eBook - ePub

Scenes, Semiotics and The New Real

Exploring the Value of Originality and Difference

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides a semiotic analysis of 'scenes', powerful vehicles for introducing new ideas, perspectives and behaviours, as a concept. In particular, it examines the types of scene that exist; explores their effectiveness in spreading new ideas; and considers their vital role in introducing originality and difference in modern society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Scenes, Semiotics and The New Real by Chris Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Criticism Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Defining Scenes

Abstract: This chapter begins with a definition of what scenes are, as well as highlighting some of their salient, defining characteristics. Also provided is a matrix of scenic ‘types’, which organizes instances of scenes according to whether they are predominantly based in a given location, in a definable period of time or some combination of both. This typology provides three broad categories of scenes, which are then explored in Chapter 2 and 3. Finally an example of a proto-scene is provided. Examining this example is important because not only does it highlight when a ‘scene’ isn’t actually a scene, but it also outlines the factors that can prevent proto-scenes fully developing into scenes-proper.

Keywords: anti-austerity; Greece; matrix of scenes; proto-scenes; scenes; scenic types; Tsipras

Brown, Chris. Scenes, Semiotics and The New Real: Exploring the Value of Originality and Difference. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. DOI: 10.1057/9781137591128.0005.

What connects a successful London Borough to a local market in Modena (Italy), via new approaches to criminal justice and big wave surfing? The answer I’m suggesting is that they all have a number of attributes in common that not only results in them being attractive and different but also powerful vehicles for introducing new ideas, perspectives and behaviours. To begin to unpack these ideas I use this chapter to start exploring the idea of scenes. Beginning with a broad definition and an outline of their main characteristics, I then provide a typology of scenes that seem to be most predominant. I finish by examining a ‘proto’-scene that never came to fruition: Greece’s anti-austerity movement – a backlash by the Greek people against a failed economic policy that has led to massive unemployment and huge levels of debt and that has left the country mired in recession. That this almost-scene began with promise but failed to establish itself therefore provides a useful counter-position when thinking about why those scenes that are scenes (see Chapter 2 and 3) managed to achieve their success.

So, what is a scene?

Starting with a definition of what a scene is, I regard these as situations in which people are doing something different from the norm. By norm I mean the average day-to-day experiences one generally encounters: for instance, the conversations we usually have, the genres of music we generally find ourselves listening to, the variety or type of restaurants available for us to eat in and so on. The idea of ‘situation’, meanwhile, can and should be interpreted broadly. For instance, a situation could occur entirely in one place, but it could also represent activity undertaken by many people in many places. Situations might also be taken to encompass less corporeal attributes such as the development of a coherent set of beliefs that offer up different takes on life. Importantly, however, no matter what the situation, the break from the norm offered up by the scene will be something that presents new perspectives. Taking just two examples: London’s 1970s punk-rock music scene can be seen as an angry reaction to social alienation in a post-industrial Britain in economic decline. In terms of art, Malevich’s ‘suprematism’ movement was born of the idea that all art is just an imitation of nature and for it to be original it must eschew any form of replication. The result was Malevich’s groundbreaking painting of a black square on canvas (Black Square, 1915), designed to privilege the invoking of emotion over visual phenomenon. Scenes therefore serve to enrich our lives by (for instance) providing new genres for us to explore, new perspectives through which we can understand or even (as in the case of Tofino, the scenes described in the preface) new activities and lifestyles for us to engage in.

As I will show through the examples I provide in Chapter 2 and 3, scenes will typically share a number of common characteristics:

Although this outline of what scenes are perhaps sounds a tad grandiose, scenes do not have to be: speaking to the owners of my favourite coffee shop, for example, they describe how they wanted to create in Crouch End (north London), the type of atmosphere they experienced in relation to the (fika) coffee scene in Gothenburg – here then an initial attempt at difference is established by the owners but is subsequently enhanced and perpetuated by the customers and staff, and will remain in place until someone or something serves to shift it. Scenes then can be either grand or small scale (they can represent both punk music and a simple shop), but what they do have to be is identifiable: you immediately know when you encounter or arrive at one. Clearly, though, scenes can only be scenes when they stand in contrast to the norm: as soon as they become mainstream, they lose their distinctiveness and so can no longer be distinguished from the day to day that surrounds us (as an example, once every restaurant specializes in ‘street food’, which they now all seem to do in north London, the idea of street food loses its ability to signify difference).

