This chapter links the literature on political corruption with that on valence issues. It will discuss how the former literature has generally sought to understand the consequences of political corruption, as well as the reasons for its diffusion in different countries, while discarding (with few exceptions) the factors that could explain why political actors may have an incentive to campaign (in a stronger or weaker way) on political corruption issues. By doing so, the possibility of investigating the outcomes of the choice to ‘invest in corruption’ is precluded. I will argue that looking at political corruption using the framework provided by the valence issues literature helps fill this gap.

In this regard, I will present the different interpretation of the concept of valence issues first introduced into the literature by Stokes’s seminal article (1963), focusing in particular on the distinction between non-positional policy -based valence issues (e.g. issues such as reducing crime or increasing economic growth) and non-policy-based ones (e.g. credibility, integrity) (Clark 2014). In contrast to positional policy issues, which involve a clear conflict of interest among groups of electors (being in favour of or against the welfare state, gay marriage, and so on), when dealing with either policy or non-policy valence issues, voters hold identical positions (preferring more to less or less to more, depending on the issue). Corruption (honesty) is a typical example of a non-policy valence issue.

I will then highlight how the aforementioned types of valence issues, together with positional policy issues, can be viewed and analysed within a common theoretical framework that differentiates the possible campaigning moves available to political actors (candidates and/or parties) according to two simple criteria.

This latter point leads directly to the connection between political corruption and valence issues that will be theoretically and empirically investigated in the following chapters. To anticipate an aspect thoroughly discussed below, if political corruption is treated as a valence issue, it becomes possible to focus on how parties’ relative ideological positions and electoral considerations affect their emphasis on campaigning on corruption.

1.1 The Growing Interest in Corruption

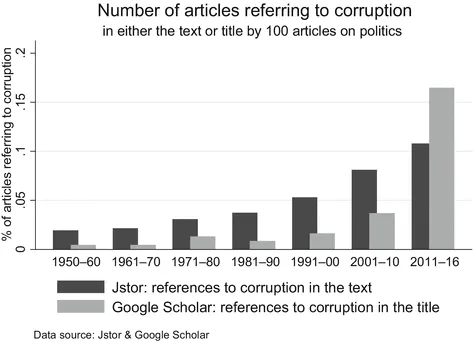

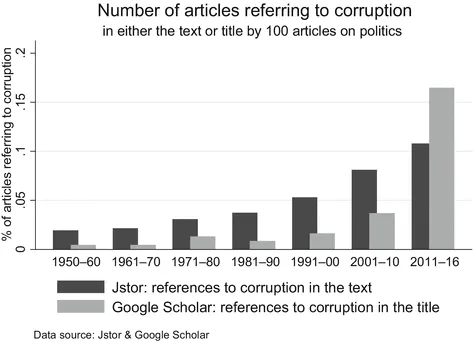

Since the mid-1990s, from leading international organizations, such as the EU and OECD, to international media and individual governments, the topic of corruption has become almost ubiquitous in policy circles. The debate on corruption has not taken place only in the public domain, however, because also academic attention to it has grown considerably over the years. This becomes apparent on conducting a simple

bibliometric check. The scores reported in Fig.

1.1 are based, respectively, on a Google Scholar and a Jstor search query. The number of books and articles referring to corruption among all political science publications grown linearly over time, rising from 2% in the 1950s to 10.8% in the past 5 years (source: Jstor).

1 The same significant growth is found when focusing on the proportion of books and articles with the word ‘corruption’ in their title among all publications on politics: from 0.5% in the 1950s to 15% once again in the last 5 years (source Google Scholar).

2 This growing interest is not surprising: corruption directly impacts on such important matters as fairness in the institutional and economic process, political accountability, responsiveness, etc. According to well-known definitions, corruption is ‘the misuse of public office for private gains’ (Treisman 2000: 399) or, also, ‘an act by (or with acquiescence of) a public official’ that violates legal or social norms for private or particularist gain (Gerring and Thacker 2004: 300). In both definitions, public officials are the main actors, while the extent and type of corruption are not specified (Ecker et al. 2016). Moreover, political elites may be held accountable not just for their own abuse of power and money but also for failing to limit corrupt behaviour in general (Tavits 2007).

Della Porta and Vannucci’s (1997: 231–232) definition of corruption centres on another recurrent theme in the literature: the breach of a principal-agent relationship. For Della Porta and Vannucci, political corruption involves a secret violation of a contract that, implicitly or explicitly, delegates responsibility and the exercise of discretionary power to an agent (i.e. the politicians) who, against the interests or preferences of the principal (i.e. the citizens), acts in favour of a third party, from which it receives a reward.

