“Camp Munsingwear ” at War

When the employees of the Northwestern Knitting Company in Minneapolis received the 1917 May volume of the monthly company magazine, the Munsingwear News , they were met by the Star-Spangled Banner on the front page. It was framed by President Wilson’s “Message to Congress,” where he asked for a “Declaration of State of War with the Imperial German Government.” The President assured that the United States’ motive for entering the war in Europe was not revenge “but only the vindication of right, of human right” and that the United States was “only a single champion.”1

The president of the Northwestern

Knitting Company, Frederick M. Stowell, took for granted that “every employee of this Company has read and read carefully and thoughtfully President Wilson’s appeal […].” In fact, he expected the employees at the company, whatever national background they had, to stand up for the United States at war:

I have not the slightest doubt of the loyalty of every one of you to this Country—your Country and mine. You have been so thoroughly loyal and faithful to this Company and have shown it so consistently that the spirit of loyalty has become a part of you, one of your natural attributes, and such being the case, I know that this same feeling must prevail in you as regards to your Country. I feel confident that no matter what part of the world may have been your birthplace that you will and do fully appreciate that this Country is now your home, and as such deserves and will have your undivided, loyal support. (italics in original)2

Stowell, thus, tried to connect the imagined community of “the Munsingwear Family ” with their likewise presumed imagined community of “the American Nation ” at war. He assured the “Munsingites ”—the nickname of the employees of the Northwestern Knitting Company—that he spoke to them “as representatives by birth of nearly all the nations of the world, but today as true, loyal, faithful, free Americans.”

Stowell also gave substance to the connection between the Company and the

Nation by expecting every loyal “

American ” employee of the company to work harder than ever:

We can all “do our bit” by doing the thing we have been doing and are qualified to do, but we must do it better—do it more efficiently—do more of it—put our whole souls into our work, with the thought always in mind that in doing so we are contributing to the welfare of our Country, the perpetuation of its institutions, the security of its (our) homes.

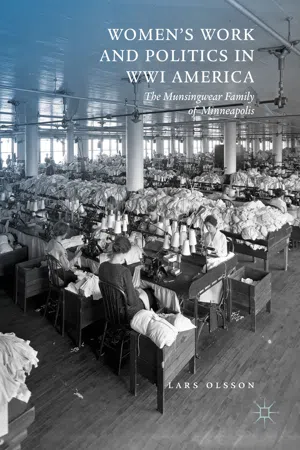

Since the company had a state contract to make underwear—Munsing Wear—for the soldiers at war, the directors and the employees could claim that they not only contributed to the welfare of the Nation but also made a considerable contribution to the war efforts, although garment work is not normally included when women’s work in wartime is highlighted.3 Indeed, this involvement in the war production was deeply imprinted in employees of the company. Alice Larson , for instance, told descendants of hers that she was paid by the government when she knitted fabric for army underwear during the war. Alice, aged 20 in 1918, worked carefully and kept her machine running all the time. She reminded herself that she made really good productivity at work.4 She did her bit for the war effort.

Certainly, company president Stowell included himself and the other directors among those who should do their bit, but the workers could not miss his appeal for more efficiency at work on their part. The directors introduced “scientific management ” at the plant and asked for a great deal of self-sacrifice by the employees as part of their contributions to the war effort. Certainly, he did not tell the employees about the large company profits and the dividends to the stockholders. The Northwestern Knitting Company could do “business as usual ” during wartime; in fact, it did better business than before. In his concluding report for the fiscal year 1917, Stowell told the stockholders that the company “in addition to our regular business, furnished our Government, for use in the army of the United States, many thousands of pieces of underwear.”5 The editor of the Munsingwear News added that “[b]usiness from both old and new accounts [was] being booked in a highly satisfactory manner,” so there was “no gloom in Camp Munsingwear over reports coming in from the front line (my italics).”6 The Northwestern Knitting Company was part of the US home front, partly by contributing to the economic war effort, and partly by making all employees into loyal Americans in support of the war. In this book I will explore those two intertwined processes.

“… the Problem of Women in Industry Is Growing Greater Every Day”

When the United States entered the war in Europe, women’s gainful employment outside their homes was put on the political agenda, because a lot of women replaced men who were drafted for war. Some of them were exploited in a way that went beyond what was acceptable for public opinion. In a report by the Women in Industry Committee of the Bureau of Women and Children at the Minnesota State Department of Labor and Industries in December 1917, its chairwoman, Miss Agnes Peterson ,7 claimed that “the problem of women in industry” was “growing greater every day.”8 In March 1918, the committee started a survey of wage-earning women in Minnesota that had “a double object in view.” First, it should “obtain accurate data about the growing number of women wage earners and the conditions under which they worked and lived.” Second, it desired that the data “could be used in the shaping of a constructive policy for the protection of women wage earners.”9

Altogether, the committee collected information on more than 51,000 female workers in Minnesota; a full third of them worked in manufacturing.10 Information on every single woman was collected regarding name of firm, name of employee, home address, age, country of birth, nationality, kind of work, wages per week, whether the women were living at home or not, whether they contributed to family support or not, marital status , if their husband or son(s) were in army or navy, their husband’s present employment and wages per week, and the age of any children they might have.11

There was a wide variety in earnings, but no fewer than 35% of the women earned less than $10 per week, and the committee considered it to be a “remarkable fact” that one-third of the wage-earning women in Minnesota did not earn “a minimum subsistence wage.” Another third earned enough to live on that level but no more, so the committee concluded that more than 70% of gainfully employed women “received sufficient wages for only a bare existence or less.” Notwithstanding, more than 28,000 wage-earning women—single and married, widows and divorced, deserted or separated—had family obligations and contributed to the support of their families. The survey included 3779 mothers with 7206 children below laboring age. More than half of the women who earned less than $10 per week contributed to the family economy , so although they generally were not primary breadwinners, the committee concluded that it was “hardly possible to excuse low wages for women workers on the ground that they [had] no family responsibility.”12

In Minneapolis alone, 3100 industrial workplaces were surveyed, covering 19,128 wage-earning women.13 The majority of the workplaces were concentrated in the Central District, where close to 82% of the women were gainfully employed.14 Since there were severa...