This introductory chapter provides background information on the history and society of the Danish West Indies from the 1620s to 1878 to coincide with the period of Indian indenture in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Some general information will be on the overall Danish West Indies, but the main focus will be on St. Croix, to which East Indians were brought to labor on the estates/plantations. The purpose of this information is to provide a general knowledge of the Danish West Indies so that the indenture experiences of East Indians can be contextualized with other events sweeping through the islands at that time. This chapter provides a general background of East Indian indenture in the Caribbean, which has received enormous academic attention. Finally, the methodology, the aim, the purpose, and the focus of the book are explained in the second half of the chapter.

Historical and Social Context of Danish West Indies up to 1878: History and Society

The Danish West Indies is made up of three small islands (St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John) in the Northern Caribbean, 40 miles east of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. These islands are located in the Lesser Antilles in the Leeward island chain. The total area of all three islands is about 132 square miles. St. Croix is the largest, 20 miles long and seven miles wide, while St. Thomas is 13 miles long and three miles wide. St. John is nine miles long and five miles wide. St. Thomas is largely infertile and mountainous but has an excellent harbor. St. Croix is generally flat and the clay soil is more suitable for plantation agriculture. St. John is mainly forested.

The Spaniards claimed these islands in the early sixteenth century but ignored them because they were thought to be relatively dry, lacked precious metals, and were inhabited by fierce Caribs. By the 1600s, however, other Europeans—mostly privateers, pirates, and smugglers—used these islands as a base to launch attacks on the Spanish Caribbean and Spanish Latin America. The Danish West Indies remained a pirate base for a number of years and served as a depot (station) for European traders carrying goods (slaves included) from Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean. By the 1620s, St. Croix and St. John attracted attention from a few hundred British, French, and Dutch sugar planters. The development of sugar plantations proved futile, however, because of intercolonial European Caribbean warfare (see Figueredo 1978). After a series of failed colonization attempts by various European nationalities in the latter part of the seventeenth century, St. Thomas and St. John were under control of the Danish West India Company. Denmark eventually bought St. Croix from the French in 1733, placing all three islands in the ownership of the Danes. Unlike other European powers in the Caribbean, the Danes allowed all European nationalities to colonize the Virgin Islands. Actually, from 1773 to 1917, Danish nationality in the Danish West Indies was a minority population. The reason for this unusual colonial situation was that the Danes experienced high levels of deaths and therefore non-Danish nationals were encouraged to settle and colonize the Danish West Indies through various tax incentive schemes (Boyer 2012). The result was a multiplicity of European nationalities in the Danish West Indies: Dutch, French, Swedish, Danish, British, Portuguese, German, Norwegian and Brazilian. English was the language of the government, while the Africans spoke a Dutch Creole called Negerhollands (see Highfield 2009).

The absence of native people and the failed immigration scheme with Europeans to provide the labor on the plantations caused the Danes and European nationalities to turn to Africa—like their European counterparts elsewhere in the Caribbean. Between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an estimated 53,000–57,000 African slaves were brought to the Danish West Indies to work on the sugar plantations through the infamous African Slave Trade. No less than 30 % of slaves perished on the Middle Passage. Conditions on the sugar plantations were unbearable. They were housed in subhuman dwellings and worked on the plantations from sunset to sundown with inadequate rations and medical care. Thousands died from overwork, malnutrition, disease, stress, and stern treatment. Charles Taylor (1888: 205) wrote that slaves were “liable at the slightest provocation to be whipped or tortured—sold away to Porto Rico—to lose their life or a leg for stealing, or to be broken on the wheel.” Some Africans resisted slavery through flight and formed independent enclaves such as Maroonberg on the east end of St. Croix. Some slaves challenged their masters directly. In 1733, slaves revolted against their masters on St. John and held the island for six months after which they were finally defeated by European authorities. The revolutionaries were severely punished, including public executions. Finally, African slaves defeated their masters through a rebellion on St. Croix and gained freedom in 1848. Except for the Haitian Revolution of 1804, the Danish West Indies, particularly St. Croix, is the only other Caribbean island where slaves gained outright freedom through direct insurrection.

During slavery, Africans contributed immensely to the development and transformation of the Danish West Indies. They single-handedly, through back breaking labor, transformed these sleepy forested islands into large tracts of productive plantations/estates, making St. Croix in particular the most profitable island in the eighteenth century. Sugar made up more than 80 % of the total value of goods exported from the Danish Caribbean to Denmark (see Westergaard 1917). The arrival of Africans also brought about a profound demographic and sociological change in the Danish West Indies. Blacks surpassed whites as the numerically dominant racial group but wielded no significant power in the plantation system. By 1835, 1892 whites and 19,876 slaves lived on St. Croix, 3520 whites and 5298 slaves lived on St. Thomas, and 344 whites and 1929 slaves lived on St. John. The racial imbalance created the social hierarchy of a slave society in the Virgin Islands, with whites, free coloreds, free blacks, and enslaved blacks occupying the higher, middle, and lower classes, respectively (Roopnarine 2010b: 92–94).

