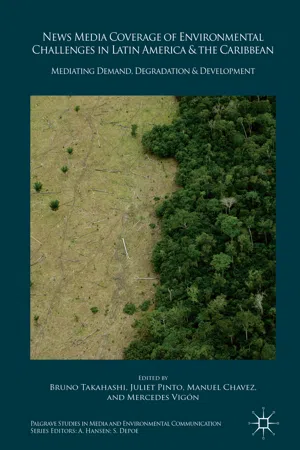

A region home to some of the most important ecosystems in the world—including the Amazon rainforest, Galapagos Islands, Andes mountains, Patagonia, and the reefs, coastlines, and maritime areas of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, among others—Latin America and the Caribbean provides important opportunities for scholarship examining the nexus of economics and environment, politics and populace, and the articulations of the ecological world in the mainstream, legacy media, who serve as much in agenda-setting capacities as they do in reflecting signals from society and institutions. Many of these countries are also uniquely vulnerable to global climate change (CEPAL 2015; World Bank 2014). This includes the melting of the tropical glaciers in the Andean region that serve as the main source of water for millions of habitants; the deforestation of the Amazonian region; acidification and fisheries depletion along the coasts; species extinctions; as well as extreme natural events and disasters, such as El Niño, and the exacerbation of their effects on populations who may already suffer unreliable levels of access to basic services (CEPAL 2015).

Indeed, Latin America and Caribbean countries have faced a multiplicity of structural challenges—political, social, and economic—over the last couple of centuries, all of which have hindered the equality of economic and social development across class and racial cleavages (Skidmore et al. 2013). Social inequalities, cycles of political and economic instability, and the degradation of the natural environment have ensued. Historical legacies from colonialism have in part made most of these countries heavily dependent on their natural resources, oftentimes to the benefit of developed nations—a modern form of dependency (Skidmore et al. 2013). This dependency has led to a variety of environmental problems, including the pollution of waterways, deforestation, and air pollution, among others.

But at the same time, the ecosystems and natural resources found in the Latin America and Caribbean region are unique and of extreme importance to the rest of the world. From abundant fisheries to endemic hardwoods, unparalleled biodiversity, and exotic fruits, among many others, this region continues to offer to the rest of the world not only products and natural resources, but also ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration and purification of water and air which take place in the Amazon (Strassburg et al. 2010).

In addition, many countries in the region play a significant role in global environmental politics. For example, Brazil hosted the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit, and now as an emerging economy and as part of the BRICS bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), has a strong influence in global environmental negotiations. In addition, Argentina, Mexico, and Peru have hosted the UN Conference of the Parties meetings, and Amazonian countries participate in the UN’s REDD+ programs. Furthermore, Bolivia, Venezuela, and to a lesser extent Ecuador, have taken a shared position on climate change negotiations, firmly condemning developed nations for their role in greenhouse gas emissions. In 2008, President Rafael Correa and the Ecuadorian government approved changes to the constitution that granted nature constitutional rights, and a voice, for the first time in history (Becker 2011). Various actors compete for public attention in mediated environmental discourses. The media is a public arena (Hilgartner and Bosk 1988) where claims-makers battle and negotiate over meanings that attempt to socially construct nature as well as environmental problems. These alternative voices can indeed shape local, regional, and global environmental discourses.

By providing case studies of instances of national news coverage of environmental challenges, we hope to further and expand research in a variety of disciplines that critically examine mediated articulations of demand, degradation, and development, and the cultural, political, economic, and societal influences on them. Environmental news coverage provides an important opportunity to take the pulse of how and why news is produced in the region. In Latin America and the Caribbean, such coverage is uniquely important, as many if not most national economies depend heavily on the exploitation and exportation of their natural resources.

Coverage of these processes through a mediated lens provides a scalable analytical view of how local politics meets national political and economic agendas and international capital flows, and national and international journalism production meets established global power structures. Added to this mix are factors such as severe income inequality, indigenous politics and citizen activism, and questions of identity, development, modernity, and legitimacy, as actors at every level battle to dominate and structure the narrative, legitimize the mediated discourse, and decide the voices that will be transmitted along myriad mediated platforms.

The Politics of the Environment in Latin America and the Caribbean

Harnessing national well-being to natural resource exploitation and exportation is not new. At the beginning of the last century, a global commodities boom sent prices for exports skyrocketing, including those for soybeans, wheat, gold, silver, natural fertilizer, oil, and many others. Governments rushed to leverage the boom, with the promise that this ‘resource nationalism’ (Yates and Bakker 2014, p. 15) would fund social development (Gao 2015). After the global economic crash of the Great Depression and World War II, which followed it, such resource nationalism was replaced by populist economic strategies, such as import substitution industrialization (Skidmore et al. 2013) and national interventions in economic development. These strategies mostly failed for those countries that faced a lack of competition and innovation. This in turn generated economic and political instability, which in some cases led to military takeovers of democratic regimes. In the cases of Argentina and Chile, these golpes de estado (coups d’état) meant that thousands of dissidents disappeared and were detained and/or tortured; this state of affairs lasted for a decade, until democratization processes returned.

The rocky transition from military regimes to democratic governments in countries such as Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Brazil, and the high levels of corruption in most countries (Seligson 2002) affect governability, which is reflected in the weakness of the rule of law and the fragility of governmental and nongovernmental institutions. In this context, the environment as a policy issue was institutionalized via ministries in most countries in the region (Takahashi and Meisner 2012), but was always undermined by economic interests tied to extractive industries (Liverman and Vilas 2006). By the turn of the twenty-first century, all that was old was new again. What others termed neopopulist governments had once again capitalized on a global commodity boom to feverishly exploit resources and export them to meet international demand, particularly from the exploding economic giant China (Jenkins et al. 2008). Latin American leaders’ rhetoric joined progressive promises with extractive activities to argue that national development, moving sectors of the populace out of poverty and into ‘modernity,’ depended on exploiting ecological systems . This ‘pink tide’ swept across much of Latin America and was a stark shift away from the neoliberal policies that had accompanied the return to democratization processes in the last decades of the twentieth century (Chodor 2014). Although neither type of regime made particular efforts to conserve environmental integrity, the discourse had shifted to place national concerns over international investment (Grugel and Riggirozzi 2012).

The free-trade policies that emerged during the period from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s were touted as potential regional agreements that included environmental protection measures. In 1994, that was the case of Mexico, which made the creation of policies to protect its natural resources and environment one of the major conditions of the passing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In fact, the agreement included an environmental parallel agreement that focused particular attention on the creation of protected areas in regions shared as borders between the three countries that were involved (Canada, the USA, and Mexico) and in areas of heavy manufacturing and industrialization in each country. Of these three countries, Mexico, having been the weaker environmental regulator, turned into an active international actor to protect the national environments of developing countries (Chavez 2006). The intentions and results of this successful example inspired the planned creation of a Free Trade Area of the...