If for a single instant … I could imagine I have lost sight of the character of a gentleman I should have spared this or any other tribunal the task of investigating my conduct.

James Barry, closing speech, court martial at St. Helena (1836)1

[T]he woman who performed the last offices … said Dr. Barry was a female and that I was a pretty Doctor not to know this … [She] seemed to think that she had become acquainted with a great secret and wished to be paid for keeping it. I informed her that all Dr. Barry’s relatives were dead, and that it was no secret of mine, and that my own impression was that Dr. Barry was a hermaphrodite. – But whether Dr. Barry was male, female or hermaphrodite I do not know …

Staff Surgeon McKinnon to the Registrar General of Somerset House (1865)2

I start from the premise … that trans is good to think with: that we can use the transgender experience … as a lens through which to think in new and fruitful ways about the fluidity of [other] identifications.

Rogers Brubaker, trans (2016)3

[L]ocated on the border between historiography and literature, fact and fiction, … biofictions show a pronounced tendency to cross boundaries and to blur genre distinctions.

Ansgar Nünning, ‘Fictional Metabiographies and Metaautobiographies’ (2005)4

His end marked the beginning of James Miranda Barry. A mythos was born, literally and literarily, from the reverberations of Barry’s death. Delivering Barry into cultural reincarnation, that death raised (and continues to raise) pointed questions about gender, identity and representation that render the historical character at the centre of the myth, and the cultural production that has sustained it, an exemplary model for reflecting on the complex border crossings between historiography and literature, fact and fiction that are performed by neo-Victorianism and by life-writing, the two genres that in their combined form and in their specific interpellation of James Barry are key to this book. If neo-Victorian life-writing is about the resurrection of the ‘ex-centric’ nineteenth-century subject so that we can discover versions of ourselves in the mirror of the re-invented past that leads to our imagined future, this resurrection finds particular resonance in the afterlives of James Barry.

5 Self-identified officer and gentleman, yet returned in death to the ‘truths’ of an ostensibly female body, Barry also speaks powerfully to twenty-first-century concerns around transgender. The precise nature of the interaction between these coordinates within the medium of life-writing – James ‘Miranda’ Barry, trans/gender, neo-Victorianism – constitute the central axes around which this study is organized.

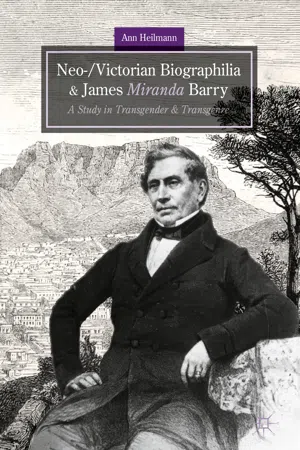

Straddling and crossing the fields of Victorian to neo-Victorian studies and grounded in feminist and gender criticism, this book seeks to undertake a comprehensive conceptualization of neo-Victorian life-writing, or ‘biographilia’, through analysis of the later-Victorian to neo-Victorian remediation of a spectacular case of transgender. The cultural response to Victorian gender crossing, refracted as it is in biography, biofiction and biodrama, can, I contend, serve to illuminate the genre paradigms of neo-historical life-writing. My approach is focused on reading neo-Victorian life-writing through the lens of the cultural construction and representation of James Barry (1789–1865), senior colonial medical officer of the British army from 1816 to 1859. A pioneer of sanitary science and medical reform whose preventative measures anticipated Florence Nightingale’s by over three decades, Barry attained the highest rank in his profession, that of Inspector General.6 Known for his pugnacious, iconoclastic personality during his lifetime, he became the object of intense speculation after his death in 1865 when rumours arose about his sex. These followed a visit to Staff-Surgeon David Reid McKinnon (a doctor long acquainted with Barry who had tended to him in his last illness) by the charwoman who had laid out the body.7 With only one testimony to lay claim to physical evidence of Barry’s bodily condition, and with his female birth identity not confirmed until the latter twentieth century,8 Barry’s ‘real’ sex, gender identity and life circumstances have in the intervening one and a half centuries prompted considerable interest among life-writers, novelists and playwrights.

The cultural appeal of the ‘enigma’ represented by a prominent figure of medical and gender history has, at the time of writing, inspired four biographies, five biodramas, four short stories, seven bionovels (including one in the French medium), a folk-song lyric, and several radio and TV broadcasts.9 Two movie biopics are at different stages of planning and development.10 The proliferation of critical-creative texts and productions that, from the Victorian to the contemporary period, have sought to re-imagine Barry’s life, ranging across the spectrum from literary fiction and experimental stage drama to popular culture, is remarkable. What is particularly striking about the cultural dissemination of the ‘Barry mythos’ is that the historical personality in question was not a prominent writer or artist with an oeuvre that has wide visibility and yet enjoys a measure of the ‘medial framework’ otherwise reserved for what Laura Savu calls the ‘author fiction’ of Shakespeare, Austen, Dickens, the Brontës or Wilde.11 If the figure of Barry touches a cultural nerve, this is evidently because his story of crossing is intrinsic to Victorian, twentieth-century and contemporary interrogations of the sex/gender/sexuality/identity ‘conundrum’.12

