Like the majority of Americans, I did not expect Donald J. Trump to be elected president of the USA. No more than many in Britain expected Brexit to win the approval of British voters. Yet, like many others, I could also see the possibility that both Brexit and Trump would be triumphant. It did not take great insight or foresight to see that the press, the media generally, many politicians, and virtually all major political parties on both sides of the Atlantic were missing massive populist revolts that seemed all but invisible to the parade of public commentators.

Even while there was much talk of economic recovery, the rate of poverty in the USA reached 17% in 2016. A percentage roughly double that had been in poverty at some point between 2010 and 2013: the same was true for the UK. The official rate of unemployment may have been reduced to below 5% in the US and almost as low in the UK by 2017, but these calculations were badly flawed. If part-time employment was not counted as being in-work, if people were not counted as working when they were nominally “self-employed,” then the rate of “official” unemployment doubled or worse, in the USA and the UK.

In both countries, wages have remained stagnant for the middle classes and have been so for decades. The working classes practically have become invisible in both countries—at least prior to Brexit and the election of Donald Trump —as both nations have abandoned manufacturing, arguing that blue-collar industrial jobs were best done in low-wage countries. The irony is that for many, the UK and the USA have become low-wage countries themselves. But it is worse than that. The middle classes on both sides of the Atlantic have been struggling for decades, facing stagnating incomes at best, or long-term unemployment as many so-called middle-class jobs have either evaporated or been exported abroad.

Conservatives on both sides of the Atlantic point out that this was the inevitable result of globalization and automation. Some say it is because of poor decisions made by the less successful, the impoverished and the uneducated: they failed to get the right skills, or education, their productivity was low, and American and British workers were not competitive. Moreover, Republicans and Tories have argued for decades that labor unions are greedy, practice class conflict, and advocate unreasonable wage hikes that raise prices, lead to inflation, and make products more and more unaffordable. Inevitably, as jobs have disappeared, as wages have stagnated, as millions have failed to participate in so-called recovery, as unions have been eviscerated, and as political parties have failed to respond to the suffering that they have not acknowledged, or simply could not see, the mass parties of the past began to fragment, unsure of who or where their constituencies were.

Constituencies themselves have become more complex, divided by identity politics, regional attachments, social and class divisions, and polarized further by immigration and population movements as both the USA and the UK became less Western, less Christian, and less white. Identity politics have proved especially nettlesome, as gender identity has become more amorphous and ill-defined, and as marriage has become something other than between a man and a woman, challenging traditional white populations already threatened as their neighbors and countries became less Christian and less white. And as whites, particularly the traditional bread-winning male populations, have become more threatened, as their jobs have been eviscerated or exported, as more and more have been displaced, and as they have had to compete with low-wage workers in far-flung countries, Conservatives everywhere have successfully argued that their problems were the result of Big Government: too many taxes, too much support of illegal immigrants, too much protection of trees and certain animal species, too little concern for workers who had nothing to look forward too.

In the midst of these problems, liberals seemed unable to articulate a vision for the future. They became too cozy with Wall Street in the USA and the City in Britain. They became part of the establishment, more and more distant and increasingly unaware of or insensitive toward the suffering of their traditional constituents. On both sides of the Atlantic, the major parties moved to the right, Democrats embracing compromise with Republicans as a way to acquire power, and Tony Blair and Labor doing the same in Britain to accommodate the Tories . For decades, in both the USA and the UK, major political parties accepted the viewpoints of Big Business: keep taxes low, government regulation at a minimum, low or no tariffs at the border, minimal if any carbon tax, weak unions, and strong currencies.

What progressive parties on both sides of the Atlantic failed to do was to adequately acknowledge or grasp the multiple crises at hand. We have been floundering in the USA and the UK now for several decades, following the “end of history,” or at the least the End of Communism as a serious historical force, as to what exactly our alternatives should be in the non-Communist West. It is time now to admit and to fully acknowledge that Europe and the USA have been facing dual crises of capitalism and liberal democracy, and for Europe a continuing crisis of unity.

1 More than crises, the West now faces a historical caesura marking the end of liberalism as we have known it, and the beginning of a new era of authoritarianism that is a reminder of things past, if not a return of history. German historian Philipp Ther, though addressing the failures of the Western model of liberal democracy and economic liberalism in Central and Eastern Europe, has inadvertently put the current crisis in the West in historical perspective. Ther has argued that a “neoliberal train” set in motion by

Margaret Thatcher in Britain and

Ronald Reagan in the USA began to cross into Europe in 1989. He states the problem with clarity:

Blind belief in the market as an adjudicator in almost all human affairs, irrational reliance on the rationality of market participants, disdain for the state as expressed in the myth of “big government,” and the uniform application of the economic recipes of the Washington Consensus. 2

Ther’s thesis was intended to apply to the bungled attempt to transform the former Communist countries of Europe into Western-style capitalist liberal democracies. Yet his thesis uncannily intones some of the notes of the UK and the USA. Both countries are after all the progenitors of neoliberalism and its liberalizing, deregulating, and privatizing progeny, and it is these tenets that have created the mischief that now threatens the very fabric of the social contract in both the UK and the USA, moving both nations toward unintended and unanticipated historical reversions. The social problem, once thought resolved, has returned with a vengeance, revealing that history may be reversible and that some of the worst riddles of the past have remained—just below the surface.

