eBook - ePub

Economic Analysis and Efficiency in Policing, Criminal Justice and Crime Reduction

What Works?

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic Analysis and Efficiency in Policing, Criminal Justice and Crime Reduction

What Works?

About this book

This monograph explains what economic analysis is, why it is important, and forms it can take in policing and criminal justice. Costs are important in all forms of economic analysis but their collection tends to be partial and inadequate in capturing key information. A practical guide to the collection is therefore also provided.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Economic Analysis and Efficiency in Policing, Criminal Justice and Crime Reduction by Matthew Manning,Shane D. Johnson,Kenneth A. Loparo,Gabriel T.W. Wong,Margarita Vorsina,Nick Tilley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Economic Analysis and Public Policy

Abstract: This chapter explains the rationale for the use of economic analysis to inform policy decisions. Economic analysis can contribute, for example, to setting priorities and plans, identifying the best way of achieving strategic objectives, helping to develop cost-effective plans, informing users as to the policy that can be implemented at lowest cost, identifying which alternative has lowest impact on third parties, providing an analysis on returns on investment, and documenting the decision-making process.

Manning, Matthew, Shane D. Johnson, Nick Tilley, Gabriel T.W. Wong and Margarita Vorsina. Economic Analysis and Efficiency in Policing, Criminal Justice and Crime Reduction: What Works? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. DOI: 10.1057/9781137588654.0006.

Evidence-informed policy

Economic analysis (EA) aims to provide a rational basis for the allocation of scarce public resources. It provides results that promote economic efficiency and good fiscal management by assessing available options to identify those providing the greatest return on investment. EA also allows policymakers to gauge the economic implications of existing policies and/or programmes (Manning, 2004, 2008, 2014).

In practice, factors including political ideology, the mass media and public opinion invariably affect policy decisions relating to resource allocation both between and within policy areas such as health, education, crime, security and transport. What EA offers, however, is salient information with respect to the economic impact of decisions on government budgets, individuals and society more broadly. This can be taken into account in complex policy decisions that could be profoundly important for the future of government (e.g., Boardman, Greenberg, Vining, & Weimer, 2006; Farrell, Bowers, & Johnson, 2005). Economic information is particularly important in improving the transparency of such policy decisions.

Economic analysis

Economic analysis (EA) techniques such as cost-benefit analysis (CBA), cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost-savings analysis (CSA) and cost-utility analysis (CUA) are used in most areas of public policy research including economics, health, environment and, more recently, crime (Farrell et al., 2005; Manning, 2014).1 Each technique provides answers to different questions, and each will be discussed in Chapter 3.

In this chapter, we provide some context regarding the use of EA in the policy development environment and, for illustration purposes, do so with reference to CBA. We discuss CBA here because it is one of the most widely understood techniques. It systematically catalogues benefits and costs, valuing those costs and benefits in a common metric (e.g., pounds) to estimate the expected net benefit (i.e., benefits minus costs) of a decision relative to the status quo.

Individual decision-making is generally orientated to maximising personal utility from a selection of possible alternatives. This perspective is also typically the one taken by individual firms or agencies. CBA extends beyond the individual person or firm to society at large, where all of the societal costs (SC) and societal benefits (SB) are considered. For this reason, CBA is often called ‘social cost-benefit analysis’.

The results generated from CBA provide an estimated aggregate value of a policy as measured by its net social benefits (NSB), where NSB = SB – SC. CBA, therefore, is critical to any comprehensive evaluation, as it considers all key quantitative and qualitative impacts of public or private investment. It allows individuals, businesses or public and private enterprises to identify, quantify, and value the economic benefits and costs of policies over a multiyear timeframe. The information gained aims to help target scarce resources to maximise societal benefits (Manning, 2014; Williams, 1993).

EA can contribute, for example, to (1) setting priorities and plans (e.g., best rate of return for any given budget, or to determine an optimal programme budget), (2) identifying the best way of achieving strategic objectives or goals, (3) assisting in the development of cost-effective designs and strategies, (4) informing users (e.g., policing agencies) as to which policy can be implemented at the lowest cost, (5) potentially providing information on which alternative has the lowest impact on external parties (e.g., residents of a local area), (6) providing an analysis of returns-on-investment, and (7) documenting the decision process (Manning, 2014).

