Geography and Languages

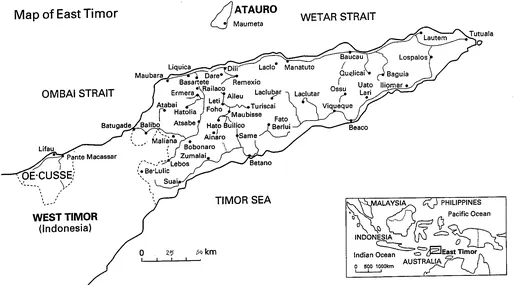

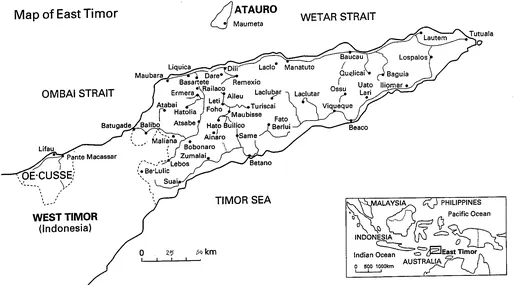

The beauty of Timor Island lies in its blue seashore and discontinuous green central cordillera. This crocodile-shaped island is located at the far eastern end of the Malay World, south-east of the deep Ombai Strait, and includes East Timor and the Indonesian West Timor. For a view of East Timor in the 1970s see Chrystello. 2 East Timor, or Timor-Leste, encompasses 19,000 square kilometres and a population of 1.3 million in 2016. Lying north of Darwin, Australia , East Timor is a part of Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. It has an enclave called Oecussi, Oecusse or Ambeno (“oe” means “water” in Meto, the language of the local Atoni people, see Map 1.1 above). Its main city is Pante Makassar (Macassar).

According to James Fox, East Timor is remarkably diverse “in its linguistic and ethnic make-up.” 3 East Timor, a country in Southeast Asia, is also related to the Pacific Ocean and Austronesian cultures. However, Portuguese colonization had a great impact on East Timor’s linguistic history. Around 40% of the Tetum-Praça words used in Dili , the capital, are Portuguese, but the grammar of the national language is Central Malayo-Polynesian. Local newspapers are printed in Tetum and Portuguese. Both are official languages , but Portuguese remains the major language of the Republic. The Constitution was first drafted in Portuguese. The colonial period, which promoted the usage of Tetum, in particular in Dili , also pushed the more literary Portuguese language . The issue of language remains problematic in 2017. The cultural and political Timorese elites are educated in Portuguese, and there is a great cultural gap between them and the youth who have been educated in the Indonesian language (Bahasa Indonesia ) for 24 years. 4 Tetum has the advantage of being the liturgical medium of the East Timorese Catholic Church. Unfortunately, the Bible has not yet been properly translated into Tetum, although more than 90 percent of the East Timorese are Catholic. Nevertheless, Pieter Middelkoop (1895–1973) had translated the Bible into Meto, which is still used among the Atoni of East Timor, Kupang , and Kefamenanu, West Timor, and Indonesia. 5 Although Portuguese is the main language of the Timorese laws, the English language deserves a better consideration in the Constitution of East Timor. Australia is a close neighbor and its education system could be very useful for East Timor, but there are few competent English teachers in East Timor. The official languages are Tetum and Portuguese. The country’s Constitution states that Indonesian and English remain working languages .

Timor has 14 different Austronesian languages and many of them are mutually unintelligible. 6 They were all part of the local culture of former chiefdoms. To understand the complex customary system of the island, it is necessary to briefly classify the languages of Timor. 7 These 14 languages are spoken in different Timorese districts as follows: Tetum is spoken in Dili , Batugade, Suai , and Viqueque; Adabe in Atauro Island; Mambai is used in Samé, Aileu , and Ainaro ; Fataluco is spoken by the Dagada people in Lautem and Los Palos; Meto or Vaikenu dominates in Oecussi; Tokodede is spoken in Liquiçá and Maubara; Makasai in Baucau and Baguia 8 ; Galole in Manatuto ; Bunak in Bobonaro; Kemak or Emak in Kailaku; Idate in Laclubar; Lakalei in Samé; Kairui and Midiki in Lacluta and Viqueque; Nauete and Naumik in Uato Lari. In 2000, instead of using Indonesian interpreters, the UNTAET used Tetum interpreters, meaning they were sometimes unable to communicate with Timorese people in some districts. For example, they were unable to communicate with Fataluco speakers in the eastern district of Los Palos. Between 2000 and 2002, it was not politically correct to use Bahasa Indonesia , despite it being commonly spoken after 24 years of Indonesia rule. However, in Oecussi the local people, Atoni, speak Meto or Vaikenu; Tetum was often not favored, except for the elite who’d been educated in Dili or later for those who had a job in the capital. The family of the traditional chief, liurai João Hermenegildo da Costa in Oecussi, avoided using the Indonesian language. This particular liurai —fluent in Meto and educated in Portuguese—always preferred to use an Indonesian interpreter knowing also Portuguese or Meto. Compared to the first decade of the 2000s, the enclave is recently more “Indonesian-influenced”, partly because of its geographical proximity to Indonesia. In 2017, Meto, Tetum, and Indonesian are the most spoken languages ; without Indonesian workers and machines, it was not possible to finish the roundabouts and roads in Pante Makassar for the ceremony of the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the Portuguese.

The Portuguese language too cannot be forgotten. It is useful to note the publications of the administrator Correia and his knowledge of the Makasai culture in Baucau . 9 Portuguese colonialism has been criticized for the years 1974–1975. 500 years of Portuguese presence in the country have to be seriously considered, as these have had a profound impact on modern East Timor. In Oecussi, in November 2015, the 500 year anniversary of the arrival of the Portuguese was a reminder of the importance of Timor’s Portuguese heritage.

Portuguese Colonization

First Indian, then Arab and Chinese traders bought sandalwood originating from Timor around the year 1000 A.D. The era of Portuguese colonialism begins in 1515. Initially, Portuguese trading was centred in Lifau, on the coast of Oecussi, and over several centuries Portuguese Timor became economically linked to Goa and Portugal. Sandalwood, and later coffee, were the main Timorese colonial exports, but these natural resources were never as valuable as the silk trade of Macao . As trade grew, and the harbor on the Pearl River Delta expanded, Timor was, for a short period of time, brought under the jurisdiction of the Portuguese governor of Macao. The key administrative turning point was in 1769, when the Portuguese established a real capital and a local colonial governor in Dili . Exactly a century later, Alfred R. Wallace in The Malay Archipelago, gave a relatively dismal image of the capital.

As a colony, Timor was located at the extreme end of the Portuguese Empire. The Governor of Macao and Timor (1879–1883), Joaquim José da Graça, rightly wrote in 1882 that “the number of military cadres” (oficiais do quadro) was insufficient to govern the colony. 10 Governor Eduardo Augusto Marques, after his arrival in Timor in 1908, issued a significant note, numbered 177 in the Boletim Official, and many reports of Portuguese officers followed, using the concept of “indigenous customary law.” This often meant “local justice”, but to cool down reports, the note “no crime” often appeared. Indigenous problems were nevertheless often solved according to traditional rules. During this period of slow transformation for the colony, Governor Marques explained that the Timorese needed a more direct system of colonization, noting with bias reflecting his favorable views of colonialism that the Timorese could not benefit f...