1 Animals in the Blakean Field

Little Lamb who made thee (‘The Lamb’ E8)

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry? (‘The Tyger’ E24)

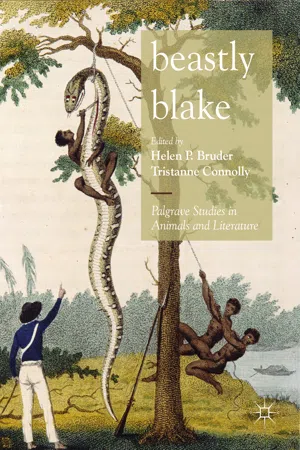

One answer to both of these famous questions could be, ‘Blake’. The importance of animals to his creative work is abundantly clear from these two Songs which are immediately, globally associated with Blake in the popular imagination. But in the academic world, his animals have been unfairly overshadowed by the ‘human form divine ’ (E13). Perhaps the human intellect seeks to affirm itself by granting only to itself the worth of study, but Blake resists such rational self-reflection by ensuring the otherness of other creatures is ever-present. Non-human beings abound in Blake’s illuminated books. 2 They are pervasive not only in his widely studied and widely beloved Songs, where beyond Tyger and Lamb there are lions and wolves, sparrows and robins, the wandering emmet, and the fly that raises the challenging questions, ‘Am I not / A fly like thee? / Or art not thou / A man like me?’ (E23). Such beings as the worm in Thel and the lark in Milton play unforgettable roles in Blake’s illuminated verses. And, indeed, the possibility that ‘conversing with the Animal forms of wisdom’ (FZ 138:31, E406) is essential to the whole process of Blake’s work arises in the allegory of printing in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell , where the creation of books involves ‘a Dragon-Man’ assisted by ‘a number of Dragons’, several ‘Viper[s]’, ‘an Eagle ’ and ‘Eagle like men’, and also ‘Lions ’, before ‘Unnam’d forms’ finish the job and the productions are ‘reciev’d by Men’ and ‘arranged in libraries’ (15, E40). Animals often dominate the illuminated books’ designs as well, whether on the large scale, like the coiling serpents of Europe a Prophecy , or the minute, like the interlinear animal and insect inhabitants of their pages. There are composite creatures, such as the striking portraits in Jerusalem of the melancholy, contemplative (and, from a playful view, a bit rude) swan woman and cock man (11, 78); there are winged human forms, most predominantly the bat-winged figures that become associated with that major player in Blake’s mythology, the Spectre . Beasts preoccupy some of his most famous visual art beyond the illuminated books, too, such as the 1795 Large Colour Prints which feature the bizarre menagerie pictured in Hecate, or The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy , the ethereal horse of Pity , and more strange animal-human hybrids in Satan Exulting Over Eve and, of course, Nebuchadnezzar . In his commercial engravings and book illustrations, also, Blake’s preoccupation with animals comes through, for instance in the different species of monkeys pictured in his engravings for Stedman , not to mention the skinning of the Aboma snake whose bemused look rivals that of the Tyger , and in the magnificently fanciful variations on personification of cat and goldfish in the designs for Gray.

The scholarly inattention to all of these animals in favour of human self-attention may arise from an overly literal and exclusive reading of Blake’s own celebration of the human. No doubt, the human form is central to Blake’s verbal and visual mythology, but it would be simplistic to conclude from this that Blake would endorse Pope’s dictum, ‘the proper study of Mankind is Man’ (Pope [1733] 1963, Essay on Man 2:2). Blake repeatedly emphasises, in mind-bending ways, that the human form mystically informs all—landscape, vegetative life, animal life, divine life, indeed the cosmos—yet does not reduce all to limited human terms. 3 In fact, turning our gaze to Blake’s other life forms raises the possibility that when, at the end of Jerusalem, ‘Lion , Tyger , Horse, Elephant , Eagle Dove, Fly, Worm, / And the all wondrous Serpent clothed in gems & rich array Humanize ’ (98:43–4, E258), it is not so much to alter and absorb the animal as to extend to other forms of existence a level of agency and value typically reserved for humans. This, on the contrary, radically decentralises the human. So much so that Blake extends humanization beyond animate creation : ‘All Human Forms identified even Tree Metal Earth & Stone. all / Human Forms identified’ (J 99:1–2, E258). ‘Even’ emphasises that Blake is leading us through a progression of realisation, in which animals come first, as if they are the first step in seeing the whole world differently. Blake gives animals a pivotal position in that ultimate event, the Last Judgment, in both Milton a Poem and Vala, or The Four Zoas . At the close of Milton, apocalypse erupts when ‘All Animals upon the Earth, are prepar’d in all their strength / To go forth to the Great Harvest & Vintage of the Nations’ (42[49]:39–43[50]:1). And at the close of Vala, the personified sun ‘walks upon the Eternal Mountains raising his heavenly voice / Conversing with the Animal forms of wisdom night & day / That risen from the Sea of fire renewd walk oer the Earth’ (138:28, 30–2, E406). Animals are prominent participants in both the terror that brings, and the wonder that succeeds, the regeneration of the earth.