The aspirations of EA are widely understood, and hence there is little opposition to its application. There are, however, two main concerns. The first relates to the fundamental utilitarian assumptions of CBA, where ‘the sum of individual utilities should be maximised and that it is possible to trade-off utility gains for some against utility losses for others’ (Boardman et al., 2006, p. 2). In other words, is it proper to trade one person’s benefits for another person’s costs? The second concern relates to practical issues, such as identifying the impacts that will actually occur over time, methods for monetising these impacts, and ways to make trade-offs between the present and the future (Boardman et al., 2006).

Competing interests and EA

Those occupying different positions within and outside DMUs are liable to see the conduct of EA and its results differently. In particular, analysts (those responsible for undertaking the EA), spenders (those making use of resources in service delivery) and guardians (those responsible for budgets) tend to have different starting points that reflect their roles and responsibilities. While the analyst’s perspective is consistent with the principles of EA, spenders are liable to overestimate social benefits and underestimate social and economic costs. Guardians are liable to discount future benefits heavily and ignore unplanned social benefits. Spenders and guardians are also apt to have different levels of power (which may also change in level and direction over time). The benefits of economic analysis are lost if either spenders or guardians set its agenda (Boardman et al., 2006).

Note

1Note that in other disciplines, such as health, there are thousands of EA studies (Mallender & Tierney [Forthcoming] suggest there are more than 13,000), but EA is in its infancy in crime and justice.

2

Conceptual Foundation of Economic Analysis (EA)

Abstract: This chapter summarises the conceptual foundations of EA and the importance of EA to the decision-making process and the development of policy aimed at moderating crime more generally. In broad terms, it considers how EA can influence the strategic allocation of resources by a crime reduction agency over some time horizon (e.g., the planning of annual budgets), and how it can influence the selection of interventions from a set of alternatives given budget constraints (an activity that may be independent of, or a subordinate element of, longer-term planning).

Manning, Matthew, Shane D. Johnson, Nick Tilley, Gabriel T.W. Wong and Margarita Vorsina. Economic Analysis and Efficiency in Policing, Criminal Justice and Crime Reduction: What Works? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. DOI: 10.1057/9781137588654.0007.

Economics provides a scientific approach to understanding the ways in which families, firms and entire societies allocate resources (i.e., inputs – factors of production that are used to produce goods and services) to satisfy their needs and wants (Taylor & Weerapana, 2012).

EA is used to facilitate the efficient allocation of finite resources so practitioners and policymakers get the most bang for their buck. What may seem, at first glance, efficient and successful, may in fact be found to be relatively inefficient with respect to the translation of inputs into outputs or outcomes. Where such inefficiency is identified (referred to as ‘market failure ’ by economists), there is a prima facie rationale for doing things differently.

This chapter provides a conceptual background for EA in crime prevention. The theory outlined was developed to inform agency decisions over the allocation and use of resources and the selection of specific interventions or programmes for implementation, and hence, it is directly relevant to crime prevention practitioners.

EA in the context of crime

Becker’s (1968) classic paper, ‘Crime and punishment: An economic approach’, attempted to apply theories of rational behaviour and human capital to describe how many resources and how much punishment should be used to enforce different kinds of crime legislation. Much work applying economics to crime has followed, and a full discussion of the market model of crime is provided in Manning and Fleming (in press).

Building on earlier economic models (e.g., Becker, 1968), Farrell and Roman (2000) and Roman and Farrell (2002) provide a conceptual framework for thinking about the effectiveness of crime prevention intervention(s). The model uses the economic concepts of supply and demand and illustrates how changes to these can generate net social benefits. In this context, demand is understood as offender willingness to commit crime at differing levels of risk (or opportunity). Supply is understood to refer to societal willingness to provide opportunities at a given level of risk (reducing risk incurs a financial cost).

In addition to considering supply and demand, Roman and Farrell (2002) draw on the economic concept of surpluses. To illustrate the model, take car theft. Given an overall level of risk associated with this crime, some thieves would steal cars even if the level of risk were higher. As a result, they enjoy a surplus (since less risk is involved in offending than they would be prepared to incur). Likewise, some vehicle manufacturers provide opportunities (less secure vehicles) for which the risk of offending is lower than that which offenders would be prepared to incur. In doing so, they, too, enjoy a surplus. Neither surplus is good for society overall and can result in more crime.

