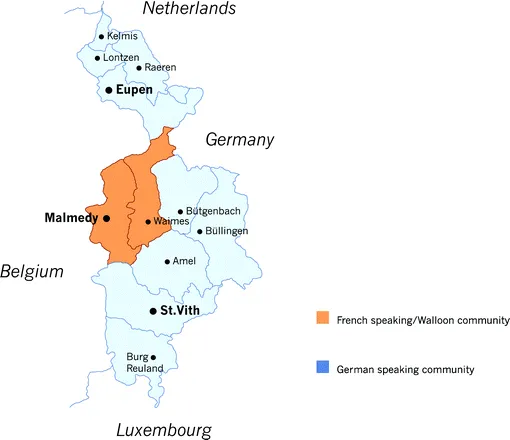

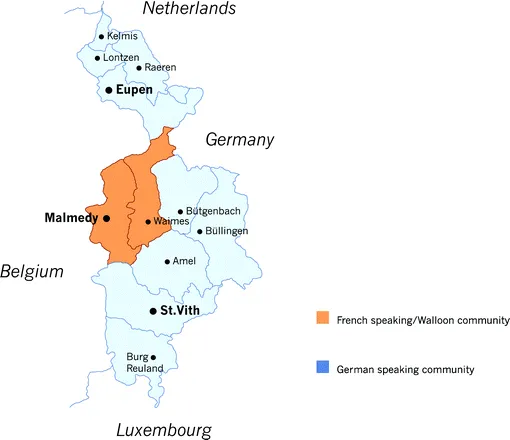

Straddling the frontier between Belgium and Germany, with Luxembourg to the south and the Netherlands to the north, the territory encompassing Belgium’s Eastern Cantons of

Eupen ,

Malmedy and St Vith rested for centuries on the cusp of conflict and compromise.

1 The outbreak of the Great War in 1914 set in train a series of events that would see these

Kreise, which since 1815 occupied the most westerly corner of the German Reich, once more become the focus of renewed claims and counter-claims by rival protagonists. In January 1919, representatives from the victorious nations set about to once more reconfigure the map of Europe at the Peace Conference in Paris.

2 It is only as a consequence of the Treaty of Versailles that the term ‘Eupen-Malmedy’ came into being, for the sake of political expediency.

3 This convenient creation owed much to the diplomatic dexterity of Belgium’s foreign minister and senior plenipotentiary to the

Paris Peace Conference ,

Paul Hymans .

4 As part of the post-war process of territorial amputation, Germany was forced to cede Eupen-Malmedy conditionally to Belgium, pending the outcome of a popular consultation in the territory within six months of the

Versailles Treaty becoming effective (Fig.

1.1).

The Kreis of Malmedy encompassed an area of 813 square kilometres with 36,916 inhabitants. While the vast majority of Malmedy ’s population identified as German, this number included around 10,000 Walloons who, for over a hundred years, had been subjects of the Kaiserreich. 5 More than half of these were concentrated in the town of Malmedy , with the remainder residing in the surrounding hinterland of ‘Prussian Wallonia’.6 The Kreis contained fourteen town councils or Gemeinderat, four of which were solidly Walloon, three mixed and eight German; one of these was St Vith . The town of Malmedy itself had just 6,000 inhabitants, and was largely dependent on its famed paper milling and tanning industries.7 Eupen was geographically a much smaller Kreis than Malmedy , at just 176 square kilometres, albeit more densely populated. From the fourteenth century, Flemish weavers from Bruges and Ghent had established themselves in Eupen , beginning a tradition of textile production era (Fig. 1.2). By the turn of the twentieth century, the majority of Eupen ’s 27,360 inhabitants were in the main employed in textiles, weaving, or agriculture.8 By the end of the war, the town of Eupen had a population of around 15,000. As was the case with Eupen , the surrounding towns of Hergenrath, Eynatten, Kettenis, Lontzen, Neutral Moresnet , Walhorn, and Raeren were overwhelmingly German-speaking.9 Now, in the wake of the war, the inhabitants of these two Kreise would have to accommodate themselves to a new reality, as these former subjects of the now-defunct Kaiserreich prepared to become Belgian. This significant alteration to the status of this borderland territory was just the latest in its long and complex history.

