1.1 Citizens and Their Feelings Toward Political Institutions: A Crucial Bond

Public opinion is one of the main subjects of study in many disciplines of social sciences. In political science, it relates to the connection between citizens and the fundamental elements of politics, such as institutions, parties, policies, and so on. This is particularly crucial in democratic systems, where citizens (demos, the people) are the engine of the political system and legitimize its structures and actions. Despite the limits of public opinion studies in terms of gathering data, quality of information, and measurement error (Saris and Sniderman 2004), the people’s voice remains a cornerstone of democracy.

Political scientists, in analyzing different typologies of government, have theorized several concepts of the relationships between people and the political system that they live in. During the last century, different authors have suggested concepts such as legitimacy, trust, loyalty, political efficacy, and support to study (both theoretically and empirically) feelings, attitudes, and values toward politics. They have different degrees of similarity and variance, although academics agree on the fact that those feelings are crucial in ensuring the existence of democracy; if we agree with the argument that “democracy is universally understood as a form of government involving ‘rule by the people’,” (Dahl 2001, p. 3405) we should admit that the way people perceive and consider the democratic political system is very important for its maintenance and change.

The importance of this topic in social sciences explains why the institutional and political evolution of the European Union has been a rich source for studies on this matter. The progressive steps through European integration incited analysts worldwide to examine feelings toward the first supranational “creature” 1 of the contemporary era.

How do Europeans perceive the EU? Do they agree with the steps toward integration? How do they judge EU policies? Does a “European sense of belonging” exist? What are the origins of those attitudes? These questions (and more) continue to challenge social scientists and represent the main focus of this book.

1.2 Defining Attitudes Toward Europe

Before attempting to describe or explain citizens’ attitudes toward Europe and their origins, it is crucial that citizens’ opinions are properly conceptualized and operationalized. A large part of the literature over the last two decades has focused on the concepts of consensus and Euroscepticism. After the Maastricht Treaty, Euroscepticism became really popular in studies about political parties and public opinion, it also spread across disciplines and into the media.

Before Maastricht, scholars basically agreed on the idea of citizens’ “permissive consensus” (Eichenberg and Dalton

1993; Hooghe and Marks

2009; Inglehart

1970; Lindberg and Scheingold

1970; Moravcsik

1991) toward European integration and observed a sort of “passive” safe-conduct toward national political elites in the creation of the European Political system. According to this perspective, European integration was basically an international process created by national elites (governments) and approved (or not opposed) by their citizens. Down and Wilson (

2008), among others, empirically showed the magnitude of change in European public opinion before and after Maastricht. They concluded that “post-Maastricht we have indeed moved into a world in which there is more significant public disagreement than that prevailed pre-Maastricht,” (p. 46) but “this is not simply a function of a decline in support for the EU.” (p. 46) As the authors pointed out, although we can define two different trends toward Europe (pre- and post-Maastricht), it does not mean that European citizens started to oppose the EU institutional project: “Yet, viewed over the long run, the change that has occurred is quite limited.” (Down and Wilson

2008, p. 46) However, it is possible to say that feelings of “Constraining Dissensus” (Hooghe and Marks

2009) started to grow. In other words, a critical approach to Europe and its policies emerged once the importance of the EU started to impact citizens’ lives: “elite decision making would eventually give way to a process of politicization in which European issues would engage the mass public.” (Hooghe and Marks

2009, p. 6) Usherwood and Startin (

2013) identify four main changes introduced by the Maastricht Treaty that may explain this change of direction. First of all Maastricht marked “the creation of a new political order,” (p. 3) blurring the division between national and supranational competences; second, it opened a real debate about the basis of the EU; and third, since Maastricht, the citizens of some member states have, on several occasions, been called on to participate actively in EU integration (by voting in referenda). After the Treaty, parties started to inspire a sense of skepticism toward EU integration. The different levels of support for the European Union before and after Maastricht have been extensively analyzed by Down and Wilson (

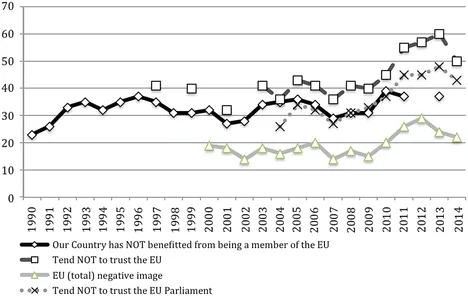

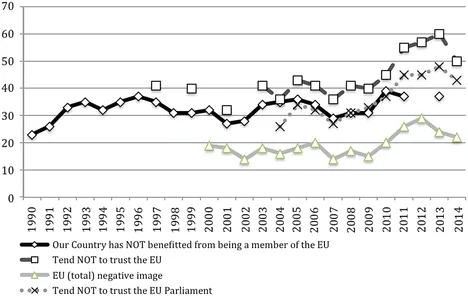

2008), both for each member state and for the EU as whole. However, during the 1990s and 2000s opposition to the EU did not change dramatically, except during the years of the financial and economic crisis. As Fig.

1.1 shows, negative attitudes toward Europe increased in 2010, with the percentage of people distrusting the EU increasing by about 15 percentage points from 2009 to 2011. While negative image and distrust toward the EU Parliament grew respectively by 11 and 12 percentage points during the same period. The trend of support/opposition toward Europe does not show any specific tendency, but it does show periods of shock due to particular causes (such as the Maastricht Treaty or the economic crisis), during which opposition increases. The data on attitudes toward the EU collected during the recent crisis strongly supports this view (see Di Mauro and Fraile

2011).

The nature and number of changes since the early 1990s are still being debated and will be a crucial topic of discussion in the future. All in all, a clear countertrend has emerged in Europeans’ perceptions of EU institutions, a sentiment defined by the popular term “Euroscepticism.” (Taggart 1998)

Euroscepticism was originally created to define the opposition of political parties toward the European integration process. Over a couple of decades it also became quite popular in public opinion studies, summarizing every sentiment, act, declaration, and proposal opposing European integration. This phenomenon became evident when many authors started to describe the gap between citizens and European elites (see Karp et al. 2003; Rohrschneider 2002) and talked about an EU “democratic deficit.”

Euroscepticism, in the last decades, has raised many questions, particularly: Could Euroscepticism include all citizens’ attitudes toward European institutions and the integration project? Is it able to describe those attitudes at any stage of EU institutional integration?

A decade after Taggart’s definition, some scholars started to note that, although the concept of Euroscepticism acquired wide popularity it also contributed, both theoretically and empirically, to the indeterminacy of the conceptualization of attitudes toward the EU. First of all, the term is inconsistent with the growing saliency and impact of European institutions in their citizens’ lives (see Hooghe and Marks 2009). The term skepticism indicates a negative attitude to a distant/ongoing process. It can indicate the negative odds that a process will end in a certain way (for example “I do not think that European integration will end with a federal European State, or that it will include some more member states”) and/or a negative perspective on that process (for example “I do not believe that this is the right way to integrate European states, or that integration is a good thing, etc.”). The dynamic element of skeptical attitudes implies a gap between citizens and political institutions. This gap should be considered in terms of a certain area and time frame. In the first case skepticism should refer to citizens who are far from the institutions and/or are not under their jurisdiction, for instance, “non-Europeans are skeptical about the EU.” In the second case, citizens are skeptical about the “conclusion” (or even partial results) of the (integration) process. Overall, skepticism implies distances that have been strongly reduced by European integration.

The European Union is strongly characterized by an evolving process regarding its membership, rules, and roles. In the last 20 years EU membership has almost doubled. A great number of policies, once considered pertinent exclusively to states, became strongly Europeanized; while EU in...