1 Introduction1

Taxation is a highly studied subject in Latin America. However, even after all the research conducted, all analyses and policy advices given, despite numerous international advisory missions dedicated to tax systems overhaul, and several tax reforms undertaken in the last few decades, many of the central problems and weaknesses of Latin American tax systems remain unaltered. Tax systems in the region lack to ensure market efficiency, secure macroeconomic stabilization, or enhance equality via redistribution, the three basic functions generally assigned to fiscal policy (Musgrave 1959). Even after more than a decade of economic bonanza and rising state income, thanks to the global commodity boom, today it seems more plausible than ever that taxation is the Achilles heel of Latin American democracies.

Not only the evaluation of the progress and continuities in Latin American tax systems is mixed, but also the outlook for positive changes in the future is doubtful. In fact, tax policy in Latin America is facing a moment of uncertainty as important changes in economic, political, and social conditions are taking place that affect the region. At a global level, Latin American countries face decreasing prices of their most important export products, mainly commodities, unpredictable policy changes by the new US government and a resurgent global protectionism. At the domestic level, the economic slowdown rises social demands and political polarization in a moment in which new ruling coalitions have taken over in several countries.

Uncertainty not only describes the political and economic contexts of the region, which one could argue is not all too new given Latin America’s troubled history, it also describes the crisis of the research on taxation and the questioning of the grand paradigms of tax policy. While in the 1990s most governments in Latin America responded to slow economic growth with liberal tax reforms, during the years of the commodity boom governments relied on a pragmatic adaption of their tax systems, taking advantage of the upward commodity cycle but relinquishing structural reform. Many countries in the region adjusted the taxation of extractive sectors taking advantage of windfall profits, broadened tax bases, or modified tax rates. If equity enhancing tax reforms were introduced, their overall effect was marginal or their existence temporary. Now, as the economic super cycle has come to an end and fiscal imbalances are on the rise, pressure for structural tax reforms increases. Still, if such reforms resemble those established in the 1990s or take a proequity stance, as wished by many observers (Bárcena & Kacef, 2011; Corbacho, Cibils, & Lora, 2013) is uncertain. Current major reforms, such as in Ecuador and Colombia in 2016, which increased value added tax (VAT) rates by 2 or 3 percentage points, however, may glimpse some patterns.

This book contends that the causes that impede the overcoming of persistent and recognized challenges of Latin American tax systems have to be understood more thoughtfully. The perspective of how taxation is studied must be adjusted before tax policy can actually change for good. For this, a new approach to studying taxation is necessary, which is useful not only for understanding the complexity of taxation but also for leading to recommendations and changes.

This book offers this approach, emphasizing that tax analysis has to take three neglected dimensions into account: the relational, the historical, and the transnational dimensions of taxation. Applying these dimensions, as the chapters in this book do, can provide vital results to confront the social, political, and economic challenges of taxation in Latin America in times of uncertainty. Following this approach, the chapters in this book investigate diverse key topics in taxation, addressing singular or comparative country case studies and providing desired answers to uncover the real and persistent causes of the limitations in regional tax regimes.

Before describing the relational, transnational, and historical dimensions of taxation and their value for tax analysis, the shortcomings of the prevailing research on taxation are revised and the need for a new approach to taxation is clarified. Finally, the seven contributions included in the book as well as their significance for the three dimensions of this book’s perspective are presented.

2 Taxation in Latin America: Progress and Challenges

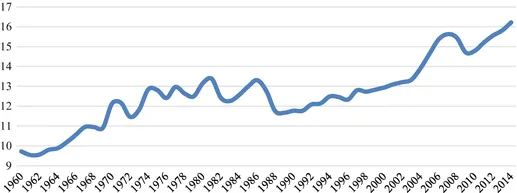

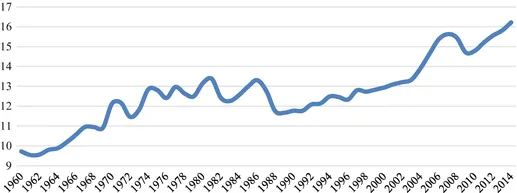

Tax systems in Latin American countries underwent significant changes since the turn of the century; one particular characteristic of these changes is the outstanding rise in the level of tax collection experienced in the region. Yet, the full dimension of this transformation is best appreciated once the long-term

development of the tax state in Latin America is taken into account. Following the data set by

Morán and Pecho (

2016) for central government

tax revenues of 18 Latin American countries, revenue

collection rose by 6.5 percentage points of GDP

during the last five decades, from an initial 9.7% of GDP

in 1960 to 16.2% in 2014. Within these five decades, different periods of tax system’s evolution can be observed, which reflect distinctive approaches to tax policy in the subcontinent (see Fig.

1.1).

Principally, four periods can be distinguished. First, the period starting in the 1960s and ending with the oil crisis in 1970, which was characterized by a paradigm shift in tax policies. In particular, this was the period when the Alliance for Progress established the “ Joint Tax Program,”2 which soon became the main actor in the reform of tax systems in Latin America (Tanzi, 2013). Furthermore, in the 1960s developments in Public Economics began to give relevance to taxation not only as a collecting tool but as a developmental one. Thanks to these shifts and a positive macroeconomic situation, this was the period with the highest increase in the last five decades, although starting from a relatively low level. Latin American tax collection increased by 3.31 percentage points, from 9.54 of GDP in 1960 to 12.85 in 1975. In fact, the changes were so strong that it is fair to say that taxation was completely overhauled and never looked the same (Morán & Pecho, 2016).

However, the positive transformation in taxation did not prosper in the following period. From 1970s onwards to the end of the 1980s, tax collection did not rise significantly and remained highly volatile instead (see Fig. 1.1). Ideologically, the oil crisis that started around 1973 marked a turning point for certain ideas on taxation. In particular, the period coincided with the advent of supply-side economics, which had its own vision of tax policy emphasizing the reduction in efficiency losses, which it considered to be inherent in taxation. In economic and political terms, this was a period of turbulence, including inflation, fiscal problems, rising debt and frequent regime changes, and the struggle for democracy. Latin American countries experienced strong economic and fiscal crises, in search for a lender of last resort turned to international financial organizations for assistance. The IMF and other “Washington consensus ” organizations did not relinquish to engage but bounded their loans on heavy conditionalities, including a series of tax reforms with a strong emphasis on simplification and efficiency. At the end of this period, taxation in the region reached its lowest value since 1972 (11.67 in 1989).

During the 1990s, taxation in Latin America was very much influenced by the policy paradigm set by the Washington Consensus and the propagation of financial crises experienced at the end of the 1980s. In this third period “liberal tax reforms ” (Cornia, Gómez Sabaini, & Martorano, 2014) set out to strengthen VAT, reduce or eliminate taxes on international trade, decrease rates in income taxes, and broaden tax bases. However, also new “heterodox” taxes were created, such as the tax on financial transactions or simplified regimes for small businesses (González, 2009...