Abstract

Even though the term “open data” seems to be self-explanatory, it follows clear guidelines and involves an ecosystem of complex domains, including computer science, economics, and legal theory. For the nations of Southeast Asia, open data has great promise, but it also involves particular challenges. Users of open data—governments, civil society, businesses, and academics—should have a clear understanding of the many components that enable open data to reap the benefits of this powerful idea.

Most professionals work with data in some capacity, and Big Data and open data are hot topics; they permeate the business plans of startups, and research universities are weaving these labels into their proposals and projects. Regardless, many underestimate the complexity of data and the ecosystems that surround them, which often ends in frustration when results fail to materialize. At the same time, the fuzziness of the term “open” is susceptible to interpretations that often have ulterior motives. It may describe free markets for some, others understand it as the government’s support for access to public goods, or they may see it in the paradigm of open source and its principles of ownership (Smith et al. 2011).

The Open Definition provides a conceptual framework for open data, defining it as data that are publicly available to anyone for free use, reuse, and redistribution. 1 Open data differs from “public data” that may be available for free download on a website because it comes with an open license that allows commercial and non-commercial use and distribution without limitations. The term has become a popular mainstay in reports about data science and the data revolution, but the concepts of open information sharing have been around for a while. When Francis Bacon mused that “knowledge is power” more than 400 years ago, he might have been the first proponent of today’s open data movement (Bacon 1597). Scholars have examined the self-governing nature of open scientific communities in the 1940s (Merton 1973; Polanyi 1951), and the USA and the European Commission (EC) pushed toward the development of information markets since the 1980s (Janssen 2011). Just as fresh air and sunlight, information should be a public good, one that is non-rivalrous and non-exclusive. However, in comparison to other public goods, information has an additional property: Using and processing it actually enhances this common resource (Hess and Ostrom 2007).

Open data touches several complex topics, including computer science, economics, institutional and organizational theory, political and social science, governance and policymaking, law and legal theory. Because of this complexity, diffuse notions of open data exist. Even though the term seems to be something that most people intuitively comprehend, its serious understanding needs broad knowledge. This book investigates the underlying mechanisms that enable open data and relates them to opportunities, challenges, and risks in Southeast Asia, providing a holistic perspective on the role of open data in the region. It also offers a foundation that future studies may build on to create specific conclusions necessary to drive open data policy and data governance.

1.1 The (Open) Data Revolution

The volume of data in the world is increasing exponentially. IBM estimates that 90 % of data in existence today have their origin in the last two years alone.

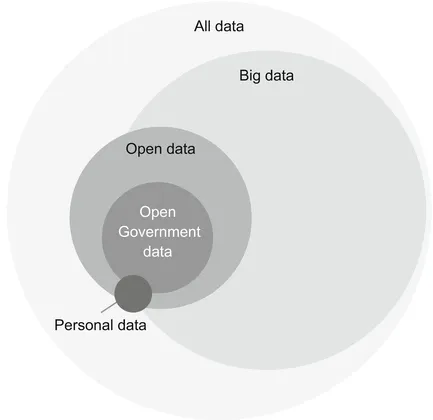

2 Data include much more than statistical indicators: Maps, sensor readings, posts on social networks, pictures, or video also count as data. Open data goes beyond data from the government alone: Non-governmental organizations, universities, companies, or individuals can post open data publicly for people to analyze. Figure

1.1 describes how open data relates to other types of data, including Big Data, Open Government (OG) data, and personal data (McKinsey Global Institute

2013).

Official portals with OG data currently draw most attention in the field, and this book mainly looks at OG data, where government agencies and national statistics offices of countries feed open data portals. In this book, the terms “open data” and “Open Government data” describe the same thing. This book examines two of the main definition frameworks for open data, including the Open Definition and the Open Government Data Principles (Chap. 3). “Open data” in this book implies data that conform to both.