Types of scenes

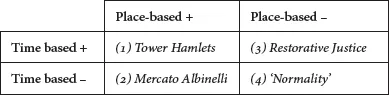

Generally, we come across instances of scenes (situations) in many areas of social life but in all cases, scenes will possess qualities that are, to a greater or lesser extent, related to time and place. As such, scenes can be predominantly time-based, predominantly place-based or represent a combination of the two. This affords the possibility (along with a situation of ‘normality’) of three potential scenic types; these are detailed in Figure 1.1, labelled by the examples I use here as I explore them in Chapter 2 and 3.

FIGURE 1.1 A typology of scenes

Proto-scenes

Before I move on to examine these examples in more detail however, I begin my analysis by looking at a recent example of a ‘proto’-scene – a nearly scene which, it was hoped, would flourish into a new movement, but where the efforts of its progenitors ultimately ended in failure. The analysis is useful because it highlights the difficulties in creating scenes and also because it creates a negative case – something against which we can compare actual instances of scenic activity and so see what is required to establish a scene, whilst simultaneously enabling comparisons with the factors that can lead to scenic ‘still-birth’. The proto-scene in question is the Greek anti-austerity movement.

Oxi!

The final result of the Greek referendum of 5 July 2015 overwhelmingly pointed in one direction: with 61 per cent of the population choosing oxi (‘no’), the people had decided against further austerity, even if this meant Greece leaving the Euro and possibly even the European Union. In many ways the vote marked Greece’s continued march towards becoming Europe’s first anti-austerity scene, a process that had really gained momentum some five months earlier with the election of Alex Tsipras and the left-wing Syriza party. The notion of ‘anti-austerity’ has its origins in the 2008 financial crisis, which left Greece in substantial debt as it borrowed to keep its banks from collapsing, whilst also coping with rising welfare bills and falling tax revenue. At the same time, interest rates had surged as investors began to worry about eurozone governments defaulting on their debts, with this rise in the cost of borrowing serving to push Greece’s debts higher and higher.

As might be expected, Greece moved into recession, but the decline in Greece’s economic performance was exacerbated by the reaction to the fall-out from the crisis from within the eurozone. In particular, rather than encourage countries like Greece to pursue a Keynesian economic approach, which would have involved its government spending its way back to growth, the eurogroup required Greece to return to a healthy economic status by immediately reducing its debts (the assumption underlying this novel approach to economic policy being that such fiscal discipline provides a certain level of assurance to investors). The push for immediate austerity however only and unsurprisingly served to worsen Greece’s situation. But because it was accompanied by a discourse of blame, eurozone governments were able to gloss over the economic maltreatment they were dishing out. For instance, the ‘code’ promoted by the dominant eurozone members was that Greeks were ‘lazy’ (in the sense of not conforming to the ‘protestant work ethic’1); that they avoided tax; and that only economic pain and radical changes to the operation of government and to the competitiveness of the labour market could alleviate this. In other words, until the Greeks learned how to reform they should be left to suffer.

The Greeks did as they were told and between 2009 and 2010 Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou announced three programmes of tough public spending cuts. But a downward economic spiral ensued and fears of a possible default on its debts led to eurozone countries offering Greece a £91 bn/€110 bn rescue package.2 The price of rescue, however, was the requirement that Greece impose even more stringent austerity measures, which served to exacerbate the already dour economic situation. This meant that a further loan of €130 bn was required just two years later. Incredibly this again was in return for austerity and so cuts to spending. As Ian Parker of the New Yorker magazine noted of the loan3:

That bailout, and a subsequent additional loan of a hundred and thirty billion euros, came with three kinds of obligation: Greece needed to privatize state assets, such as Athens’s port; reform institutions and practices perceived to be inefficient, including its health-care and welfare systems, in ways ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Defining Scenes

- 2 Tower Hamlets as a Type 1 (Time+/Place+) Scene

- 3 Further Scenic Types

- 4 Scenic Capital and the Attractiveness of Scenes

- 5 How Scenes Can Rapidly Diminish to Normality Part 1, Chainification

- 6 Simulacra and the Really Real (Authenticity)

- 7 How Scenes Can Rapidly Diminish to Normality Part 2, Tourism, Social Media and the Mass Media

- 8 Keeping a Scene, a Scene

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index