On March 12, 2011, the day after the Great East Japan Earthquake of magnitude 9.0 struck the Sanriku coast encompassing three prefectures, Iwate , Miyagi , and Fukushima , one of the four reactors of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station melted down and exploded. This was followed by the meltdown of two more reactors on March 13 and March 14. While the earthquake and the tsunami took a total death toll of 15,894 in the whole region, approximately 1600 people died of exposure to heavy radiation and of related causes in Fukushima. Also, as many as 113,000 residents in Fukushima were evacuated and became displaced persons . The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) ranked this nuclear disaster as “Level 7: Major Accident” in the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES) . This is only the second case where the IAEA gave this highest level within the scale, along with the Chernobyl nuclear disaster , which had its 30-year anniversary on April 26, 2016.1

Human Victims of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster

Nevertheless, the Japanese government and the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) that administered the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station did not make public the nuclear meltdowns of the three reactors and kept denying the facts for two months, until May 2011. (To this day they have not told the whole truth). Meanwhile, on April 22, 2011, while concealing the inconvenient truth about the nuclear meltdowns from the public—including the residents of Fukushima—, the Japanese government abruptly expanded the evacuation zone to a 20-kilometer (12.5-mile) radius around the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station , from a 10-kilometer (6.25-mile) radius, and designated the area within the 20-kilometer radius to be a “warning zone ” (an “exclusion zone ” in effect and hereafter). The area beyond the 20-kilometer radius and within a 30-kilometer (18.75-mile) radius was designated as a “semi-warning zone .” Simultaneously, the Japanese government forcibly evacuated the residents who lived in the exclusion zone by bussing them to temporary shelters . They were not given time even to pack their belongings.2

Subsequently, TEPCO’s financial compensation (actually paid by the Japanese government because the company went bankrupt) to the evacuated residents was delayed and insufficient. The inadequate compensation also created a disparity between the residents who lived in the exclusion zone and those who lived in the area just outside the exclusion zone. The former, who were forced to evacuate, received monthly compensation of ¥100,000 (about US$833 calculated at the exchange rate as of March 31, 2011) from TEPCO. However, the compensation was hardly enough to make up for the loss of houses and livelihoods for the displaced evacuees. In contrast, the latter, who had remained and continued to live on the contaminated land, received no compensation. The anger and frustration of the residents—both within the exclusion zone and those outside of it—reached such an intolerable level that many of them filed lawsuits against TEPCO.3

Case of a Local Farmer

In February 2016, to mark the five-year anniversary of the nuclear disaster in Fukushima , a documentary film entitled, “Daichi o uketsugu” (Inheriting the Earth), was released. One of the residents of Fukushima, 40-year-old Tarukawa Kazuya , was featured in the documentary. He is an eighth-generation farmer in Sukagawa , about 40 miles west of ground zero. Earlier, Tarukawa quit his job and returned to his hometown to help his father on the farm. His father had taken pride in growing organic cabbages, using no pesticides. However, after the nuclear meltdowns , the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF) banned the produce in the locale from sale, but paid no compensation to the farmers there. When MAFF notified Tarukawa’s father that he could not ship 7500 cabbages that were about to be harvested, he hanged himself. After the death of his father, Tarukawa received a one-time payment as “consolation money” of ¥80,000 (about US$666) in 2011. He then received ¥40,000 (about US$333) in 2012. That was all.4

Tarukawa states:

TEPCO and the Japanese government neither provided financial compensation for the damage to my dad’s assets nor took measures to decontaminate his farmland. Nobody has taken responsibility even after five years have passed … It is not easy for me to appear in the film and to speak in TV and newspaper interviews. It is easier for me just to work on the farm. But, if I stop speaking out, my dad’s death will be meaningless and also the unconscionable truth of Fukushima will be forgotten. Therefore, I keep speaking.5

Tarukawa is one of 800 original plaintiffs in the

class-action lawsuit against TEPCO and the Japanese government called “Give Us Back Our Way of Living, Give Us Back Our Land of Living,” which was filed in March 2013. The number of plaintiffs had expanded to 4000 by May 2016.

6 Companion Animals in the Exclusion Zone

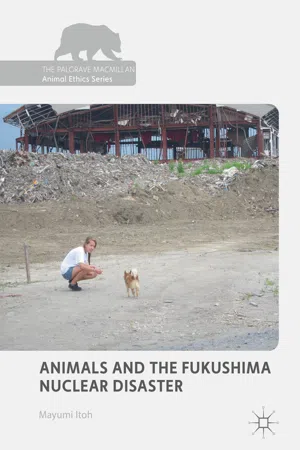

The case of Tarukawa Kazuya is only one example of the physical and psychological sufferings of the victims of the nuclear meltdowns of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station . Each of the 100,000 victims have their own physical and psychological pains to relate. In turn, it is estimated that about 25,000 companion animals were living in the exclusion zone before the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami : approximately 11,600 dogs and at least 13,400 cats. Nevertheless, the Japanese government forbade residents to take their companion animals with them when they were evacuated.7

Companion Animals in the TEPCO Employees’ Housing District

Strangely, there was one area in the exclusion zone where there were conspicuously no animals left behind. It was a stark contrast to the rest of the exclusion zone where all sorts of animals were left behind. This exceptional area was the residential quarters of the TEPCO employees of Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station . TEPCO had built a new housing facility for its employees, which looked too modern and out of place in the locale of the otherwise rural Futaba county . Curiously, there were no cats or dogs in this housing district, whereas all of the cats and dogs were left behind in the rest of the exclusion zone. TEPCO had obviously known about the nuclear meltdowns at the onset on March 12, 2011, and evacuated its employees’ families, as well as their companion animals, before the Japanese government issued the evacuation order to the residents in the exclusion zone.8

History repeats itself. About seven decades ago, in August 1945, in the Japanese occupied territory of Manchuria (currently China’s Northeast Region), the Japanese residents, as well as their companion animals, were left behind when the Soviet Army invaded Manchuria. The Japanese Kwantung Army had evacuated their own family members first, and then retreated from Manchuria, abandoning the Japanese civilians at large. Consequently, countless Japanese farmer-settlers were plundered and massacred by the Soviet Army . Takarada Akira (b. April 1934), the actor who played a lead role in the original Godzilla movie (1954), vividly recalls his childhood experiences in Manchuria, including witnessing Russian soldiers gang raping Japanese women. When his family were evacuated and headed to the Harbin station in order to catch a repatriation train, they were obliged to leave their family dog in the house. However, to his surprise, the dog followed them all the way to the train station. He wanted to take the dog with him on the train, but it was not allowed. Takarada cannot forget the face of the dog at the station to this day.9

Livestock Animals in the Exclusion Zone

In addition to the companion animals, many livestock animals were raised in the exclusion zone—3500 head of cattle, 30,000 pigs, and 630,000 chickens—and the region’s beef and dairy industries were ...