There were some other noticeable patterns soon after emancipation. Firstly, the newly freed Africans continued their struggle for better living and working conditions since the residues of slavery were still around. Some Africans stayed on the plantations, while others left the plantations permanently. Meanwhile, the planters continued their stranglehold on labor by introducing and imposing a host of new regulations that effectively transferred post-emancipation labor relations into their hands. The Africans saw this as an attempt by the planters to bring them back into slavery (see Jarvis 1945). Tensions reached a boiling point, and in 1878, the working class Africans rebelled (Fireburn) against the powerful post-emancipation planter class and burned down a number of plantations and Frederiksted, one main town on St. Croix. Secondly, plantation/estate lands were parceled out into small holdings, although this occurred more in St. Thomas and St. John. On St. Croix, the plantations were either phased out completely like in the mostly dry west end of the island, or were centralized and supported with new technology. Either way, the pendulum of power never swung too far away from the planter class. The planters influenced the direction of labor through their representation in the Colonial Council, the local governing body in the Danish West Indies. Thirdly, the Danish West Indies, particularly St. Thomas, experienced a degree of urbanization as well as out-migration from the estates and from the islands. Sugar cane cultivation was eventually phased out on St. Thomas and St. John and received a death blow with the introduction of European beet sugar in the world market in the early 1880s. Danish West Indian sugar could no longer compete with the cheaper and more preferred beet sugar. Lastly, the general description of St. Croix soon after emancipation was one of continued tension between the working class and the planters, precipitated by the abolition of the African Slave Trade and then slavery. The consequence was a continuous economic decline of the Danish West Indies, although it was more noticeable on St. Thomas and St. John than on St. Croix. Generally speaking, Danish West Indian society revealed feudalistic features, with firm boundaries between the planter and the mainly black laboring class. The Danish West Indies was essentially a caste society with firm boundaries where individuals remained more or less to the stations of life they were born into until death. Central to this plantation system was the abuse of the laboring force that was intended to maximize profits and retain the status quo. Such was the legacy of the Danish West Indian colonialism in which the echoing words were power and profit.

Methodology and Challenges

The book is based on my research on Caribbean indentured experience over the past 20 years, particularly on labor migration and resistance. Specifically, I lived and worked on St. Croix from 2002 to 2012 and therefore was able to access sources from the Whim Museum and the University of the Virgin Islands. I also conducted research at the National Archives in Washington, DC, on files relating to the United States Virgin Islands. I also visited former plantation sites of indentured Indians on St. Croix. Although some statistics are provided, the book is based on qualitative analysis using archival and nontraditional sources such as oral tradition. One chapter is dedicated to views and voices of indenture from about five participants from various backgrounds on St. Croix. One major challenge, however, is how one recovers or reconstructs the indentured narrative and the memory of indentured people when Indians are no longer around—not even any traces of them, I tackle this challenge by using the archival and oral history approach. First, I am fortunate to have the original list of the passengers who arrived in 1863. From this list I can draw conclusions about their gender, caste, age, and so on. I theorize what and how indentured Indians might have thought and felt, and I compare the St. Croix indenture experiment with other experiments in the Caribbean at that time. I argue that this technique is useful in recovering the past since history is not merely a record of significant events of the past. The concerns and questions in this study are: (1) Why were Indians brought to St. Croix? (2) How were they recruited? (3) What were their experiences in the holding depot and on the sea voyage? (4) Where were they distributed on St. Croix? (5) How was their plantation experience? (6) Was their plantation experience different from other indentured servants in the Caribbean? (7) Why did indenture collapse on St. Croix but continue elsewhere in the Caribbean? Full answers to these concerns and questions might not be possible, but attempts will be made to analyze and answer most of them.