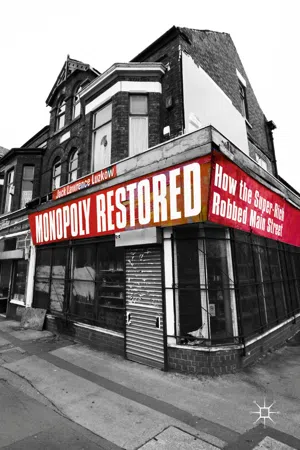

Which is precisely the argument of Monopoly Restored: How the Super-Rich Robbed Main Street. The super-rich—the 1 (or 0.1)% in current lingo—have gotten immensely rich not through sheer ingenuity, or inordinate intellectual ability, but by extracting wealth from the real economy where most of us live and work. Historically, much of the wealth of the ultra-wealthy has been based on inheritance, tax evasion, political influence, or just plain theft. In the last four decades, the menu has expanded. The owners of wealth, whether financial, intellectual, or physical, have largely succeeded in destroying competitive markets and deregulating large parts of the economy, creating large “rents” for themselves. They have forged virtual monopolies in telecommunications and energy, producing outsized profits or “rents” for them. They have insisted that banks retain the right to speculate on derivatives, ensured that credit card companies not be bothered by pesky usury laws, expanded the shadow banking system so that hedge funds and private equity firms remain unregulated and virtually invisible. Their credit card companies have suppressed usury laws limiting interest rates. They have successfully resisted more efficient, less expensive, and fairer single-payer healthcare systems (in the USA), while defending for-profit health insurance that is unaffordable and inequitable for many millions, producing vast rents for their health insurance companies. The super-rich have been granted patents on drugs, even when their drugs are no better than those already on the market. They have won undeserved subsidies for themselves in agribusiness. Their seed companies have established near monopolies over the genetically modified seed market, using political leverage to limit or to eliminate competition. The super-rich who control corporations have practiced wage theft , fought minimum wage laws, weakened unions, outsourced jobs, resorted to temps and contract labor, and preached free trade so the commodities they produce in China and elsewhere can be brought to the USA with minimal duties. The super-rich have lowered (or escaped) inheritance taxes, shifting much of their income to lower-taxed capital gains. They have created tax havens where trillions of dollars remain untaxed and invisible. And multinational corporations have transferred profits of their intellectual and financial property to subsidiaries in low-tax regimes, where they often remain permanently untaxed.

As Chapter 2, “Democracy Corrupted,” explains, the super-rich have accumulated great wealth for themselves by corrupting democracy. They have done this by establishing think tanks that masquerade as neutral and scientific. They have poured large and virtually unlimited funds into political campaigns, promoting and helping to elect candidates who support a neoliberal paradigm that has shredded the social contract. In the USA, in 2010, this has been enabled by a majority decision of the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, granting deep-pocketed corporations the right to spend whatever they wanted on political election campaigns. 3 The UK has much more restrictive campaign finance laws, but that has hardly prevented the City of London from having lopsided influence over number 10 Downing Street.

By influencing and even controlling political parties through campaign contributions, by ownership of large segments of the print and electronic media, where they run disinformation campaigns that confuse truth and propaganda, by the establishment of so-called disinterested think tanks, by employing armies of lobbyists, the super-rich have established a rentier economy that rewards capital while regulating and diminishing labor.

Corrupting democracy has allowed the corporate super-rich to privatize public assets, to limit government oversight on the financial and banking industry and to build new monopolies in everything from telecommunications to (patented) drugs. The super-rich have used political leverage to create “rents” by obtaining undeserved “subsidies” in everything from healthcare to agribusiness, and then used government to reduce taxes on those rents.

Less than a decade after Citizens United , plutocracies in the USA and UK have produced a kind of “extreme” capitalism that has helped transfer considerable financial and political power to Wall Street and the City of London. As is detailed in Chapter 3, “The Rise and Rise of Wall Street and the City of London,” the gravitational pull of Wall Street and the City has given the banking and financial sectors continued leverage to make predatory sub-prime loans, to prevent the restoration of usury laws limiting interest rate charges, and to increase debt to capital ratios once thought dangerous and even lethal. Even post-Dodd–Frank , there is no firewall between investment and commercial banks, hedge funds and private equity firms remain unregulated and can legally access pension funds, and derivatives are again widely traded despite the meltdown they caused during the crash of 2007–2008. Meanwhile, banks have gotten even bigger than they were when they were too big to fail, avoiding antitrust laws that might have prevented the crises of 2007–2008 had they only been invoked.

For every additional dollar generated by the economy, some economists, such as Thomas Piketty and Anthony Atkinson , argue that more than 90% goes to the 1%. Chapter 4, “The Ascendancy of the Corporate Elite,” explains how this happens. During the “golden age,” for several decades following WW II, American and British executives were paid modestly, with rare (and sometimes deserved) exceptions. Beginning with the Reagan and Thatcher eras, executive pay mushroomed while the income of corporate employees stagnated at best. Rising executive compensation was taken as an entitlement: greed was good for the overall health of a firm and the American economy. Corporate executives grew profits—and their personal income—by shifting to short-termism : encouraging employee layoffs, moving companies to low-wage states or countries, evading corporate taxes in the name of greater profitability, acquiring other companies to raise market share and corporate revenues, and using share buybacks to (artificially) raise share value, which was then linked to executive compensation. By packing corporate boards with cronies who were well paid for their services—subsequently raising their own wages completely out of synch with executive performance—and by moving employees into short-term or part-time work, or simply calling them self-employed, the wealth of the corporate 1% was vastly enhanced, much of it at the direct expense of their employees. Corporations also repressed the wages of workers by shifting production—in the USA—to right-to-work states, which are difficult to organize, or by shifting production abroad, made easier by trade agreements mostly favorable to corporations, which in fact help to write those agreements.

The more that the corporate rich take for themselves, the less there is for everybody else: that is what extracting wealth from the real economy means. Chapter 5, “The Decline of Main Street and the Middle Class,” examines how corporations have replaced defined-benefit with defined-contribution pensions , shifting much more of the burden of retirement ont...