Scientific knowledge seeks to establish relations between objects. The objects can be mental or physical. Formal sciences study the relations between mental objects, whereas factual sciences study the relations between material objects. Mathematics and logic are examples of formal science; physics and economics are instances of factual sciences.

Scientific knowledge takes the form of propositions that intend to be error-free. Scientific knowledge is therefore a particular type of human knowledge. What would be the criterion to accept or reject a proposition as scientific? It depends upon the type of science. In the formal sciences, the criterion seems to be rather straightforward: The relations established must be free of internal logical contradictions, as in a mathematical theorem.

In the factual sciences, by contrast, the criteria are more involved. As will be shown in this book, factual science propositions are based on formal science propositions; that is, the propositions of a factual science must also be free of internal logical contradictions. However, this rule constitutes just a necessary condition, for the propositions must also be confronted against real-world data.

Scientific knowledge in the factual sciences can be defined as the set of propositions about the existence of relations between material objects together with the explanations about the reasons for the existence of such relationships. Therefore, it seeks to determine causality relations: what causes what and why. It also seeks to be error-free knowledge, as said above.

We can think of several criteria to accept or reject a proposition in the factual science. Common sense is the most frequent criterion utilized in everyday life. Common sense refers to human intuition, which is a strong force in human knowledge. Intuition is the natural method of human knowledge.

The assumption taken in this book is that intuitive knowledge is subject to substantial errors. Intuitive knowledge is based on human perceptions, which can be deceiving. Galileo’s proposition that the Earth spins on its axis and orbits around the sun was not generally accepted for a long time (even up to now) because it contradicted intuitive knowledge: People cannot feel the Earth spinning and what they can see is rather that the sun is going around the Earth. The same can be said about today’s climate change because the greenhouse gases are invisible to human eyes. Intuitive knowledge is thus the primitive form of human knowledge.

As said earlier, science seeks to produce error-free human knowledge. Therefore, human knowledge in the form of scientific knowledge requires the use of a scientific method, which needs to be learned and educated. Thus, science has to do with method. Thus, the criteria for accepting or rejecting propositions as scientific in the factual sciences—the scientific method—needs to be constructed. This construction is the task of epistemology.

The Role of Epistemology in Scientific Knowledge

In this book, epistemology is viewed as the field that studies the logic of scientific knowledge in the factual sciences. Epistemology sees scientific knowledge as fundamentally problematic and in need of justification, of proof, of validation, of foundation, of legitimation. Therefore, the objective of epistemology is to investigate the validity of scientific knowledge. For this we need a criterion to determine whether and when scientific knowledge is valid. This criterion cannot be based on facts, for they are the objective of having a criterion; thus, the criterion can only be established logically. Scientific knowledge must have a logic, a rationality, established by a set of assumptions. Therefore, the criterion is given by a theory of knowledge, which as any theory is a set of assumptions that constitute a logical system.

Epistemology will thus be seen as theory of knowledge, as a logical system. In this book, the concept of theory will be applied to the logic of scientific knowledge as well as to the scientific knowledge itself. Consequently, two very useful definitions in parallel are needed at the very beginning:

Theory of knowledge is the set of assumptions that gives us a logical criterion to determine the validity of scientific knowledge, from which a set of rules for scientific research can be derived. The set of assumptions constitutes a logical system, free of internal contradictions.

Scientific theory is the set of assumptions about the essential underlying factors operating in the observed functioning of the real world, from which empirically testable propositions can be logically derived. The set of assumptions constitutes a logical system, free of internal contradictions.

Any factual science needs to solve the criterion of knowledge

before doing its work because this question cannot be solved

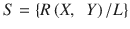

within the factual science. The logical impossibility of obtaining the criterion from within the factual science is relatively easy to proof. Let S represent any factual science. Then

Factual science (S) is a set of relations (R) between material objects X and material objects Y, which are established according to criterion (L).

This proposition can be represented as follows:

How would L be determined? If L were part of S, then L would be established through the relations between physical objects, that is, relations between atoms (physical world) or between people (social world); however, this leads us to the logical problem of circular reasoning because we need L precisely to explain the relations between atoms or between people.