Governments still fail to gather and analyze data on many aspects of people’s lives that would improve their economic prospects and well-being, and supportive ecosystems for the private sector and citizens to use data are often missing. National statistics offices often release data too late or not at all, with inconsistent metadata or at levels of detail too coarse to derive any actionable insight. As a result, the bulk of knowledge in the world still resides in remote databases on computers that their owners choose to keep to themselves. The United Nations’ (UN) Independent Expert Advisory Group (IEAG) notes this lack of data can lead to the denial of basic human rights or to unnecessary delays in coping with environmental degradation (Data Revolution Group 2014).

Governments and their agencies are the biggest collectors of data, including geographic data, statistics, information on the weather, traffic, tourism, and many other domains. Such data are important not only for governments to make decisions and develop policies but also for the private sector and individuals with an interest to create products and services. Especially data with a geospatial reference, such as the location of hospitals, schools, public services, or other information, offer opportunities to improve the livability and sustainability of regions and cities. Opening up these data has the potential to take advantage of advances in information technology to increase the body of collective human knowledge with resources that largely already exist.

1.2 Open Data Process

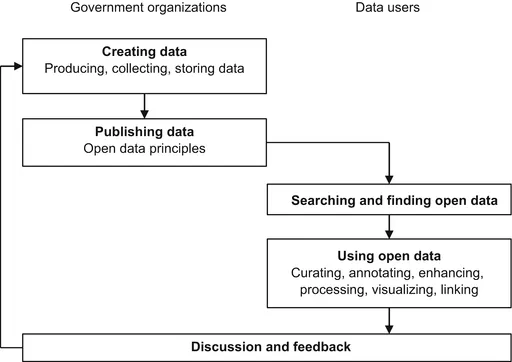

Most open data initiatives follow a basic process consisting of five steps: Creating data, opening data, finding data, using data, and discussing data (Zuiderwijk et al.

2012). Creating and opening data are in the domain of the government, while finding and using data relate to data users. Discussing data and giving feedback involves both governments and data users. Figure

1.2 illustrates this process, which helps identify stakeholders and their potential expectations and reservations. Several barriers and risks apply to different stages of the open data process. Chapter

2 describes some of these barriers, and Chap.

5 examines challenges for open data that exist in Southeast Asia in particular.

1.3 Rationales for Open Data

The most common rationales for the usefulness of open data include:

Economic gains—the creation of economic value through reuse of public sector information in new products and services by the private sector;

Administrative efficiency—greater administrative and organizational efficiency through data sharing in administrations;

Transparency and accountability—of the public sector in general;

Social progress—addressing societal challenges through crowdsourcing for innovative solutions; and

Citizen participation—empowerment for better integration of citizens in political and social life.

Open data has its origins in Western democracies, which often point out the power of openness to strengthen democratic processes. Chapter 2 will examine the promises of open data in more detail. Strong inks and overlaps exist with OG, which Chap. 3 discusses. Best practices for using open data have emerged. These include hackathons and app competitions that bring together software developers to create services or solve specific problems with data analytics (Hielkema and Hongisto 2013; Kuk and Davies 2011). The emergence of data journalism plays another vital part in the use of public data (Gray et al. 2012). Together, these practices form a model in which intermediaries with technical skills use existing data from the government to release their economic and social value (Davies et al. 2013).

1.3.1 “Raw Data Now”

Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web and an outspoken open data advocate, encouraged the audience at a TED conference in 2009 to demand “raw data now” from their governments. 3 In the same year, the governments of the USA and the UK launched the first open data portals, and many countries followed suit. However, after the early days of enthusiasm and bold initiatives to change the world through data, the idea needs to live up to its promises before it can spread as a mature, sustainable, and useful technology on a global scale. This concerns both the supply and management of governments’ open data portals and the demand from businesses, civil society, and citizens. Governments need sound open data strategies and commit to them, which includes more than simply publishing data and waiting for economic gains and knowledge to appear. To make open data work, data users need t...