Background of Indian Indenture in the Caribbean

The story of Indian indenture in the Caribbean (except St. Croix) has received enormous academic attention in a multitude of publications. The purpose here is to provide a general overview. Readers interested in a more in-depth analysis are referred to my prior book,

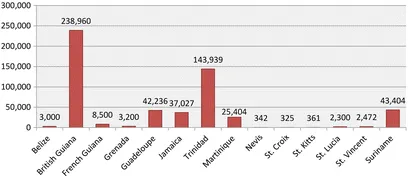

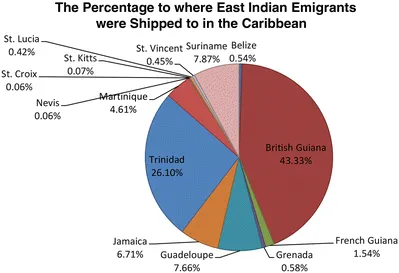

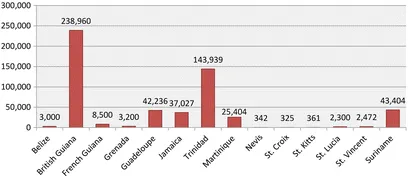

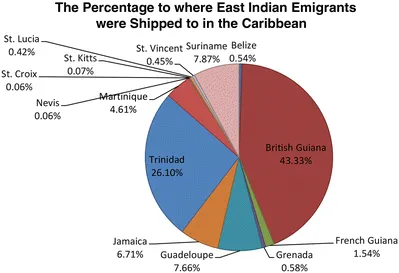

Indo-Caribbean Indenture: Resistance and Accommodation (2007). For about 80 years (1838–1917), the British, Danish, Dutch, and French governments brought about 500,000 indentured Indians from India to the Caribbean (see below). The arrival of these individuals was in response to (1) a labor shortage brought about because of the gradual withdrawal of Africans from plantation labor following slave abolition in various time periods in the mid-nineteenth century; and (2) the unsatisfying results of indentured labor from Europe, Africa, Java, Portugal, Madeira, China, and within the Caribbean. Of the 500,000 indentured Indians brought to the Caribbean region, an estimated 175,000 returned to their homeland when their contracts expired, while another 50,000 of those persons remigrated to the Caribbean for the second and even the third time. The following charts show the number and percentage of Indians brought to the Caribbean. British Guiana and Trinidad received the bulk of the emigrants (Fig.

1.1).

Organization of Indian Indenture

When Indian indenture began in British Guiana in 1838, there was never any formal organization of the system other than the involvement of private individuals and private companies. The reason for this private endeavor was that indenture was already privately practiced in a satisfactorily standard manner in Mauritius and other islands in the Indian Ocean, places which had also experienced slave emancipation and a subsequent labor shortage. From 1834 to 1837, at least 7000 Indians were shipped from Calcutta, India, to Mauritius to work as indentured laborers (British Parliamentary Papers (hereafter B.P.P) 1874: 2). This movement caught the attention of Caribbean planters who then negotiated with private firms for indentured laborers for their sugar plantations. The first shipload of 396 indentured Indians eventually arrived in British Guiana in 1838. These indentured Indians were severely abused by their plantation overlords. Ninety-nine of them died within the first two years of indenture (see Scoble 1840). The British Government subsequently suspended Indian indentured emigration to British Guiana. However, indenture resumed in 1845 but was suspended in 1848 because of financial difficulties. Indian indenture resumed in 1851 and continued until 1917, when it was uniformly abolished across the world (Roopnarine 2008: 208).

From 1854, the British government moved the private organization of indenture from a private practice to a state-controlled one. Indian indenture was organized and regulated by a three-way collaboration and interaction between the British Colonial Office, the Indian government, and respective Caribbean colonial governments (Look Lai 1993: 57). The purpose of the three-way collaboration was to prevent malpractice in the recruitment process, to avoid deaths on the sea voyage, to protect Indians from abuses in the Caribbean, and to discharge repatriation obligations. These obligations were often not met, and the main challenge was the powerful capitalist economy, which operated on material rather than human values. The administrators of the indenture system were merely interested in dividends and not in the general welfare or protection of those who came under their sway. Power and responsibility was distinctly disconnected (Roopnarine 2007: 33). Moreover, the Indian government was too weak to ensure a proper functioning of the indenture system because of its subordinate position within the colonial indenture system. To be sure, the Indian government was interested in protecting its citizens from exploitation and favored myriad legislation to achieve these goals. However, when pressured, the Indian government adopted a neutral policy of overseeing the fair commercial transaction of Indian emigrants but was reluctant about getting mixed up in any bargains (see Cumpston 1956; Mangru 1987). The Indian government was too distant from the day-to-day experience of indentured Indians and placed instead the responsibilities on the Protectors of Immigrants to ensure that Indian rights were not violated. The problem, however, was that these individuals shared more interests with the planter class than with the individuals they were supposed to protect. Additionally, the appointed Protectors of Immigrants generally did not fully understand the languages and customs of Indian indentured laborers, even with the support of interpreters (B.P.P. 1874: 24).

The British Government’s Reluctance to Allow Indian Indenture in Non-British Territories

Within the context of an unmanageable system, the British and the colonized Indian governments were reluctant to allow other European powers to recruit Indians to labor in foreign colonies. The governments were aware of defects in the indenture system but allowed the system to operate within the limits of British Caribbean co...