This is despite the acknowledgement in newer work that (male) football fandom has changed drastically since the mid-1980s, moving from an experience characterised as a working-class expression of masculinity to one characterised as more ‘commercial’ and ‘globalised’, as discussed by critics such as Richard Giulianotti, and as more ‘civilised’ and ‘gentrified’, that is, middle class, as discussed by critics such as Robson. Even when women’s presence or influence is acknowledged, as it is in the later work of Williams, Dunning and Murphy, it is assessed according to how they affect the behaviour and experience of men, with ‘women’ being positioned as different by default.

The collected historical body of knowledge about football fandom according to gender can be summarised thus:

However, some researchers have looked at how female fans demonstrate their football fandom; this includes Coddington, the only researcher that has examined the broader female experience of English football fandom in any depth. She set out her aims clearly in the subtitle to her book One of the Lads: Women Who Follow Football (1997), which targets both an academic and a non-academic audience in recounting the experiences of many women of different generations, supporting a wide range of teams from all over England.

After highlighting the invisibility of female fans in popular culture (she gave the example of J.B. Priestley’s The Good Companions, where she argued that football was portrayed as ‘an all-male world, an escape from ailing children and nagging wives’), Coddington – a journalist by trade – interviewed fans, footballers’ wives, female football administrators and female football writers and broadcasters, arguing that all female contributions to men’s football have been written out of the sport or at best marginalised.

Coddington’s (1997: 211) concluding chapter makes some suggestions as to how women can be encouraged to watch men’s football. She couches these ideas not simply as ways to promote gender equity, but also in furtherance of the abiding dictum that female presence will encourage better behaviour in men. Coddington also put the responsibility for targeting female fans squarely on football authorities, criticising their stances as ‘not good enough’ (213) and arguing that the traditional concept of football fans being ‘born, not made’ (215) may now be outdated.

Her work has been followed by some smaller-scale and more specific studies of particular elements of female fandom. John Harris (1999), in his study of the media coverage of the 1996 European Championships, did touch on the increasing popularity of football in the United Kingdom, and the concurrent rise in the number of women attending games; and Katharine Jones (2008) has more recently examined women’s gender identification and performance within football fandom. There have also bee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Background to the Research

- 3 The Female Fans Relationships within Her Family and Fan Community from Childhood to Adulthood

- 4 Some Patterns of Female Fans Supporting Performances and Behaviour

- 5 Female Fans Experience of the Significance of the Supporters Trust Movement

- 6 The Perception of Female Football Fans Practices by Clubs and Authorities

- 7 Looking to the Future

- Bibliography

- Index