My key rationale for using James Barry as a case study to interrogate neo-/Victorian biographilia is that Barry is paradigmatic of the category of instability because of the very uncertainty of any certainty about his story of gender variance. The resulting gender fluidity of cultural representations of Barry, I argue, affords an exemplary model for the genre fluidity of neo-Victorian life-writing. The Barry story helps to illuminate the resisting category of ‘trans*’; like Halberstam’s asterisk, it too opens itself up to a plurality of readings ‘organized around but not confined to forms of gender variance’; by so doing, it ‘modif[ies] the meaning of transitivity by refusing to situate transition in relation to a destination, a final form, a specific shape, or an established configuration of desire and identity’.13 In specifically seeking to tease out the intersectionality of gender and genre in the construction of the cultural memory of Barry, I build on recent queer and feminist narratology,14 in particular Monique Rooney’s argument that the passer acts as a figure of representational instability: ‘The passer cannot exist without a reader who only temporarily engages in passing and is therefore able to disavow his/her part in the crossing. Caught in a mediating role, the passer is a marker of representational transience and is thus a pivotal figure for thinking about figuration and narration’. As a consequence, the ‘representation of passing has historically operated as a kind of metanarrative, a reading of reading’.15 It is this metanarrative about the genre crossings involved in writing and reading the gender crosser that is at the heart of my book. The best illustration of how neo-Victorian life-writing operates is furnished by drawing on an historical figure who features across biography, biofiction and biodrama from the Victorian through to the contemporary period, and who features both as a boundary transgressor and as a boundary marker.

Without doubt a considerable part of the fascination that has ensured Barry a place in the cultural imagination derives from the unknowability of his ‘true’ bodily condition in the absence of any ‘hard’ evidence (in the form of a post-mortem or DNA examination) and, since the discovery of his birth name, of his ‘real’ gender identity: was Barry a woman who disguised herself to lead the life of her choice, an intersex individual, a transman?16 How conclusive in terms of Barry’s sense of self/selves across time is documentary evidence of his original identity? As Marjorie Garber argues with reference to Barry’s older contemporary, the Chevalier d’Éon, the most pressing question arising from historical cases is ‘the relativity of “proof”. According to what canons? Dictated by what exigencies? With what ideological concerns in view: medical, political, social, sexual, erotic?’17 And, one might add, on the basis of what erratic data? Even Barry’s gravestone with his incorrectly recorded date of death testifies to the instability of the subject.18 Just as the desire for neo-Victorian fiction and life writing is fed by our knowledge of the irretrievability of the Victorian past, so it is the unattainability and forever speculative nature of any enquiry into Barry – precisely the mystery that ‘Doctor James’ will not yield up – that has kept the subject of Barry alive.19

There is an element of the spectral to the Barry myth, a cultural haunting visualized in the anecdote of the phantom ‘young officer in Georgian uniform’ reputed to walk the woods in the vicinity of Cape Town that the co-authors of the first biodrama and third novel reference as the source of their interest in Barry and a catalyst for their work: ‘The moment I saw that haunting figure …I wanted to trace her life.’20 In the twenty-first century, which has seen increased momentum in the production of biographilia, Barry’s story continues to exert a ghostly allure. At the end of her 2002 biography, Rachel Holmes invokes the Barry narrative as a quest across the centuries: ‘Dr James Barry has haunted me, but will continue to wander the pathways of our imagination, in search of the spirit of an age, now or in the future, that can accommodate his difference.’21 Barry as a revenant: Terry Castle’s apparitional lesbian here transmutes into the shadowy, only ever partially materializing and therefore eternally irresistible figure of the transman.22 Ghosting is, as Jack/Judith Halberstam notes, one of mainstream culture’s containment strategies to make transgender both visible and invisible at one and the same time.23 My argument, then, revolves around the ways in which Victorian to contemporary life-writing transgenders – or, conversely, spectralizes transgender by heteronormalizing – the persona of James Barry. Given contemporary conceptualization of transgender as an umbrella category, this concept will be the framework for discussion of Barry’s gender variance.24

That the questions about gender and especially transgender that Barry’s story raises are closely connected to present-day concerns is signalled by the vibrancy of recent cultural and political debate. Transgender studies as an academic discipline and a catalyst for community and international activism was established in the 1990s; the twenty-first century has seen the ‘mainstreaming’ of transgender in wider culture.25 This is evidenced in exhibitions on transgender history26 and the rise of non-binarity in the use of gender-neutral titles and pronouns, including legal documents27; in legislation like the UK’s Gender Recognition Act of 2004,28 the House of Commons and Women and Equality Committee’s 2016 ‘Transgender Equality’ report;29 and the decision, in 2013, to remove transgender from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.30 A regular feature in news provision,31 transgender has prompted widespread cultural interest in memoirs, novels and biopics about genderqueer identities and gender-reassignment/confirmation.32 Beyond the mainstream appeal of transgender celebrity culture,33 a broader public is now engaging with questions around intersexuality34 and transgender children and family life35 while also being attentive to high-profile court cases.36 These concerns are addressed in institutional cultures through the implementation of transgender policies37 and public and institutional responses to alt-right endeavour to reverse Equality and Diversity legislation such as the attempt to enforce a transgender ban on the US military.38 Barry speaks to twenty-first-century awareness of gender variance, non-binarism and what Stephen Whittle calls our ‘cultural obsession’ with all matters ‘trans’ as much as the woman warrior in male garb did to twentieth-century feminisms and the swashbuckling heroine to the Victorians in the age of female educational, professional and political campaigns.39