In this collection we do once again what we have done in our previous volumes: call attention to a crucially important and exciting element in Blake’s work that has been a blind spot in criticism. Once again the blindness may be due to the power of this shift of focus to unsettle received ideas: as those lines from Milton and Jerusalem show, consideration of non-human sources of inspiration has an apocalyptic impact on what has traditionally been seen as Blake’s androcentric universe. Beastly Blake will venture into yet wilder territory than Queer Blake and Sexy Blake as it traces how desire thrives on both sides of the thin Blakean human–animal boundary: like Blake, our contributors strive to see themselves both through and within the Tyger’s burning eyes.

Once again we are inspired by previous groundbreaking but unjustly neglected work. Kevin Hutchings , in Imagining Nature: Blake’s Environmental Poetics (2002), presented an incisive revision of Blake’s relation to the natural world, revealing it to be more complex and more positive than previously assumed. This was still in the earlier days of ecocriticism, which is now a burgeoning field in literary studies in general and Romanticism studies in particular—but, strangely, not in Blake studies. 4 And long before animal studies became the strong field it now is, Rodney M. Baine and Mary R. Baine devoted a book-length study to Blake’s creatures: The Scattered Portions: William Blake’s Biological Symbolism (1986). 5

A few articles and book chapters have emerged, showing that critics are beginning to sense that the Blake who declared, ‘all must love the human form, / In heathen, turk or jew’ (‘The Divine Image ’ E12), also spent time ‘conversing with the Animal forms of wisdom night & day’. David Punter’s article ‘Blake: His Shadowy Animals’ appeared in 1997, and David Perkins’s ‘Animal Rights and “Auguries of Innocence ”’ in 1999. Then in 2012 several articles and books approached Blake’s animals from different angles. David B. Morris argued for bio-anthropocentrism in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; Judith C. Mueller used creatures to discuss Blake’s antinomian use of St Paul (with a related essay on animals in Blake’s Eternity , appearing in 2013); Robert R. Rix read ‘The Tyger ’ in relation to the divine and the beastly in eighteenth-century children’s poetry; while Elizabeth Effinger, in our own Blake, Gender and Culture, reinterpreted the eagle and mole of Thel’s motto. Additionally, in Re-Envisioning Blake, Troy Patenaude’s inspiring environmentalist take on Blake’s experience of Felpham , though primarily concerned with landscape, pays some attention to sheep . Peter Heymans’s Animality in British Romanticism: The Aesthetics of Species includes a chapter on Blake and Burke, which, though it gives more attention to Burke, offers a reading of the Lyca poems. 6 Janelle A. Schwartz’s Worm Work: Recasting Romanticism has a chapter devoted to Blake which concentrates on generation and regeneration in The Book of Thel and ‘The Sick Rose’. Since then, Kurt Fosso’s ‘“Feet of Beasts”: Tracking the Animal in Blake’ (2014) is the only piece to have taken up that sudden rush of interest in Blake’s creatures. These divergent studies only underscore the fact that, even though Baine and Baine (1986, 3) established thirty years ago that ‘No other English poet or artist used biological images and symbols—beast, bird, insect, reptile, fish, tree and plant—more often or more meaningfully than did William Blake’, none of the many Blakean trends, waves, and critical fashions has given his creatures their due place in Blake’s creative cosmos.

Now, with the insights of ecocriticism, animal studies, and posthuman studies, we can take such a focus much further interpretively than Baine and Baine were able to, beyond traditional understandings of Blake. They determinedly focused on the Blakean notion that ‘all forms of life, like the rest of creation , were originally part of man himself’ (Baine and Baine 1986, 6), and firmly situated Blake’s creatures in Western traditions of animal symbolism. But now it is Blake’s contrary fascination with non-human forms in their otherness which arrests our contributors, and which Beastly Blake will show has amazing power to radically transform perception of many critical preoccupations: gender dilemmas, naturally, but also questions of politics , aesthetics, history, identity , linguistics, religion, science, and much more. This new orientation casts bright light on one of Blake’s most famous aphorisms, ‘for every thing that lives is holy, life delights in life’ (America 8:13), and divinely sanctions our need to lis...