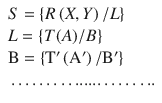

The criterion L will thus have to be determined outside the factual science. How? The alternative is to go to the formal science, in particular to the science of logic. The criterion L is now justified by a logical system. This logical system is precisely the theory of knowledge (T), which as any theory is a set of assumptions (A). Then we can write

The first line of system Eq. (1.2) just repeats the definition of factual science. The second says that criterion L is logically justified by deriving it from the theory of knowledge T, which includes a set of assumptions A, given the set of assumptions B that is able to justify A. The set B constitutes the meta-assumptions, the assumptions underlying the set of assumptions A. The set B is logically unavoidable, for the set A needs justification. (e.g., why do I assume that there is heaven? Because I assume there is God? Why do I assume that there is God? Because…, etc.). Therefore, the set B needs a logical justification by using another theory T′, which now contains assumptions A′, which in turn are based on meta-assumptions B′, and so on. Hence, we would need to determine the assumptions of the assumptions of the assumptions. This algorithm leads us to the logical problem of infinite regress.

The logical problem of infinite regress is a torment in science. A classical anecdote is worth telling at this point (adapted from Hawking

1996, p. 2):

An old person challenged the explanation of the universe given by an astronomer in a public lecture by saying:

The scientist gave a superior smile before replying:

“What is the tortoise standing on?”

“You’re very clever young man, very clever,” said the old person. “But it is turtles all the way down.”

How could science escape from the infinite regress problem? This is a classical problem, the solution of which goes back to Aristotle’s “unmoved mover.” Everything that is in motion is moved by something else, but there cannot be an infinite series of moved movers. Thus, we must assume that there exists an unmoved mover.

In order to construct scientific knowledge, we need an unmoved mover, an initial point, established as axiom, without justification, just to be able to start playing the scientific game, which includes eventually revising the initial point, and changing it if necessary. The scientific game includes the use of an algorithm, that is, a procedure for solving a problem by trial and error, in a finite number of steps, which frequently involves repetition of an operation. Thus, the initial point is not established forever; it is only a logical artifice. If the route to his desired destination is unknown, the walker could better start walking in any direction and will be able to find the route by trial and error, instead of staying paralyzed.

In the system Eq. (1.2) above, the only way to avoid the infinite regress problem in the theory of knowledge is by starting with the meta-assumption B as given, and thus ignoring the third line and the rest. Then the set of assumptions B will constitute the foundation or pillar of the theory of knowledge T, which in turn will be the foundation or pillar of the criterion L, which we can use to construct the theory of knowledge. The infinite regress problem is thus circumvented and we are able to walk.

The role of the theory of knowledge in the growth of scientific knowledge is to derive scientific rules that minimize logical errors in the task of accepting or rejecting propositions that are intended to be scientific knowledge. The theory of knowledge needs foundations, that is, meta-assumptions. Consider that the meta-assumptions B of the current theories of knowledge include those listed in Table

1.1.

Table 1.1Meta-assumptions of the theory of knowledge

(i) Reality is knowable. It might not be obvious to everyone that this proposition is needed, but reality could be unknowable to us |

(ii) Scientific knowledge about reality is not revealed to us; it is discovered by us |

(iii) Discovery requires procedures or rules that are based on a single logical system, which implies unity of knowledge of a given reality; moreover, there exists such logical system |

(iv) There exists a demarcation between scientific knowledge and non-scientific knowledge |

As shown earlier, these meta-assumptions need no justification. (Please do not try to justify them! We need to move on.) Thus, this initial set of assumptions constitutes just the beginning of an algorithm to find the best set of assumptions. Given these initial or fundamental assumptions, we have a rule to follow: Any particular theory of knowledge will have to be logically consistent with these four general principles.

In Table 1.1, assumption (i) implies that we may fail to understand a reality because it is unknowable. Examples may include chaotic systems (weather), rare events (earthquakes), and ancient civilizations where facts are limited. Assumption (ii) in turn implies that research is needed to attain scientific knowledge. According to assumption (iii), a theory of knowledge seeks to provide science with a logical foundation or justification, that is, with a rationality. Therefore, discovery cannot appear “out of the blue.” Accidental discoveries are not “accidental”, but part of a constructed logical system; otherwise, it could hardly be understood as discovery. According to assumption (iv), a theory of knowledge must have a rule that enables us to separate scientific knowledge from pseudo-knowledge in order to have error-free knowledge.

Theory of knowledge is a set of assumptions that constitute a logical system; that is, the assumptions cannot contradict each other. Thus, theory of knowledge can be seen as part of logic, that is, as a formal science. Factual sciences and formal sciences thus interact: theory of knowledge (constructed in the formal science of logic) is needed in factual sciences. Any theory of knowledge has a particular set of assumptions that justify rules of scientific knowledge, in which the set of a...