As a gender passer (making the best of gender binarity) who in posthumous representation becomes a gender crosser (transgressor against gender normativity), Barry presents an epistemic challenge to late-twentieth and twenty-first-century thought about transgender (the psychological and experiential grounds for his change of gender and potentially shifting sense of identity over time will remain forever speculative). Barry’s case can thus serve to highlight our own blindspots and ongoing ‘gender trouble’. For that an historical individual with a female birth and male adult identity should to this day predominantly, and insistently, be figured as a woman indicates that historical trans identity is far from being ‘mainstreamed’, and also, perhaps, that we devote more attention to transwomen than transmen.40 Is this because transfemininity is more of a threat: to heteronormativity since it disturbs the commodification of the female body as an object of (straight) sexual consumption; to feminism because it calls into question the key premise that women are subjected to oppression and violence globally because of their innate bodily difference from men? (In approaching James Barry’s representation in life-writing through the combined lens of feminism and transgender, this study seeks to contribute to the bridging of the troubled waters between these two liberation discourses, arguing for inclusiveness in political and cultural practice.)41 As Rogers Brubaker points out, transwomen ‘face more intensive policing than their female-to-male counterparts.’42 Is transfemininity both more challenging and more stereotypically ‘sexy’ than transmasculinity? Or is society less concerned with transmen because they started their journey as girls or women and their gender migration is rationalized as the desire to appropriate the economically and socially ‘dominant’ identity position?

Beyond heteronormative contexts, the complexities of Barry’s life also go some way towards illustrating tensions in transgender studies, as pinpointed by Katrina Roen, between the respective politics of passing and crossing, of adopting ‘either/or’ or ‘both/neither’ identities.43 Placed in his historical background, Barry’s gender performance cuts across both positions. In his determination to protect himself against exposure (when gravely ill, he issued instructions for his body to be buried in his clothes without examination), the historical Barry was, in Kate Bornstein’s terms, a ‘gender defender’, an upholder of the sex/gender system.44 (Given historical conditions and his choice of career, it is of course questionable how he could have acted otherwise; the constraints to which the socially more privileged Chevalier d’Éon was subjected offers a good illustration of the dangers of crossing).45 In Brubaker’s more recent, less value-laden terms, Barry’s life offers an historical angle on the ‘trans of migration’: ‘moving from one established sex/gender category to another’.46 At the same time, Barry’s spectacular over-performance of both masculinity and femininity mark him out as one of Bornstein’s ‘gender outlaws’ (seeking ‘every opportunity of making himself conspicuous’, Barry sported ‘the longest sword and spurs he could obtain’, while displaying the voice, diminutive size and habits of a ‘woman’).47 Brubaker’s model refers to this as the ‘trans of between’: ‘defining oneself with reference to the two established categories, without belonging entirely or unambiguously to either one’. (Brubaker’s third position, ‘trans of beyond’, which transcends the gender binary through deliberate resistance to categorization, was adopted by the Chevalier d’Éon and is played out in postmodern biofictional representations of Barry such as Patricia Duncker’s).48 The particular challenge Barry posed with a gender performance that mixed gender stereotypes will be considered in the third chapter’s discussion of Barry caricatures.

Passer and crosser, ‘trans-migrant’ and ‘trans-betweener’, gender changer and gender challenger at once: from a twenty-first-century perspective Barry can convincingly be placed in a transgender context.49 The question that this book investigates, however, is not so much whether Barry was ‘actually’ a transgender individual as, rather, what complexities arise from applying – or withholding – contemporary identity categories to historical subjects and how this translates to biographical, biofictional and biodramatic constructions of the figure under review. For, as this study will illustrate, the majority of texts across the 150 year time period covered (1865–2016) cast Barry as a cross-dressing woman rather than a transman. That this is also the case in recent textual production runs counter to contemporary developments in postmodern studies, where, as Halberstam notes, ‘the transgender body has emerged as futurity itself, a kind of heroic fulfillment of postmodern promises of gender flexibility’.50 The frequency of references in my book to Barry’s ‘masquerade’, ‘impersonation’ and ‘imposture’ serves to reflect this representation of femininity in disguise embracing masculinity as performance. The emphasis of most biographilic works is on the protagonist’s process of enacting and in the act imperceptibly ‘becoming’ rather than ‘being’ James Barry. Even though in many of these texts Barry remains essentially (or remains essentialized as) a woman, the attention paid to processes of transformation resonates with contemporary transgender theory and experience: as Virginia Goldner observes, transgenderism constitutes ...