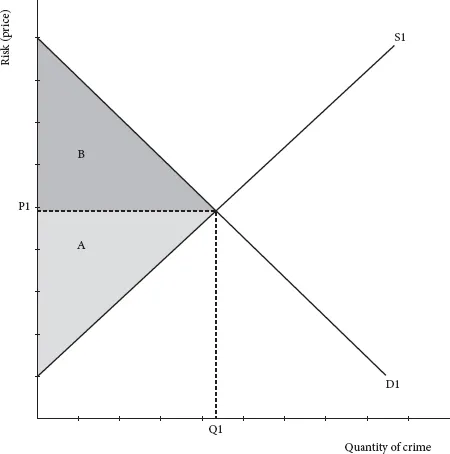

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the supply of criminal opportunities (S1) provided by society and offenders’ demand for criminal opportunities (D1) by offenders in the absence of intervention. For simplicity, S1 and D1 are shown as straight lines, but in reality, they would be curves. The ‘market’ for crime has a scale of risk to the offender (P1) – which is defined by the value at which the risk offenders are willing to incur (along D1) equals the level of risk society is willing to invest to achieve lower crime – and a quantity of crime committed by the offender (Q1). The interaction between S1 and D1 generates victim (A) and offender surpluses (B).

FIGURE 1 The relationship between the supply and demand of crime (and pre-intervention surpluses)

Note: S1: Supply of criminal opportunities (by victims), D1: Demand for criminal opportunities (by offenders), P1: Scale of risk to the offender, Q1: Quantity of crime committed by the offender, A: Victim surplus, and B: Offender surplus.

Source: Roman and Farrell (2002).

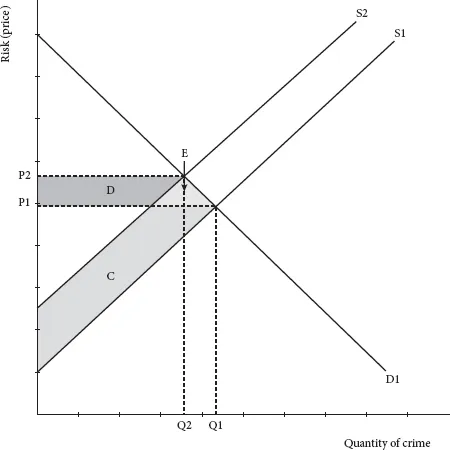

Returning to the car crime example, if policies are introduced that oblige manufacturers to improve their security (see, Webb, 1994) then both the offender and opportunity provider surpluses are reduced. Crime goes down. This concept is demonstrated in Figure 2 as an inward shift in the supply curve (S1 to S2), which represents a reduction in the supply of (lower risk) criminal opportunities, and an increase in risk to the offender (P1 to P2). The result is a reduction in the number of crimes committed (Q1 to Q2). The net gain to society, due to fewer low-security potential targets, is represented by the shaded areas C and E. Potential victims, in this example, have gained, and offenders have lost because the original offenders surplus (shaded area B in Figure 1) has been significantly reduced. A loss in offender surplus is represented by shaded areas D and E – area D is a transfer of offender to victim surplus. Roman and Farrell (2002) state: ‘a net social benefit is produced [in this example] since the additional surpluses from areas C and E are removed. Hence, the crime prevention intervention shown ... produces a net social benefit’ (p. 65).

The efficacy of intervention

The theoretical concept introduced in the previous section demonstrates how crime prevention interventions are able to produce net social benefits. However, an efficacy question – ‘What is worthwhile?’ – remains. This question can only be addressed when the net social benefit/loss (as an output of the intervention) is compared to the various costs of the intervention (including direct and indirect costs).

EA attempts to provide government, businesses and individuals with information to improve choices between alternative crime prevention options. EA is relevant, for example, to debates over the overall financial value of imprisonment (Meyer & Hopkins, 1991), the efficiency of mandatory-sentencing laws (or the ‘three-strike’ law) (Greenwood et al., 1994), and the adoption of programmes such as ‘Scared Straight’ (Petrosino, Turpin-Petrosino, & Finckenauer, 2000).

Understanding the conceptual foundations of EA (CBA in this case) provides the basis for determining when it can be used as a decision-making tool, when it can be used as a component of a broader analysis, and most importantly, when it should be avoided (Boardman et al., 2006). The following sections of this chapter introduce the reader to a number of important concepts including ‘Pareto efficiency’, which provides the conceptual basis for CBA, and potential Pareto efficiency, which provides the practical basis for CBA. An understanding of these concepts will allow the reader to distinguish EA from other analytical frameworks.

FIGURE 2 The relation...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Economic Analysis and Public Policy

- 2 Conceptual Foundation of Economic Analysis (EA)

- 3 EA Techniques

- 4 Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA)

- 5 Extensions to Economic Analysis

- 6 A Scale for Rating Economic Analyses

- 7 The Costing Tool

- References

- Index