From the latter half of the sixth century, Irish Columban monks introduced Christianity to the southern Rhineland, culminating in the founding of the abbatial principality of Stavelot-Malmedy in 651 by a community of Frankish monks. Malmedy fell under the auspices of the diocese of Liège, while Stavelot was attached to the diocese of Cologne.10 As a consequence of the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the principality of Stavelot-Malmedy became absorbed into Middle Francia following the tripartite division of the Carolingian Empire.11 However, the principality continued to be an independent state within the Holy Roman Empire up to 1795.12 Like Malmedy , Eupen also formed part of Middle Francia (later Lotharingia), and from the eleventh century became part of the Duchy of Limburg.13 St Vith dates back to 836 as a medieval settlement. From the late twelfth century, it served as the customs post for the dukes of Limburg. As a consequence of the battle of Worringen in 1288, these territories were annexed by John I of Brabant. From the fifteenth century up to 1795, they fell under the control of the dukes of Burgundy and later the Habsburg dynasty: the Spanish Habsburgs until 1700 and, after the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, the Austrian Habsburgs.14

The incorporation of Eupen , Malmedy and St Vith into the French Republic following the Revolution saw these cantons eventually comprise the department of l’Ourthe, with Liège as prefecture.15 As part of this new dispensation, a newly designated arrondissement of Malmedy was made up of eleven cantons, including those of Malmedy , Eupen and St Vith . Following the defeat of Napoleon in the summer of 1814, the Treaty of Paris defined the new borders of post-Napoleonic France. However, a number of territorial decisions remained to be resolved. The Congress of Vienna later that year oversaw a redrawing of the European map, and among the territorial transformations, Prussia was granted the greater share of Saxony as well as parts of Westphalia and the Rhine Province. The twin towns of Stavelot and Malmedy , along with the ancient abbey, would henceforth be divided between two separate states. Stavelot was claimed by the newly constituted Kingdom of the Netherlands (after 1830, it was absorbed into the newly independent Kingdom of Belgium), while Malmedy together with Eupen was ceded to Prussia. Malmedy , Eupen and St Vith would henceforth be located within the Grand Duchy of the Lower-Rhine inside a newly enlarged Prussia.16 Following their annexation, Malmedy , Eupen and St Vith were then divided between separate Länder—Jülich-Kleve-Berg and the Grand Duchy of the Lower Rhine (Großherzogtum Niederrhein).17 The two provinces were governed from Cologne and Koblenz respectively. These two provinces would eventually merge in 1822 to form a single Rheinprovinz. From 1816, the Regierungsbezirk of Aachen had responsibility for the Kreise of Eupen , Malmedy and St Vith , the latter Kreis having been reattached to Malmedy in 1821.18

The immediate consequence of the appearance of these new frontiers was the emergence of linguistic minorities, this latest dissection, taking little account of the historical and linguistic complexities of the region. The new borders cut arbitrarily through centuries of tradition and community.19 Yet in the fifty years or so following its annexation by Prussia, the Walloon inhabitants of Malmedy were, in the words of the revered abbot Nicolas Pietkin of Sourbrodt (a village on the outskirts of Malmedy ), quite ‘à l’aise’ with their minority status inside Germany, and ‘worried only for themselves’, as opposed to wanting to be united with their fellow Walloons on the far side of the German border.20 Pietkin never advocated ceding from Prussia, in spite of the limitations placed on his own activities under Bismarck’s Kulturkampf.21 He believed that most of the Walloon population at that time preferred to be part of a ‘little Walloon patrie within a greater Prussian patrie’.22 When King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia paid a visit to Malmedy in 1856, he blissfully proclaimed his pride ‘to have in my kingdom a little country where French is spoken’.23 The coming to power of Bismarck in 1862 resulted in a souring of the relationship between the Walloon community and the Prussian state.24 The culture struggle or Kulturkampf that accompanied the establishment of the unified German state in 1871 saw the level of mutual respect that had existed between the minority Walloon and majority German communities very quickly eroded, but not entirely obliterated.25 Bismarck’s Kulturkampf, described by its critics as ‘Germanisation in excess’ (albeit initially a war against the power of the Catholic Church ...