The literature on corruption has mainly focused on two sub-topics. The first concerns the consequences of corruption. A wide-ranging and multi-disciplinary literature has shown that contexts which suffer from higher levels of corruption are associated with, for example, poorer health (Holmberg and Rothstein 2012) and environmental outcomes (Welsch 2004), lower economic development (Mauro 1995; Shleifer and Vishny 1993), and greater income inequality (Gupta et al. 2002). Moreover, it has also been underlined that corruption is a problem that plagues both developing and more economically developed regions such as Europe (Charron et al. 2014).

The political consequences of corruption have also been well-documented. Corruption undermines legitimacy in a variety of institutional settings (Mishler and Rose 2001; Seligson 2002). In particular, corruption destabilizes the democratic rules by favouring some groups—especially the wealthy—over others (Engler 2016; Anderson and Tverdova 2003), thereby generating mistrust between the majority of citizens and their political leaders. Similarly, Rothstein and Uslaner (2005) have shown that corruption exacerbates social inequality, which in turn reduces people’s social trust, while Kostadinova (2012) found that corruption lowers trust not only in the government and public administration but also in parliament and political parties in general. Widespread corruption also depresses electoral turnout, because high levels of perceived corruption lead to more negative evaluations of political authorities and the political system in general (Anderson and Tverdova 2003; McCann and Dominguez 1998). 3

Finally, corruption has a possible impact on the vote-choice of citizens. According to democratic theory, one key mechanism through which citizens can combat corrupt elite behaviour is electoral choice. Given pervasive corruption among incumbents, or if a corruption scandal breaks prior to an election, voters who understand the costs of corruption should turn against the government in favour of a cleaner challenger and ‘throw the rascals out’ (Charron and Bågenholm 2016). In this respect, recent findings demonstrate that if corruption is perceived to be high, the electoral support for governing parties decreases (Klašnja et al. 2016; Krause and Méndez 2009). Similarly, several studies have found that the electorate actually punishes politicians and parties involved in corruption scandals (Clark 2009), while corruption allegations appear to harm the electoral prospects of the accused politicians (Peters and Welch 1980; Ferraz and Finan 2008). However, there is no lack of exceptions to this rule, since many voters still remain loyal to their preferred parties. For example, recent empirical studies have shown that the accountability mechanisms are less decisive in their impact, because corrupt officials in many cases are re-elected or punished only marginally by voters (Chang et al. 2010; Reed 1999; Bågenholm 2013). This may be because at least some voters personally benefit from the corrupt activities, for example in the form of clientelism (Fernández-Vázquez et al. 2016; Manzetti and Wilson 2007), or because citizens have strong loyalties to certain politicians or parties, so that a corruption scandal is not enough to change their voting behaviour (de Sousa and Moriconi 2013). Moreover, what really matters in some instances is not how corrupt a given party is perceived to be, but whether it is deemed to be more corrupt than the other parties (Cordero and Blais 2017).

Because the corruption issue is so important for its economic and political consequences, it is no surprise that understanding the causes of the phenomenon has garnered a great deal of recent scholarly attention as well. Most analyses of the causes of corruption start from the presumption that the abuse of public office for private gain stems from voters’ inability to rein in their representatives. In the face of government malfeasance, scholars ask whether and how political institutions (but also political culture and the level of economic development: see Lipset and Lenz 2000; Montinola and Jackman 2002) affect it. Answers in the literature generally agree that corruption is lowest where political institutions give voters the ability to punish politicians who fail to perform according to expectations. In regard to the already-discussed principal-agent perspective, researchers often highlight the role and the importance of political competition (Alt and Lassen 2003) as measured through the existence of partisan and institutional checks in limiting agents’ (i.e. politicians’) discretion to act on their own behalf. However, given that with no reliable information about whom to check and when, the ability to keep agents in check (and thereby avoid a moral hazard problem) is hugely hampered; good government requires also that those who would like to see corruption punished are in a position to observe, report, or block undesirable behaviour (Brown et al. 2011). These elements—effective monitoring and institutional checks—are in fact fundamental to well-designed principal-agent relationships (Heller et al. 2016).

Montinola and Jackman (2002) and Charron and Lapuente (2010) have looked at how the level o...